“He had classmates from Eastern Europe, from Italy, from Ireland, from parts of Asia—just lots of different places in the world,” said his daughter, Rachel Harding, PhD. The experience “gave him a grounding and commitment” to seeing a true multicultural democracy take hold in America, she said.

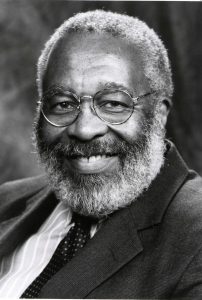

Realizing that ideal was a lifelong calling for Harding, a nationally prominent civil rights activist who was interviewed in 2005—nine years before his death—for Fordham’s Bronx African American History Project (BAAHP) oral archive.

A leading scholar on the links between religion and social justice efforts, Harding gave intellectual grounding to the civil rights movement, wrote speeches for Martin Luther King, Jr., and played a key role in creating the field of African American studies. And his New York roots were critical in shaping who he would become.

Born in Harlem and raised by his mother, he was deeply involved at the Victory Tabernacle Seventh Day Christian Church, a tight-knit local church on West 138th Street that nurtured his leadership and writing abilities so that he stood out when he arrived at Morris High School in the Bronx, Rachel Harding said.

As Harding put it in his BAAHP interview, “people believed in me absolutely and expected very great things from me” at the church. “The church was very, very conscious of the need to develop leadership capacities in the young people.”

At Morris High School, Harding shined because of the encouragement he got from teachers and advisors who embraced integration, said Rachel Harding, a professor of indigenous spiritual traditions at the University of Colorado, Denver.

Harding would come to believe that strong black institutions like his church, rather than being “separate,” were essential for making a multiracial society work, said Mark Naison, PhD, a Fordham professor of African American studies who interviewed Harding for the BAAHP oral archive.

“The combination of those two, of a strong foundation in a black institution and being part of an interracial institution, were what gave [him]the wherewithal to be a leader in the civil rights movement,” he said.

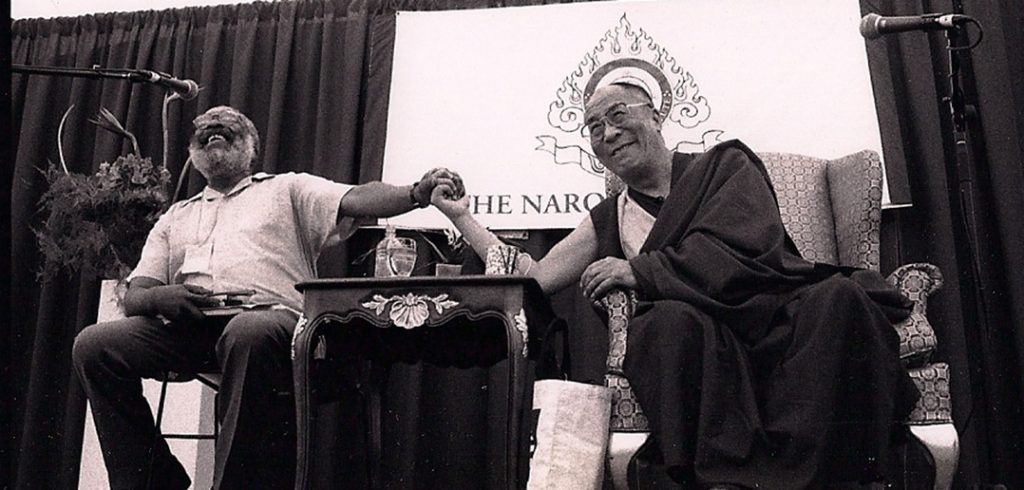

After earning a doctorate in history at the University of Chicago, Harding taught at many institutions including the Iliff School of Theology in Denver, where he was on the faculty for nearly 30 years. In 1960, he and his wife, Rosemarie Freeney Harding, co-founded Mennonite House in Atlanta, giving the region its first black-led social service agency, and took part in civil rights campaigns throughout the South, befriending Martin Luther King, Jr., along the way.

Harding would become one of King’s “right-hand people” and a critical adviser in King’s decision to speak out against the war in Vietnam in 1967, said Brian Purnell, PhD, a former Fordham professor who interviewed Harding along with Naison.

“He was a consistent humanist, and that mostly came out in his total opposition to war,” said Purnell, now a professor of Africana studies and history at Bowdoin College.

Her parents avidly explored the links between spirituality and social justice “across a tremendous range of [religious]traditions,” Rachel Harding said.

“One of the things that my dad and mom talked about almost with the joy and reverence of a kind of religious experience was how powerful that nonviolent social justice movement of the South was,” she said. “‘To really redeem the soul of the nation’—that’s the way those people talked about it, and it wasn’t just rhetoric for a lot of them.”

When Harding returned to Morris High School for his Bronx African American History Project interview in 2005, Naison noticed his spiritual influence.

“I was in the presence of someone who was just really special in his compassion, generosity, his insight and in his commitment to always find the best in people,” said Naison. “He’ll make you see things which you actually have thought, but suddenly see them with an emotional resonance and a depth that makes you feel better about who you are.”