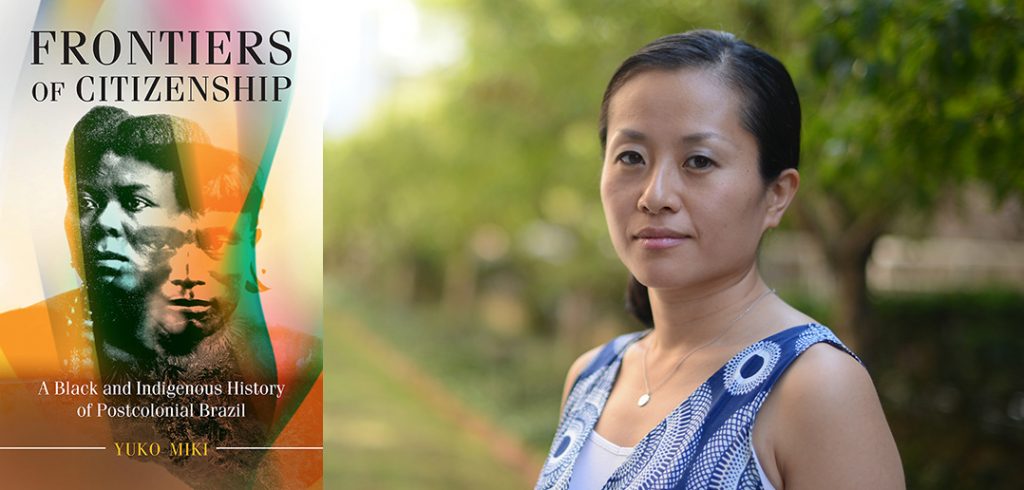

(Editor’s note: In February 2018, Miki published the results of her research below as Frontiers of Citizenship: A Black and Indigenous History of Postcolonial Brazil (Afro-Latin America) (Cambridge University Press, 2018))

In the United States, the Civil War, the Emancipation Proclamation, and the Underground Railroad loom so large in the understanding of slavery that most Americans can almost be excused for thinking it’s a phenomenon unique to the country.Yuko Miki, PhD, assistant professor of history, wants to vastly expand that understanding of the system—particularly its role in the South American nation of Brazil, which had the distinction of being the last country in the Americas to outlaw slavery in 1888.

An expert in Iberian Atlantic history, Miki has looked at Brazil’s connection to slave trading firms in the United States, to slave traders in West Central Africa, and to British abolitionists.

The picture of slavery as a national institution has been too small, she said. “It’s very exciting to be able to look at the history of slavery in a more transnational way.”

Though she’s originally from Tokyo, Miki became fascinated in college with the performing arts of the African diaspora, and later took classes at the Ailey School. A former practitioner of the Brazilian martial art of Capoeira, Miki went to Brazil and found the country to be ideal for her research.

When she began researching 19th-century slave resistance in Rio in 2006, however, she stumbled upon numerous stories of indigenous rebellions. This was puzzling, she said, because there’s a very strong narrative in Latin American nations with large black populations that indigenous people were wiped out in the 16th and 17th centuries by Columbus, the Conquistadors, disease, and famine.

“I began to realize that in fact, the history of indigenous people in Brazil is very much a missing piece of history,” she said. “They were enslaved and lived and worked alongside slaves of African descent until the eve of the 20th century. For too long we had presumed that African slavery had expanded into ‘empty’ lands, which in fact were indigenous territories.” These histories, long separated, are in fact deeply connected.

Bringing these stories to light now is important, she said, because they challenge enduring popular narratives in Brazil. In The Masters and the Slaves (1946), for instance, sociologist/anthropologist Gilberto Freyre argued that the country is a “racial democracy”—composed of the race mixture between black, Portuguese, and indigenous people—and because of that, there is no racial tension in Brazil.

But just because people are of mixed race doesn’t mean there was or is no conflict, Miki said.

“It’s still important to look at the actual history of Brazil’s black and indigenous peoples. You don’t want to just look at the end result of a mixed society and celebrate it; but also look at how such race mixture might have occurred,” she said.

Her current project, which she worked on during a spring fellowship at Yale University, focuses on the overlapping geographies of the Atlantic World.

“I’m really interested in geography, not just in the physical sense of space or terrain, but also in the ways people conceptualize space and how they give meaning to space,” she said.

One of those geographies—the Middle Passage—can also be defined through narratives, such as that of two West African men whose stories Miki found in crumbling, barely legible scripts written in 19th-century Portuguese. Their stories about their journey from Lagos, Nigeria to Bahia, Brazil, and another set of documents pertaining to a slave ship from Angola bound for Rio de Janeiro, offer a rare glimpse into that horrific experience.

Further complicating their story is the fact that one of the ships was in fact illegal, and its interception before it arrived in Rio caused a diplomatic uproar at the time.

“I want to look at the Atlantic world as a place of overlapping geographies of personal narratives of capture, of slave ships, as well as capital, and this political movement of abolitionism.”

This challenge to think about slavery in new ways extends to Miki’s teaching too, in courses like Rebellion and Revolution in Latin America and the Atlantic World, and Slavery and Freedom in the Atlantic World. For example, she wants students to understand that the abolition of slavery was not an inevitable outcome; many places, from Cuba and Haiti to Puerto Rico and Brazil, wanted to preserve slavery while speaking of equality. It was the enslaved people themselves who challenged slaveholders’ hypocrisy and fought for their own emancipation.

“History is not about just facts. It’s all about competing narratives, and is very much about the present. If we think about what’s been happening in the United States recently with #blacklivesmatter, it’s very hard to separate it from the past,” she said.