In a city like New York, green spaces and public parks are seen as places to disconnect from the fast pace of urban life. But many of them also have a hidden side—serving as living memorials and final resting places, some dating as far back as the Revolutionary War.

Amelia Medved, a 2023 Fordham graduate, analyzed how the dead have become part of the landscape of the city in “A Breathing Place: Sanctified Burial Sites in New York City Public Space,” a research project she conducted through a Duffy Fellowship from Fordham’s Center on Religion and Culture.

Medved, a studio assistant at the landscape architecture firm SCAPE, says that honoring the collective memory of the deceased is a healthy expression of urban life—one that can “enliven our connection to place and engage the dynamic communities that inhabit New York City today.”

Hart Island

Hart Island, located at the western end of Long Island Sound in the Bronx, has a long and morbidly fascinating history as New York City’s public cemetery, with mass graves stretching back to the Civil War. Described by Medved as a “remote, windy, indeterminate landscape far from the beating heart of the city,” the island had been controlled for many years by the city’s Department of Correction, which used prison labor to bury more than 1 million unclaimed and unidentified New Yorkers.

The maintenance of the island came under scrutiny in 2012, when Hurricane Sandy unearthed some remains. In July of 2015, the grave sites became accessible to the families of those buried on the island, and in 2019, control of the island was transferred to the New York City Department of Parks.

Hart Island is now open to the public through small guided tours requiring lottery registration. The Hart Island Project, a public charity incorporated in 2011, has worked to destigmatize the burial ground and create an online resource to help families find the locations of their buried loved ones.

The Enslaved African and Kingsbridge Burial Grounds, Van Cortlandt Park

Consecrated in 2021, this section of Van Cortlandt Park in the Bronx was nothing more than a neighborhood ghost story until a chance encounter by Kingsbridge resident Nick Dembowski. After noticing a few broken headstones against a fence, Dembowski went to the Kingsbridge Historical Society. There he learned that the fenced-off area was once home to an 18th-century burial ground, particularly for people enslaved at the estate. Their bones were discovered in the late 1870s, when the New York Northern Railroad Company broke ground in the area.

Following Dembowski’s efforts, the Enslaved People Project was born—launched by the Van Cortlandt Park Alliance, Van Cortlandt House Museum, and Kingsbridge Historical society to help shed light on the history of the burial grounds.

Medved said this site offers visitors “the chance to encounter the people who walked through the trees or stood beside the lake centuries ago.”

Prison Ship Martyrs Monument, Fort Greene Park

Just a few blocks from Flatbush Avenue and Fulton Street in Brooklyn, Fort Greene Park is a 30-acre public space, filled with history dating back to the Revolutionary War. In the center sits the Prison Ship Martyrs Monument, a war memorial dedicated to more than 11,500 American prisoners of war. Many of these prisoners, who died on British prison ships in the Brooklyn Navy Yard, were thrown into the bay or buried in shallow graves on the shoreline.

Their remains were left there until the 19th century, when they were collected after funding was secured for a public monument. They were briefly interred in a public tomb before being moved permanently to the newly constructed Fort Greene Park in 1873. The monument that stands today, with its massive doric column and granite stairway, was completed in 1908.

Perhaps the most notable aspect of the monument, according to Medved, is the way it “convenes the living and dead in intimate proximity to the unawareness of most visitors.”

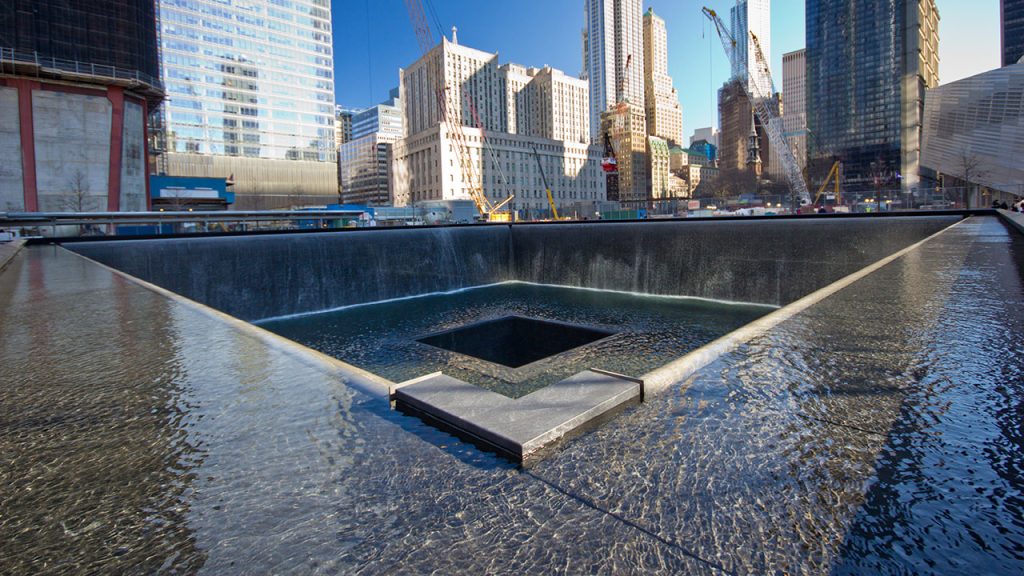

The 9/11 Memorial

Located where the Twin Towers once stood, the National September 11 Memorial & Museum honors the lives lost at the World Trade Center during the terrorist attack on September 11, 2001. The site features two reflecting pools bordered by bronze parapets engraved with the names of 2,983 people—2,977 who were killed on 9/11, and six killed in the 1993 World Trade Center bombing.

The most striking part of the memorial, according to Medved, is the sound—the white noise generated by running water creates a pocket of “overwhelming silence” in an area bustling with foot traffic.

The contemplative nature of the space has led to myriad improvised displays, including “missing” posters, flowers, American flags, rosaries, and even unauthorized etchings of additional names on the monument’s surface.

Medved says that these contributions from visitors are evidence of a vital, dynamic “public grieving process.”

RELATED STORY: How a Passion for the Environment and Visual Arts Led to a Career in Landscape Architecture