Just as the Sept. 11 attacks showed that government agencies must work together to prevent terrorism, today’s cyberthreats show the need for a different kind of cooperation—between the government and private companies, former FBI director Robert Mueller said on Jan. 8 at Fordham.

The government has information that companies can use to protect themselves from online threats, Mueller said on Day 3 of the International Conference on Cybersecurity (ICCS2015) co-hosted by Fordham and the FBI.

“We have a long ways to go in breaking down the barriers between the federal sector on the one hand and the private sector on the other, but any success we have in the future will be dependent on breaking down those barriers,” he said.

He recalled hard lessons learned in the wake of the terror attacks. Before Sept. 11, he said, “FBI did not speak to CIA, CIA did not speak to FBI, and neither of us spoke to anybody else, and the fact of the matter is, for us to develop any success in addressing counterterrorism we had to speak to each other.”

Partnerships among federal, state and local government agencies “were absolutely essential to any success we had in thwarting attacks,” he said.

Another lesson from his time as FBI director is the importance of having—and regularly meeting with—a chief information security officer who’s capable and has a prominent place in the organization.

Also important is having the right corporate structure, in part because cyberthreats can come from both without and within an organization. “We underrate the insider threat and the necessity for bringing in human resources when you’re preparing to prevent cyber attacks,” he said.

He emphasized the need to figure out ahead of time who will handle various tasks such as investigating a cyberattack, explaining it to board members and shareholders, and handling the media (including social media).

“What you see time and time again is the lack of preparation and the waste of valuable time in that critical period in the wake of the breach,” he said. “Inevitably, if there have not been preparations, one does not know at the outset who is in charge.”

He was immediately followed by another presenter who called for more forward-looking measures such as new computer hardware that’s more secure than the “leaky” systems in use today.

“We need to have customers say they want this, put some pressure on the hardware vendors,” said the speaker, Ruby Lee, Ph.D., the Forrest G. Hamrick Professor of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science at Princeton University.

“Cyberattackers are very smart people,” she said. “They know every trick that we as cyberdefenders know, and probably know it better. Every attack we know of, they probably already know. Every defense we know of, they probably also know.”

“We need to anticipate their moves,” she said. “We need to plan ahead.”

-Chris Gosier

Distinguished Panel

Experts Say Cyberthreat Not Unlike Bomb Threat

“Why is it not enough for the FBI director to say it’s them?” said Preet Bharara, U.S. District attorney for the Southern District of New York, referring to public doubts that North Korea is responsible for a state-sponsored cyber attack against Sony.

Bharara moderated a panel on Day 3 of ICCS 2015 in which members called the Sony attack a “game changer” in U.S. cyberattack responses. A day earlier, FBI Director James Comey had announced new evidence that the North Koreans were “definitively” responsible.

Lisa Monaco, assistant to the president for Homeland Security and Counterterrorism, said that most of the people doubting the assertion lacked the sensitive information that intelligence community holds.

“Given the potential for ramifications, the decision to release this information is not taken lightly,” said Manaco. “So to have doubt cast on the FBI can be counterproductive.”

Former Michigan congressman Michael J. Rogers, who chaired the House Intelligence Committee, said that his office was one of the first to publicly point a finger to a nation-state when it accused China of cyber attacks four years ago.

“At the time it was earth-shattering,” he said. But publicly calling them out lets the public know that the government is taking steps. He said that the process of identifying the perpetrators remains important even if the accused are not extradited.

“We’re the FBI, we’ll wait for them for 30 years,” said panelist Joseph Demarest, assistant director of the FBI’s cyber division.

Another reason to make attributions public is to make the private sector aware of the very real threat, said Rogers. Unfortunately, the public’s curiosity about the Sony hacking extended to gossipy emails and nude photos of actors; if a bomb had done the same damage to Sony’s data there would’ve been a very different reaction, he said.

Each of the respondents treaded carefully to Bharara’s question as to whether the Sony attack constituted an “act of war.”

“If you want to go punch your neighbor, you’d better hit the weight room first,” said Rogers, who faulted some of the private sector for too much swagger and not enough substance. “If you declare an act of war, the people who will get hurt the most won’t be the government or military, it’ll be private sector businesses—and our private sector is just not ready.”

Monaco suggested that while a bomb could kill innocent bystanders, the threat to life might be no less significant in a cyber attack.

“If that same type of activity was leveled against critical infrastructure, you can easily spin out that scenario,” she said. “The vast majority of our nation’s infrastructure is riding on privately owned networks.”

She added that the Sony case has proved that public-private partnerships will be critical to get ahead of the problem.

“The very real duty of the next congress will be an information-sharing bill,” she said.

Rogers sponsored the yet-to-be-passed Cyber Intelligence Sharing Protection Act, which aims to defend corporations from cyber attacks by foreign governments. But the bill has raised privacy and civil liberty concerns. He said that democratic debate might limit a coordinated approach.

“There’s capability [of cyber criminals]out there that ought to scare the bejesus out of everyone in this room, on Wall Street, and on Main Street,” he said. “But we are behind in making the public aware. We are a representative republic and if they’re not with us it’s not going to work.”

-Tom Stoelker

Taking Down Malware

Game Over for Gameover Zeus?

It’s not surprising that the malware Gameover Zeus(GOZ) is named after a God.

Famous worldwide for being omnipresent and seemingly omnipotent, the credential-stealing program proved so resilient that the normal template for taking down such threats was useless, said Ethan Arenson, a prosecutor for the U.S. Department of Justices’ Computer Crime and Intellectual Property Section’s criminal division, speaking at ICCS2015.

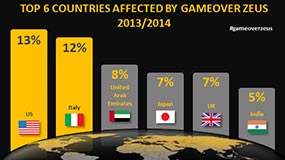

GOZ and other botnet programs form networks of “zombie” computers, infected without their owner’s knowledge. A rather exclusive, virulent variant of the old Zeus bank credential-stealing malware, GOZ had infected between 500,000 and a million computers internationally by 2014 and drained more than $64 million, mostly by robbing the bank accounts of small and mid-sized businesses, Arenson said.

“That’s where they got the biggest bang for the buck,” he said of the perpetrators of GOZ. “They could take hundreds of thousands, even millions, of dollars at a time as opposed to dealing with residential accounts.

“You log in to your bank, expect to see your account balance, and it will say ‘Something is wrong [with the server], please log back in in 30 minutes.’ During that 30 minutes, your money is being stolen.”

The program was tough to take down because it had three separate operating layers in which to penetrate—a peer-to-peer framework, many proxy nodes, and an algorithm that generated 1,000 domain names weekly. If one layer was penetrated, the system’s network could heal itself much in the same way that a worm will grow back its decapitated head.

“We called it the three-headed monster,” said Arenson. “And the only way to take GOZ down was to take all three heads off at the same time.”

That is exactly what the DOJ did, with help from the FBI, other nations, and several private companies. The team discovered ledgers of the addresses of the financial transactions, which it matched to the victims. It also discovered GOZ’s technical issues site, and collected information on staff members, including their IP addresses. (The name of the main perpetrator was Evgeniy M. Bogachev.) The FBI then set up a “sinkhole” computer and got a court order allowing them to redirect the GOZ’s domains back to that computer.

They were able to eventually indict Bogachev in 2014—on paper, at least.

The team is also working with private industries to offer the GOZ victims free software that will clean their machines and networks.

As for Mr. Bogachev, who is likely somewhere in Russia, the team asked for assistance from the Russian government in extraditing him to stand trial. So far they have not heard back.

“We are standing by,” said Arenson.

Admiral Michael Rogers: NSA Director Offers Chilling Forecast for Cybersecurity

When asked to predict the state of U.S. cybersecurity in five years, National Security Agency Director Admiral Michael S. Rogers admitted that he was worried.

Despite our increasingly advanced technology and growing savvy in the cyberworld, “the trends are going in the wrong direction” when it comes to security, Rogers said at the Jan. 8 conclusion of ICCS2015.

“What worries me is that things are going to get much more destructive,” said Rogers, who is also the commander of the U.S. Cyber Command. “To date, the destructive acts directed against U.S. infrastructure have been relatively limited… But if we don’t change the dynamic, then in five years this is only going to increase.”

Rogers said that the rising threat of cyber warfare calls for a new strategy—one that will deter terrorists and hostile nation-states from engaging in cyberattacks, rather than one that is purely defensive. To do this, the United States needs to make clear to hackers and terrorists that either they will not be successful in their attempts at cybercrime, or they will pay so steep a price that even a successful attack isn’t worth the consequence.

The time to send this message is now, Rogers said, especially in light of the recent attack on Sony.

“The entire world is watching how we respond,” he said. “If we don’t acknowledge this situation and name names, then it will encourage others and [imply that]this isn’t a red line for the U.S. And that can’t be further from reality. It’s absolutely unacceptable and we need to communicate that to the world.”

In the meantime, the country also needs address pervasive trust issues internally. Rogers conceded that tactics such as the NSA’s use of big data analytics have caused deep concerns about privacy and have sullied alliances among government, the private sector, civilians, and other constituents. That said, that these methods are neither new nor unique.

“If you think the use of big data to understand personal behavior is a phenomenon [limited to]intelligence, I would asked you, ‘What world have you been living in for the past 15 years?’ Big data is foundational in the business sector as well as the world I live in,” he said.

“In the end, it’s about striking a balance between the safety and the rights of our citizens…We need to have a broader dialogue as a nation about what privacy means to us in the digital age and what we are comfortable with as a nation.”

Reconciling concerns about safety and privacy is especially important now that there is no longer a difference between the communication infrastructures used by hostile nation-states and terrorists and those used by the average citizen—which makes surveillance more complicated.

“Sydney, Ottawa, London, Madrid, Washington D.C., Shanksville, New York City, and very likely now Paris—in every single one of these instances, there was some measure of coordination [among actors]using the exact same communication paths, the exact same software, and the exact same social media platforms that the rest of use,” he said.

Cognitive Computer Watson Designs Cocktail for ICCS Reception

On the final day of the 2015 International Conference on Cyber Security (ICCS), the farewell party featured a “smart” computer serving up drinks.

Watson, a cognitive technology developed by IBM, created a signature cocktail for the evening by gathering information from 9000 recipes from Bon Appetit and “learning” from that information. Watson was able to process the language from the recipes in order to hypothesize which ingredients, when combined, would make for a tasty and completely original drink.

The “Watson”, as the drink was named, contains a carefully calculated mixture of congnac, champagne, honey, ginger, banana nectar, apple juice, orange juice, and lemon juice.

-Rachel Roman