When Hilary Jacobs Hendel reflects on a lifetime of learning, one lesson jumps out. It centers on emotions—how they show up, why we tamp them down, what that suppression can do to us and others.

“A light bulb went off, and it moves me to tears still to think about it,” says Hendel ’04 MSW. “My mind was reorganized in that moment.”

A psychotherapist, author, teacher, parent, and sought-after speaker, Hendel is a crusader for emotions education. Now, with a new book, Parents Have Feelings, Too: A Guide to Navigating Your Emotions So You and Your Family Can Thrive, she and co-author Juli Fraga bring priceless insights directly to the aid of families.

Hendel was just out of Fordham when she attended a conference featuring psychologist Diana Fosha, developer of a form of therapy that helps people process emotions and build on their personal strengths and supports. An illustration Fosha shared that day changed Hendel forever.

In that presentation about AEDP (originally referred to as Accelerated Experiential Dynamic Psychotherapy and now known by its acronym), Fosha shared the Triangle of Experience, a tool she had adapted from earlier researchers’ work. The illustration led Hendel to an epiphany: She had been blocking some of her core emotions, leading to anxiety, overwork, and two major clinical depressions.

By the time she attended that conference in 2004, Hendel was a few years past a decision to change careers, a choice that brought her to Fordham for a master’s degree in social work. She already had earned a bachelor’s in biochemistry from Wesleyan and a dentistry degree from Columbia, and had worked—unhappily—as a dentist. Fordham was her path to the role of therapist that she’d long wanted but hadn’t had the confidence to pursue.

“I really was floundering for many years,” she says. “My friend Heidi Frieze said she was going back to school for social work, and she was going to Fordham. We were both kind of figuring it out at the same time, and we thought Fordham would be the best place for us.”

They were right, says Hendel, then 39. The Graduate School of Social Service offered the flexibility she needed as a single mother of two, and she admired how faculty urged students to build on the strengths of the people they were learning to help. After graduation, she and Frieze ’04 MSW stayed on parallel tracks, attending that mind-opening conference and practicing AEDP.

The Change Triangle: A Tool to Help Each of Us Dig Deep

Today, Hendel is widely known for her evolution of Fosha’s impactful triangle. Drawing on her strong foundation in science, her study of therapeutic modalities, and her personal experiences, she introduced the Change Triangle in 2016. And she has been working to promote it ever since, authoring two books, creating curricula for therapists, and offering hundreds of videos and blog posts to reach the general public.

“The Change Triangle is a tool that is universally applicable to all humans,” she says. “Basically, it just explains how emotions work in the mind and body to cause both distress and symptoms of mental unwellness, and it offers a map to ease and even heal those symptoms.”

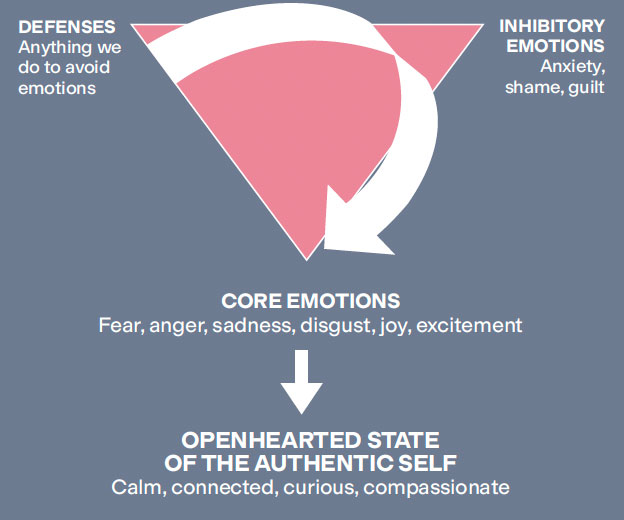

While simple to the eye, the Change Triangle can yield deep self-knowledge and a positive path forward. At the left corner of the upside-down triangle are defenses, things we do to avoid feeling certain emotions. Overworking, drinking, and yelling are among myriad examples. At the right corner are anxiety, shame, and guilt, which inhibit us from feeling the core emotions situated at the bottom of the triangle: fear, anger, sadness, disgust, joy, and excitement.

Hendel says if we can let go of our defenses, recognize our inhibitory emotions, and process our core emotions, we can move to an openhearted state where we are calm, connected, curious, and compassionate. The key is listening to our bodies.

“Emotions are all physical,” Hendel explains. “Core emotions happen in the middle of the brain, then go down through the vagus nerve to activate the body. They’re meant to be used as data. If something is scary, I need my fear to make me run. If something is pleasing, I need my excitement to draw me in, to help me learn. If I lose something, my sadness helps me grieve. And it also helps me love, because if I didn’t feel sad about a loss, I wouldn’t care about the connection.”

RELATED STORY: How to Work the Change Triangle: A Map to Emotional Well-Being

Hendel believes emotions education would have been an even more powerful force in her life had she discovered its lessons earlier. These days, many school districts are offering such coursework, often referred to as social and emotional learning, making it all the more important for parents to know and put emotion-savvy insights into practice.

The stakes are high, Hendel stresses: “What I’m championing is emotions education as a novel and vital public health initiative. From mental health crises in schools to burnout in adults, we’re witnessing the downstream effects of a culture that lacks basic emotional literacy.”

How to Survive Your Teen’s Snark

When you surprise your daughter with tickets for the musical Wicked, she rolls her eyes and walks away. “Whatever,” she says. “That show is lame.”

You feel heat rise in your body, tension in your jaw. “You’re so ungrateful!” you want to yell. But you pause, breathe, and feel your jaw relax.

Raising teens is hard, you think, and you sit with the sadness you feel. Soon you’re ready to start a conversation with compassion for both of you.

“If you don’t want to see Wicked, I can go with a friend. I know it’s not always fun to hang out with your mom.” She feels seen. “Thanks, Mom,” she says. “Let’s do something else instead.”

—Adapted from Parents Have Feelings, Too by Hilary Jacobs Hendel and Juli Fraga

Master Your Feelings, Then Guide Your Kids

Relationships between parents and children can be strengthened immeasurably with greater understanding of emotions, say Hendel and Fraga, a psychologist, parent educator, and mother. Their aim is to show parents how to identify and process their emotions so they can better guide and respond to their kids.

For many, it’s new territory, especially those from families that didn’t address or work through emotions. Hendel uses her own family as an example. For all her wonderful qualities, Hendel’s mom didn’t hold space for sadness.

“She was a wonderful mother. She was patient, calm, curious. But sadness felt too vulnerable to her,” Hendel says. “So, for example, when my dog died when I was 11, her MO was to cheer me up. Had she named and normalized my sadness, I might have felt it was OK to be sad, that the feeling needed time to resolve. Instead, until I discovered the Change Triangle, my anxiety skyrocketed when I or others around me faced losses like the death of a loved one.”

Hendel says it’s important for parents to help children identify their core emotions and validate them.

“If, as parents, we’re OK with our feelings, we’re going to be much more OK allowing our children to feel what they feel. And as a result of being raised in a home where emotions are expressed and validated, children will grow up being able to validate their own emotions and can pass that gift down to their children. The ultimate effects are going to be less anxiety, less depression, and more self-confidence.”

How Not to Scream Over Spilled Milk

Your “little scientist” turns over his cereal bowl at breakfast. You shout “No!” and, clearly irritated, rush for paper towels. Frightened by your reaction, your son doesn’t recognize what he is feeling. It’s anxiety, but he might think something is wrong with him.

With greater self-awareness, you could have kept your calm and said, “Well, look who just discovered gravity! Now it’s time to clean up. Let’s do it together.” Your child would have remained relaxed and happy, and you would have laid the groundwork for him to know he can make a mistake without jeopardizing his connection with you.

—Adapted from Parents Have Feelings, Too by Hilary Jacobs Hendel and Juli Fraga

Hendel’s advocacy for an emotion-informed approach to parenting is inspiring to Natasha Prenn ’04 MSW. The two met during a grad school field placement, and Prenn has long had a front-row seat to Hendel’s growing recognition as a therapist and author.

In 2015, a column by Hendel emphasizing the critical role parents’ emotional attachment plays in their children’s psychological development was accelerating to become the day’s most-emailed New York Times article, and Prenn rushed to Hendel’s side.

“She was home alone, and she was completely overwhelmed. I was like, ‘I’m coming! I’m coming!’” says Prenn, who lived near Hendel on Manhattan’s Upper West Side. “It’s been a very exciting ride to watch her work so tirelessly to help people.”

Benjamin Lipton, a senior and founding faculty member of the AEDP Institute, recalls Hendel’s enthusiasm about that type of psychotherapy and admires how she’s taken its tenets to general audiences.

“The way the human brain has strived to deal with overwhelming experiences is to say, ‘I’m going to cut those off. I’m going to tuck those away. I’m going to block that out. I’m going to pretend that never happened. I’m not going to deal with that,’” Lipton observes. “And we can only do that so long before we start to pay the price for it, which is the reason we have the kinds of problems we’re seeing today—epidemics of violence, an inability to communicate constructively with people we disagree with, problems with parenting, difficulty maintaining long-term relationships, you name it.”

Helping parents understand their emotions and deal with their own traumatic experiences is vital in interrupting cycles that are unhealthy and, in some cases, dangerous, Lipton says. Without it, the harm just gets perpetuated in the next generation.

“What Hilary is doing is so important, because it has an opportunity to really change the course of things. The more people get educated, the more the world really changes, one person at a time,” he says. “And parents literally are the creators of the next generation. It’s not just metaphorical, it’s literal.”

After that Times column appeared in 2015, two literary agents reached out to Hendel, leading to her first book, It’s Not Always Depression: How to Work the Change Triangle to Listen to Your Body, Discover Core Emotions, and Connect to Your Authentic Self. Then, having already co-written articles for The New York Times, Slate, and Time magazine, Hendel and Fraga decided to team up to help today’s parents and, trusting in the domino effect, hopefully generations to come.

“Emotions education is the bread and butter of family wellness,” Fraga says. “These are skills that last a lifetime.” And perhaps longer.

—Mary Alice Casey is a Fordham Magazine contributing editor.