Ryan Duns, S.J., is a man of many talents. He’s a scholar of metaphysics with a master’s degree from Fordham. A Catholic priest who chairs the theology department at Marquette. And a master player of the Irish tin whistle with a global following on YouTube.

He’s also really into scary movies.

“I was magnetically drawn to horror films” as a kid, he writes in Theology of Horror: The Hidden Depths of Popular Films (Notre Dame Press, 2024), a book that grew out of a popular course he teaches at Marquette. If we look beyond the gore, Father Duns argues, we just might get as much grist for spiritual reflection from Freddy, Jason, and Michael Myers as we do from Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John.

Fordham Magazine caught up with the 2009 grad before Halloween to discuss the book and get a few movie recommendations that might help us see these dark stories in a new light.

Do you get a lot of weird looks when you tell people this is what you’re working on?

People freak out. They’re like, “You’re a Catholic priest! Aren’t you turning students into demon worshipers and ax murderers!” Well, no, not really. I try to take an unorthodox route to get to some pretty orthodox positions. And as a Christian, I think we have to have our eyes open to the worst humanity can do. I don’t think it does anyone any service to ignore our potency for evil.

Implicit in your work is the idea that these grisly movies have value to society as works of art and culture. Why do you think that is?

In order to appreciate horror, I think you need a very sophisticated worldview. Every week, Christians around the world will profess the Nicene Creed: We believe in “things visible and invisible.” In many of the more popular films—like It, The Conjuring, Insidious, all the exorcism movies that seem to proliferate—there is a sense among viewers that there is an unseen order that is no less real than what we can see.

What horror gives us is a way of probing the dark corners of reality as we understand it. These horror movies do a really good job of helping us to recognize and reflect on the dark side of human nature. There is something we are drawn and attracted to: the transgressive, the dark, the shadow.

How about a lightning round?

Sure.

You noted some favorites in the book—I’ll give a movie, and you tell me your bite-size philosophical takeaway.

Okay!

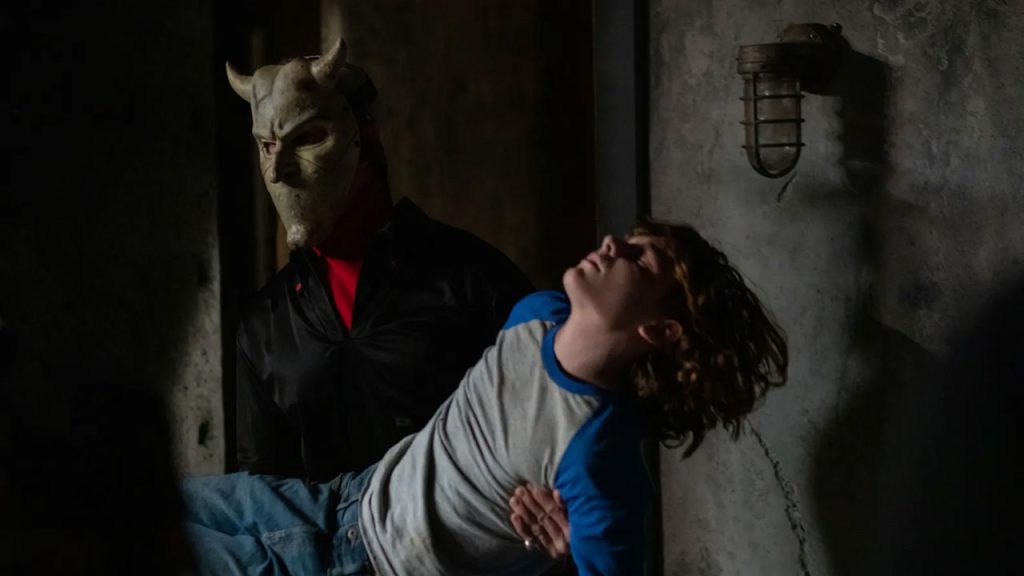

The Black Phone (2021)

A shy but clever 13-year-old boy is abducted by a sadistic killer and trapped in a basement where he hears the voices of the killer’s previous victims.

Oftentimes we only recognize providence, or divine assistance, in hindsight.

The Exorcism of Emily Rose (2005)

A defense lawyer takes on the case of a priest charged with negligent homicide after performing a deadly exorcism on a young woman.

The same reality can be looked at and interpreted in two very different ways. It’s not what we see but how we see.

Candyman (1992)

A murderous soul with a hook for a hand is accidentally summoned to reality by a skeptical grad student researching the monster’s myth.

The sins of the past can be repeated, and those actions reverberate through history.

One theme that threads through all the movies you analyze is this idea of materiality and the relationship between body and soul. Why did you feel that was important?

In Christianity today, there’s a lot of Gnosticism—the idea of a human body and then a soul that controls it like a puppet. Where people go wrong is they think that, “Oh, well, there are things just of the body, and I need only to worry about my spirit.” The Christian tradition says that is not true. Our bodies matter, and I think horror foregrounds the importance of our being incarnate.

And I’ll tell you this—if Leatherface broke into your apartment right now and came at you with a chainsaw, you sure wouldn’t say, “Well, I’m not worried about my body, because my soul will live on.” Hell, no!

Does this mean you’re totally unfazed by gore?

I don’t like things like breaking teeth. I don’t like fingers being crunched or cut off. The body horror stuff does get to me. But they’re vivid reminders of our mortality. I think sometimes a good horror movie forces us to look at things we’d rather look past.

You note that part of what draws you to write about these movies is that you know your students are watching them. How are they reacting to the book?

I get a lot of students who tell me, “I thought this would be an easy class because it was about horror movies, and I can’t believe how much I learned.” Someone else said, “I didn’t know that I could come to believe in God thanks to horror movies.”

This interview has been edited and condensed.