What is left to say about Nina Simone, a musician whose life and work have been chronicled by numerous biographies, documentaries, and exhibits?

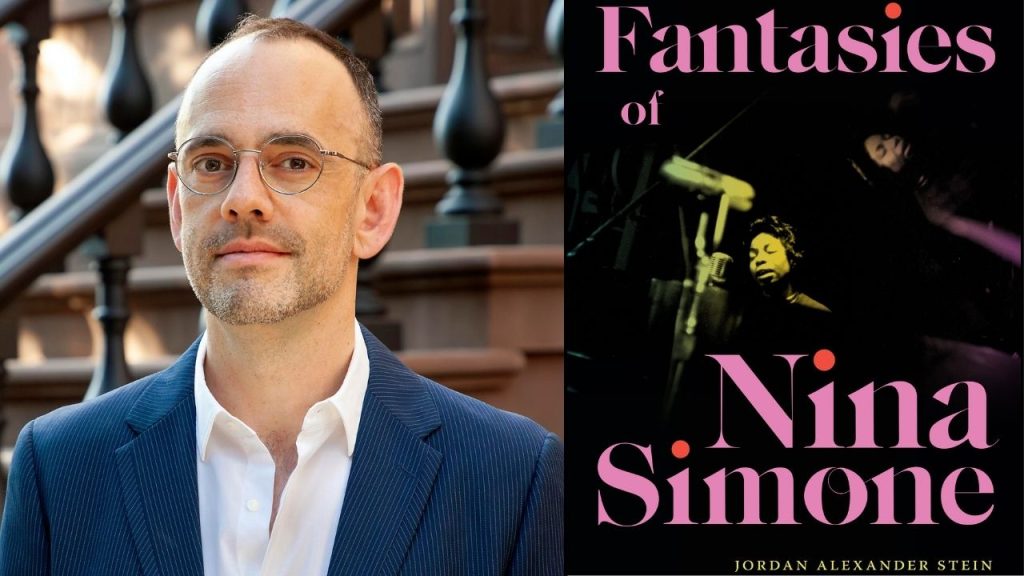

According to professor Jordan Alexander Stein, Ph.D., there are deeper truths left to explore through the lens of fantasy: Simone’s fantasies about herself, as well as those residing in our cultural imagination.

“Fantasies always express something that is at some psychic level genuine to the person expressing them,” writes Stein in his new book, Fantasies of Nina Simone (Duke University Press, September 2024). The book is an exploration of Simone’s life and work, and the ways she constructed her artistic persona to claim race and gender privilege that weren’t available to her otherwise. It’s also an exploration of the public’s relationship with Simone, and how we’ve lost some of her complexity in making her an icon.

A professor of comparative literature in Fordham’s English department, Stein draws his conception of fantasy from psychoanalysis, which holds that, like free association and “Freudian slips,” our idle daydreams offer insight into the unconscious mind.

“Yes, fantasies can contain lies, falsehoods … and any number of other conscious or unconscious delusions,” Stein writes. “Yet the appearance of these dishonesties … tends very much to reflect things we honestly wish or desire.”

Breaking Barriers

According to Stein, who drew upon a vast archive of her performances, images, and writings for the book, we can find clues to Simone’s desires in her subtle artistic choices. The way she injected a word with unexpected melancholy, or the songs she chose to cover and the way she chose to cover them, often point to a wish to rise above the confines of her marginalized identity as a Black woman.

For example, Stein notes, when Simone covered Leonard Cohen or Bob Dylan, she rarely switched the pronouns from “she” to “he” when singing about a love interest, as many singers do. Her choice to cover these white male artists at all is notable. Through her music, “she’s claiming certain kinds of race and gender privilege that weren’t afforded to her in other ways,” Stein said.

A One-of-a-Kind Icon

So, why choose Nina Simone’s music for this exploration? Because, Stein said, “There’s nothing like it.”

He related a story about ’90s musician Jeff Buckley covering “Lilac Wine” and calling it a “Nina Simone song” without seeming to realize he was covering a cover. “[Her music] is so unique and beautiful that people don’t even understand this is secondhand material. She’s so thoroughly made it hers. It’s a power that some artists have, but not many,” said Stein.

And what about our collective fantasies of Nina Simone? Psychoanalysts might say she’s reached archetypal status, a shorthand for Black female genius, empowerment, and transcendence. Stein notes that it’s easy to forget she never got to view herself from our future vantage point, a distance that blurs much of the messy nuance of an extraordinary life.

He hopes to restore some of it.

“The reputations people have after they die are not always the complexity they lived in,” he said. “To honor both things and not collapse them into each other is part of the project of the book.”