Like all New Yorkers, Angela Alaimo O’Donnell, Ph.D., saw her world turned upside down by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Knowing that what was happening was unprecedented and looking for a way to bear witness to this historic moment, she sat down at the beginning of quarantine and began documenting life through a series of new sonnets, the first one titled “The Fire.” A year later, she concluded with one called “Anniversary.”

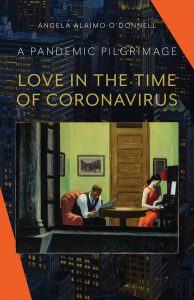

On June 8, she published 58 of those poems in Love in the Time of Coronavirus: A Pandemic Pilgrimage (Paraclete Press, 2021).

O’Donnell, an associate director of the Curran Center for Catholic Studies who also teaches undergraduate students, said she hopes the book will serve as a time capsule for those who have lived through the pandemic and those seeking to learn about it in the future.

O’Donnell, an associate director of the Curran Center for Catholic Studies who also teaches undergraduate students, said she hopes the book will serve as a time capsule for those who have lived through the pandemic and those seeking to learn about it in the future.

In poems such as “In Which I Consider My Wardrobe” and “The Virus Remakes the World,” O’Donnell said she was aiming to document both her own personal experiences and those felt by others, especially in the New York region.

The former resurrects a time in which street and work clothes appeared to be destined never to leave our homes:

Six pairs of boots lined up in a row.

Three black suits hung limp in the closet.

“The Virus Remakes the World,” on the other hand, reflects on the way nature seemingly filled the void as humans retreated to safety:

The animals are taking back the earth.

Birds build their nests in the air conditioners.

Enduring a Collective Isolation

“Many of us suffered under lockdown. None of us were able to go to the theaters or restaurants, bars or movies; none of us were able to meet with our friends the way were used to,” she said.

“I began then to see the poems as a chronicle of a very strange time that we endured alone and together.”

The poems are grouped into four sections and follow a chronology roughly akin to the four seasons. The first features titles like “House Arrest” and “Survival;” the second has pieces such as “Wherein I Miss My Children” and “Palm Sunday.” The third and fourth sections recount the resurgence of the virus and, ultimately, offer glimpses of hope in “The Virus Begins to Abate” and “Pandemic Epiphany.”

One of the first poems that she wrote, “COVID Has Made Me Stupid,” explores the disorientation she felt in the initial weeks of lockdown with the opening lines:

Good books line my shelves but I don’t read them.

Three sentences in and my mind wanders off

like a toddler in search of a snack . . .

In November, The Christian Century published the poem, and the responses were illuminating.

“I can’t tell you how many people wrote to me and said, ‘This describes exactly how scattered my mind has been for the last few months,’’ she said.

“I realized that my experience isn’t an isolated one. There are other people who are going as crazy as I am trying to figure out how to live our lives: What are the risks? What should I be doing? What can I do? What can I not do?”

A Reflection on Teaching

Some of her pieces are more specific to her own life, like “Wherein I Teach Remotely.” Teaching was a very poignant, moving experience, she said, and reminded her of what it was like to work with students in the aftermath of 9/11.

“All of a sudden, literature became very relevant because literature offers the wisdom of the ages and insight into the circumstances of the human condition. Suddenly four-hundred-year-old Shakespeare plays that were about doom and disorder and the undoing of a grand kingdom—that’s what was happening to us,” she said.

Capturing the ‘Interior’ Drama

Although “COVID Has Made Me Stupid” features a line that mentions the president, the poems steer clear of other major cultural and political developments of the past year, such as the murder of George Floyd and the insurrection at the U.S. Capitol. That was a conscious decision. “My writing poetry about George Floyd’s suffering risks voyeurism and could be seen as presumptuous and writing about insurrectionists could easily come across as preachy,” O’Donnell said.

“As W.B. Yeats once wrote, ‘Out of the quarrel with others we make rhetoric; out of the quarrel with ourselves we make poetry.’ Poetry is always trying to capture the interior drama that’s going on because we all live with mixed feelings,” she said.

“I really wanted the focus to be on the virus and the ways it changed our lives.”

A narrow focus also allowed her to explore poetic form more. “Pandemic Acrostic,” for instance, is her first published acrostic; the first letters of the 14 lines spell out “COVID19” forward and then backward.

“I thought it was a fun exercise, even though it’s a serious subject—to just play with the language and this interesting name that was never a part of our lexicon before and has now become a word we all know and use daily.”

A final poem, called “Pandemic Prayer,” ends the book with these hopeful lines: “The virus can’t destroy / this urge to bless our lives & praise / even these pandemic days.”

“Saint Ignatius always reminds us that we move between the poles of desolation and consolation—times when we feel God is distant and absent from our lives and times when we feel God’s presence, when we’re assured that things are going to be okay and that there is a providential design in all of this,” she said.

“Even in the midst of suffering, there is blessing.”