What was once a barely legible reproduction of an eight-century-old map now lives online in vivid, interactive detail, thanks to a project at the Center for Medieval Studies.

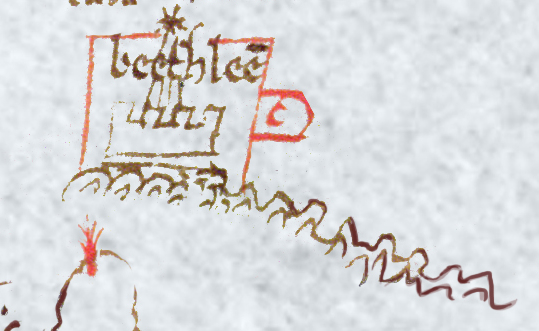

The Oxford Outremer Map project is a collaboration among the center’s faculty, students, and fellows to restore a 13th-century map that depicts the coastline of the Crusader states, now modern-day Israel and Palestine. The map was likely made or copied by an English monk named Matthew Paris, said Laura K. Morreale, PhD, associate director of the center, and offers a glimpse into various—sometimes abstract—functions of medieval maps.

“It’s very different than how we understand maps today,” Morreale said. “Some of the locales are biblical, so they’re not recognizable in modern terms. A couple places even depict what the mapmakers thought would happen in the future. So, not only is it a practical map, it’s also a kind of visualization of what they hope will happen one day.

“That’s part of the larger conversation,” she said. “Maps should be approached the way you would approach a piece of literature. You don’t just look at the text, but you think about its context and the material reality that surrounded it.”

When Nicholas Paul, PhD, an associate professor of history, encountered the map reproduction as part of the center’s French of Outremer digital humanities initiative, he found the document in poor condition. Besides suffering the expected wear-and-tear over eight centuries, the map had been drawn on the back of a used sheet of parchment. Over time, the colors on the front bled through and obscured Matthew’s drawings and notes.

For years the map was overlooked by medieval scholars, despite its depiction of an important region. Hoping to make it legible again, Paul and Tobias Hrynick, a doctoral student in history, brought the map to the Medieval studies center, where then-graduate student Rachel Butcher, GSAS ’15, worked to spruce it up in Photoshop.

The result is a full, colorized digital version of the map, complete with interactive features and annotations written by the graduate students and fellows.

“It’s not just digitally presented—it’s digitally enabled scholarship,” Morreale said. “It’s user-guided, so users can interact with the map on their own terms. There’s also a discussion section, where users can write in with their input, and there’s a ‘mysteries of the map’ section, where we list the parts of the map we haven’t yet been able to identify. We’re encouraging people to write in if they have some knowledge about these.”

At a colloquium on April 9, scholars discussed the significance of both the map itself—including its relevance to medieval cartography and whether Matthew Paris was indeed its author—and how scholars can use the digital restoration to maximize teaching and research.

“We’re in the process of creating a module for people who want to use this map in classrooms,” Morreale said. “That, in my mind, has been one of the greatest aspects of this project. We were able to take a discussion in our office and project it out into the larger, scholarly world. It’s now accessible to anyone who is interested, with just a few clicks.”