Earlier this month Jacqueline Reich, PhD, was invited to speak about her research at the International Silent Film Festival in Pordenone, Italy. The invitation highlighted her role as the first scholar from the United States to officially collaborate with Italy’s national film museum, the Museo Nazionale del Cinema.

Earlier this month Jacqueline Reich, PhD, was invited to speak about her research at the International Silent Film Festival in Pordenone, Italy. The invitation highlighted her role as the first scholar from the United States to officially collaborate with Italy’s national film museum, the Museo Nazionale del Cinema.

For the past eight years Reich, chair of the Department of Communication and Media Studies, has worked with museum staff researching actor Bartolomeo Pagano, better known as “Maciste.” Reich describes Pagano’s immensely popular role as that of the “first Arnold Schwarzenegger.”

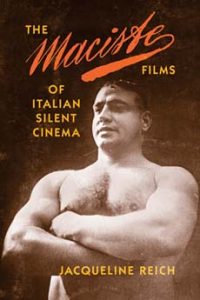

This week, the results of Reich’s research have been published under the title, The Maciste Films of Italian Silent Cinema (Indiana University Press, 2015). The book, with color illustrations, includes an appendix documenting the restoration and preservation efforts at the museum that were in conversation with Reich’s research.

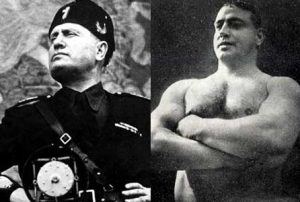

Unlike other male serial stars of the day, Pagano infused his character with irony and humor, said Reich, and his Maciste image permeated the culture. She said there is “overwhelming circumstantial evidence” showing that even Benito Mussolini was influenced by the character.

Reich wrote a cultural analysis in collaboration with the museum’s restoration of the Maciste films. In some cases her research informed the content of the films being restored, but mostly vice versa.

“I really could not have better collaborators,” she said.

Her analysis, in fact, coincided with some the films’ final cuts of the restorations. In one film, Maciste in Hell, Reich noted that the film’s original inter-titles were believed to be a set written in prose; in doing research, a second set of inter-titles were found for the 1926 film featuring tercet metrical poems influenced by the poet Dante. Reich concluded that the second set came about in tandem with the rise of the fascists in Italy, when Dante’s poetry took on an increasingly nationalistic role.

“With the fascists consolidating their power and Italy becoming totalitarian, we understood that the poems added an additional aspect of nationalism, so they chose to restore the film with the poems as the inter-titles.”

A similarity and connectedness between Mussolini and the muscular male Maciste played out in the films, she said.

“If you put images of the two side-by-side, you’d be floored,” she said. “In Italy, movie stars are very ideologically inscribed, regardless of whether the star is apolitical or political—and you can see that influence on the politicians. Just look at Silvio Berlusconi.”

In 30 pages of appendices, the film restorers, Claudia Gianetto and Stella Dagna, detail the restoration process and how Reich’s cultural analysis engaged with the final restoration. One section of the appendix details everything from the graphics of inter-titles to reproducing painted colors.

Such backstage details, said Reich, ensure that the book offers a rare dual perspective of restoration alongside cultural analysis.

“This brings film archivists and scholars into a dialogue about preservation for the first time in book form,” she said.

Maciste alpino (Itala Film, 1916) – frammento 3 from Cineteca MNC on Vimeo.