So was Yayoi Kusama, an artist who had traveled from her native Japan to join the burgeoning scene.

A new book by Midori Yamamura, PhD, Fordham’s lecturer in the Department of Art History and Music, examines the contributions of the petite and authentically outrageous artist who had gallery shows with some of the leading artists during the sixties, and who hoped to achieve “the same level of recognition as her white male peers,” said the author.

Yayoi Kusama, Inventing the Singular (MIT Press, 2015), is a critical biography of an artist who grew up in Japan’s military culture of World War II, which was devastated by two atomic bombs that fell 70 years ago this month. By following Kusama’s footsteps in Japan, the United States, and Europe, Yamamura examines artistic developments that emerged out of the totalitarian societies of the war, notably the postwar globalization of art.

“Kusama was a very central figure in the New York sixties art scene,” said Yamamura, a scholar of modern and contemporary Asian art, “But she became almost as famous for her self-proclaimed mental illness and permanent residence in a psychiatric hospital as she was for her art.”

Yamamura said she became interested in Kusama after she read the artist’s 2002 biography, in which Kusama wrote how important and influential she was in New York. Yamamura dug up archives, researched Kusama’s account, and found that she was indeed an influential figure. Yet she didn’t realize the same prestige as her male peers, such as getting important dealers. Upon her return to Japan in the 1970s, Kusama was similarly ignored and had a major nervous breakdown in 1975. She has been residing in a mental health facility since 1977.

“I became interested in how a woman artist gets overlooked by a society,” said Yamamura.

She visited Kusama at her studio near her hospital in Tokyo and secured access to her archives—including her daybook from 1960-63.

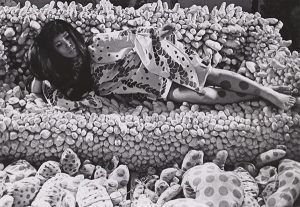

Through the chronology, Yamamura discerned that Kusama first developed soft sculptures—furniture covered by sewn-fabric protuberances—for a joint show in June 1962 with artist Claes Oldenburg. Following the show, inspired by what he called Kusama’s “psychotic art,” Oldenberg entered into his own soft sculpture period, creating giant ice cream cones and huge hamburgers made from canvases.

“She was sewing soft sculptures before he,” Yamamura said. And yet when Oldenburg was interviewed about Kusama in 1989, “he did not have the courage to say that he’d been influenced by this Japanese woman.”

In the late sixties, seeking to inspire an expansion of people’s ideas, Kusama ventured into psychedelic light shows of sound, flashing lights, and projected imagery that became a precursor to her more politically charged protofeminist art. She also staged “Anatomic Explosions,” press happenings protesting the Vietnam War in which she painted on nude models. They were, she said, less obscene than real war.

In the 1990s, Kusama’s work experienced a revival that continues today. In 2012, London’s Tate Modern held a retrospective of the artist’s work. At age 86, Kusama is recognized as one of the most important living Japanese artists, whose anti-conformist work is “not easily absorbed into a totality.”

“That is the singularity of Kusama’s exercise,” said Yamamura. “Seeing her life through her own eyes has enabled me to look at postwar art history, and to better understand the thoughts and expressions that came out of this society and through globalization.”

— Janet Sassi