If you cannot recognize profound injustice around you, you cannot act upon it.

That, said Bryan Massingale, S.T.D., is why white American Christians allowed their black brethren to be subjected to decades of race-based terror that drove six million of them to flee their homes in the South. It is also why today’s racial problems are dismissed by many white Christians as having no connection to that past.

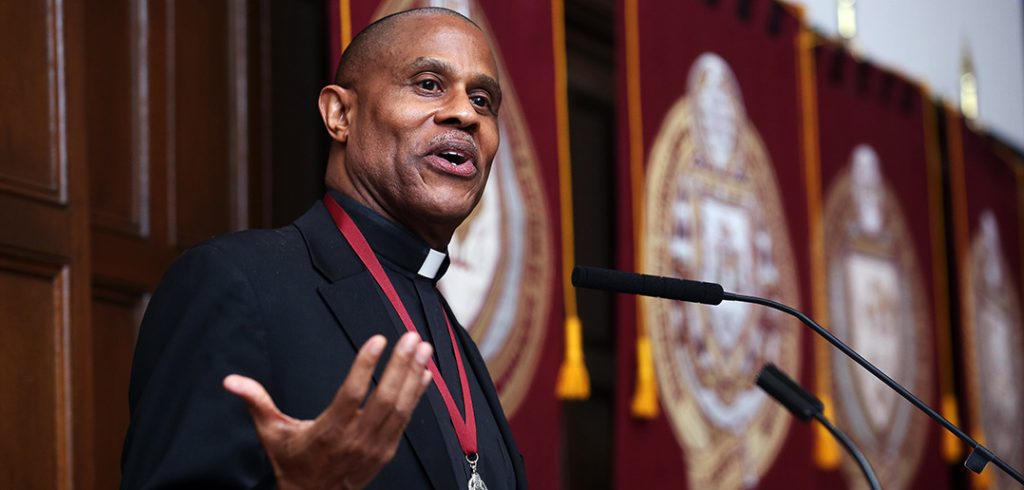

“Systemic, collective insensitivity and unawareness is the most theologically involved problem at the core of Christianity’s collusion with white supremacy,” said Father Massingale, who was installed as Fordham’s James and Nancy Buckman Chair in Applied Ethics on Feb. 27.

“How could so many well-meaning and well-educated people be unaware of the racial terrors that unfolded and still unfold around them?”

In his lecture, “They Do Not Know It and Do Not Want to Know It: Racial Ignorance, James Baldwin, and the Authenticity of Christian Ethics,” Father Massingale said his grandparents decided one night in the late 1940s to leave their home in Belzoni, Mississippi and drive 780 miles north to Milwaukee, Wisconsin, never to return. They were driven out because white supremacists were harassing their friends and neighbors with seeming impunity, and even committing murder.

A Family Uprooted

“My family’s story was a response to a state-sponsored and nationally sanctioned regime of racial terror, a response to a Jim Crow that did not mark the end of slavery but rather marked its evolution,” he said.

Compounding the pain, he said, was the fact that white theologians were silent at the time. Writer James Baldwin helps explain why: He described American society as one characterized by “a cultivated lack of knowing that enables the majority to live at peace with the horror that inflicts so many.”

“Baldwin describes a society as being defined not only by what they know, but also by what they ignore,” Father Massingale said.

Father Massingale said Baldwin’s diagnosis is similar to that of Charles Mills, who described the desire to ignore the reality of racism as “an ignorance that is not merely a lack of knowledge, but the active presentation of itself as real;” and thus akin to a “consensual hallucination.” This results in ethical blind spots, affective callousness, and a refusal to recognize the impact of the past.

Both warned of a form of ignorance that is more than simply the absence of knowledge, but is an “active evasion of knowledge passed off as truth.” The problem, Father Massingale said, is that this is not how ignorance is understood in Catholic moral theology. That’s because it’s primarily concerned with individual actions.

Shortcomings of Catholic Moral Theology

“[It] does not deal with collective ignorance or culturally instilled and supported evasions of moral knowledge,” said Father Massingale. “It does not consider or take account of the blindness that’s produced by the dominant culture and prevents people from seeing the evil dimension of their social reality.”

“What would Catholic moral theology look like if it took the black experience seriously as a dialogue partner?” That, he said, “would entail a wholesale reconstruction of the foundations of the system.”

Father Massingale suggested taking to heart the advice that Baldwin gave in an open letter to his nephew: “With love, we shall force our brothers to see themselves as they are, to cease fleeing from reality and begin to change it.”

“We need a form of ethics that reaches not only the mind, but the inner recesses of the human spirit. Only an authentic theological ethics is adequate for the achieving of human flourishing for captive whites and impacted non-whites, and only such an ethics . . . can formulate an adequate response to the unspoken traumas of history [inflicted upon]us all-but in different ways,” he said.

The Buckman chair was established with a generous gift from James E. Buckman, FCRH ’66, a Fordham Board of Trustee fellow, and Nancy M. Buckman.

Father Massingale joined the Fordham theology faculty in 2016 after teaching at Marquette University for 12 years. Joseph M. McShane, S.J., president of Fordham, called him “a light for our city.”

“[We’re] grateful that you left Milwaukee to be a citizen of New York and a citizen of Fordham,” he said.