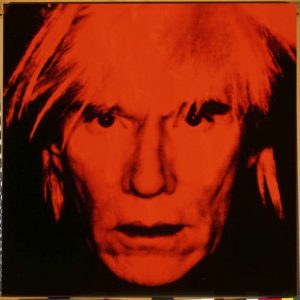

One of the 20th century’s most influential artists, Warhol is more often associated with Studio 54 and his iconic painting of Marilyn Monroe than attending Mass. Scholars of his work know about his Catholicism, but to many fans, his faith is something of a surprise. That faith, and its manifestation in his work, is the subject of a recently opened exhibition at the Brooklyn Museum titled, “Andy Warhol: Revelation.” And, it’s a subject that many students and Fordham experts—in subjects from art history to theology to law—can weigh in on and learn from.

Catholic Versus Spiritual in Art History

“Warhol went into Catholic churches, so he wasn’t just generically quote-unquote ‘spiritual,’” said Laura Auricchio, Ph.D., dean of Fordham College at Lincoln Center, who has published on pop art, most notably on Warhol contemporary Robert Rauschenberg.

“Unlike the Abstract Expressionists who poured and splashed their inner selves onto canvas, Warhol and Rauschenberg drew their imagery from the outer world of commerce and consumption, finding their sources in billboards, magazines, and television,” she said.

Auricchio added that the public doesn’t know much about the faith of 20th century artists because critics, curators, and historians of modernism have largely ignored it. Even a recent New York Times review of the show questioned the depth of Warhol’s faith by citing a biographer who dismissed it and highlighted instead his superstitious nature, pointing out that Warhol also wore crystals. The show, which originated at the Warhol Museum in Pittsburgh, is an important step to not just reexamine Warhol’s faith, but also the faith of modernist artists generally, Auricchio said.

“Van Gogh was actually a deeply religious person, and most people don’t know that, so it’s probably no surprise that people don’t know that Warhol was in a deep and complex relationship with his faith,” Auricchio said. “The history of modernist art has largely written religion out. It has not written spirituality out, but it has written religion out.”

Indeed, it wasn’t until after his death that Warhol’s faith was even acknowledged in public, and in true Warhol fashion it was revealed at the epicenter of New York Catholicism: Picasso biographer John Richardson talked about it at Warhol’s memorial Mass at St. Patrick’s cathedral, said Auricchio.

“It has taken quite a long time for that narrative to take hold and be taken seriously—and that’s something else that really struck me in this show,” said Auricchio.

The Serial Effect

At the start of the Brooklyn Museum show, four icons of St. John, St. Andrew, St. Thomas, and St. Peter are arranged to mimic the altar screen from Warhol’s childhood church, St. John Chrysostom Byzantine Catholic Church in Pittsburgh. Beside them are ephemera from Warhol’s Catholic childhood, including his baptismal certificate.

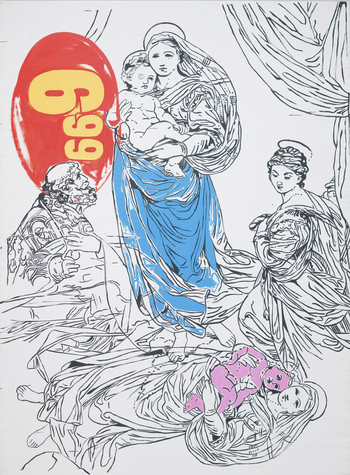

The museum text notes that the way the saints are arranged on screens typically found on Orthodox Christian altars impart a serial effect, like the repetition found in Warhol’s famed silkscreens of celebrities. Indeed, the next section of the exhibition features a series of eight blue canvases titled “Jackie” that reflect that repetition via a series of silkscreens of Jaqueline Kennedy’s face culled from press clippings from just before and after her husband’s assassination.

Appropriation as Art

In museums and art galleries, visitors are generally permitted to take photos for social media, but limitations are placed on photos for publication. Though Warhol frequently pulled photos from the newspaper to use in his own work, as he did in “Jackie,” using Warhol’s imagery of imagery is tightly controlled. Photos of “Jackie” were not permitted for publication.

It’s an irony that’s not lost on Raymond Dowd, LAW ’91, a partner at Dunnington Bartholow & Miller. Dowd is a member of the board of governors at the National Arts Club on Gramercy Park in Manhattan, where another show, “Andy Warhol Portfolios: A Life in Pop | Works from the Bank of America Collection,” closed just a week before the Brooklyn show opened.

Clocking in at more than 1,400 pages, Dowd’s book, Copyright Litigation Handbook (Thomson West, 2010), is a tome on the subject. He said that Warhol’s frequent appropriation—from Marilyn to Campbell’s Soup—probably couldn’t happen as easily today.

“The truth is that until the 1980s and 1990s, America had the weakest copyright laws in the world, which also unlocked tremendous creativity,” said Dowd. “We adopted restrictive copyright laws later on in the game and who knows whether or not that will truly restrict creativity?”

Dowd said that visual appropriation, whether by artists like Warhol, Richard Prince, Jeff Koons, or Shepard Fairey, is never going to be an entirely settled question. In many cases, he said, it’s beside the point. The very action of appropriation is often an artistic act.

“They’re playing with fire. They’re provoking those in power. They’re pushing the boundaries,” he said.

Opening Day: Fordham Deans and Interns

When “Revelation” opened to the public on Nov. 19, Maura Mast, Ph.D., dean of Fordham College at Rose Hill, joined Auricchio to see the exhibit along with two Fordham interns who had worked on the show from as part of Fordham’s Cultural Engagement Internship Program. The deans founded the program at the height of the pandemic; they were grateful to go to the museum in person and meet with students who had conducted research for the Department of Visitor Experience and Engagement.

“When I first learned about the new internship program, I realized that would be a perfect project for a Fordham undergraduate,” said Manager of Visitor Engagement Jessica Murphy, FCRH ‘91. “I recall that during my own time as a Fordham student, access to New York City’s museums and arts-related internships was invaluable.”

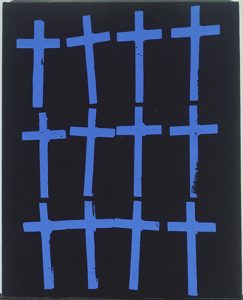

silkscreen ink on linen, 20 × 16 in.

“Revelation” weaves together art history, religion, gender, popular culture, and a New York context in a manner that Fordham’s liberal arts students are ideally prepared to contribute to and learn from, she said.

Indeed, both interns pulled from their Catholic and Byzantine backgrounds to examine and assist in the visitor experience.

Kassandra Ibrahim is a Fordham College at Rose Hill senior and an intern at the Orthodox Christian Studies Center. She said she was initially torn between pursuing art history over theology while applying for graduate schools, but she said the internship helped her come to an academic epiphany.

“I’d like to pursue art history, but I was always drawn back to my courses with the Orthodox Christian Studies Center because I’m interested in studying my own background. This show demonstrated that I don’t have to choose between two,” she said.

Fordham College at Lincoln Center senior Sarah Hujber learned a bit about her background as well.

“I grew up in a small two-mile-wide Polish town on Long Island, so I really related to his Eastern European upbringing and his wanting to move to New York and work in the art scene,” Hujber said. “I always related to that kind of wanting more and being in the busyness of the city.”

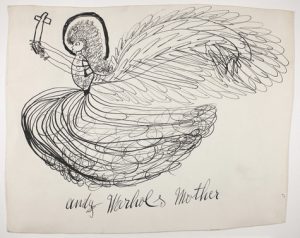

Hujber, who was tasked with researching the women in Warhol’s life, began to learn about the source and loss of many of her own family’s traditions. In examining Warhol’s mother, she viewed an Eastern European immigrant experience that was distinct from yet mirrored that of her family’s.

“I saw a lot of parallels between how my own family ended up here and the kind of traditions I heard about growing up,” she said. “We’re still Catholic, but we probably have lost some of the fullest traditions of Eastern European things that Warhol would have been a part of.”

An Icon’s Icons

Warhol’s parents, Andrej and Julia Warhola, immigrated to Pittsburgh from present-day Slovakia, a place that was once part of Czechoslovakia, which in turn was part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire and the Byzantine Empire before that. As such, the ever-shifting borders have little to do with Warhol’s ethnic identity, said Aristotle “Telly” Papanikolaou, Ph.D., the Archbishop Demetrios Chair in Orthodox Theology and Culture and co-founding director of the Orthodox Christian Studies Center. Warhol’s ethnicity has been variously described as Polish, Slovakian, and even Ukrainian—but his ethnicity was Ruthenian.

“I’m somewhat oversimplifying, but the Ruthenians were part of a group of Orthodox that are now part of the Catholic Church, who were able to keep their vestments, rituals, and married priests as long as they pledged allegiance to the pope,” said Papanikolaou. “Part of the Ruthenian heritage is an iconographic tradition and that’s one of the things that remains very much a part of them and why they’re sometimes called Greek Catholics.”

As mentioned, Warhol’s childhood church was indeed filled with Greek-influenced icons painted in the early 20th century and arranged in rows as part of the altar screen. But Papanikolaou noted that the four icons in the exhibit have a slight Western influence.

“Orthodox Christians went through a weird inferiority complex in the late 19th and early 20th century where their icons took on a bit more of a kind of naturalistic style. In other words, the figures evoke a bit of the Renaissance, but not in totality,” said Papanikolaou. “They melded these two traditions in ways that were really unique. It was only from the ’60s on where people started to go back to the original Byzantine style.”

Through her internship, Ibrahim learned about melding influences; she talked about how they carried on throughout Warhol’s work and can be seen in the show.

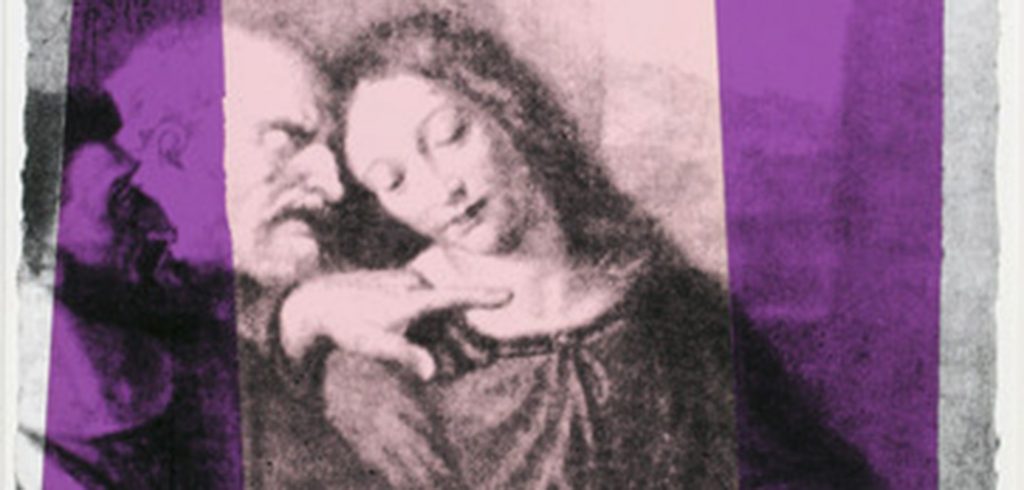

“He’s inspired by both the Byzantine aspects of iconography, and the iconic image of an individual in a one-point perspective, but then we see his Last Supper paintings [based on DaVinci’s]and you can see the influence of the Renaissance,” said Ibrahim, who was raised in the Greek and Coptic Orthodox traditions. “It’s kind of a mix because Byzantine Catholicism is also a mix. It is a fusion between an Orthodox visual reality and then Catholic doctrine. So, it’s in communion with the Catholic church, but visually it looks very Orthodox.”

‘The Symbol Is Everything’

Papanikolaou said that the flat one-point perspective of the early Byzantine icons is sometimes dismissed as being somewhat primitive, which does the artists and the church that commissioned them a disservice.

“They knew what they were doing,” he said. “They were trying to not look realistic because there trying to capture not just a historical event of the past but also point to an internal significance of the moment or a transcendent divine in the historical moment.”

Conversely, he said, an early renaissance painter like Giotto might paint the baby Jesus in a more realistic and cherubic manner to help the viewer to identify and participate in the earthly life of Jesus. Iconographers were not simply reminding believers of events, but rather they were symbols that allowed viewers to participate in an eternal reality.

“The symbol is everything, in a way, because the structure of the symbol really determines what it is that the viewer can participate in,” he said. “From that point of view, I can really see Warhol being influenced by that tradition. I think he’s trying to say that there is something of an eternal significance going on within these particular figures and even the particular events they’ve experienced in their lives.”