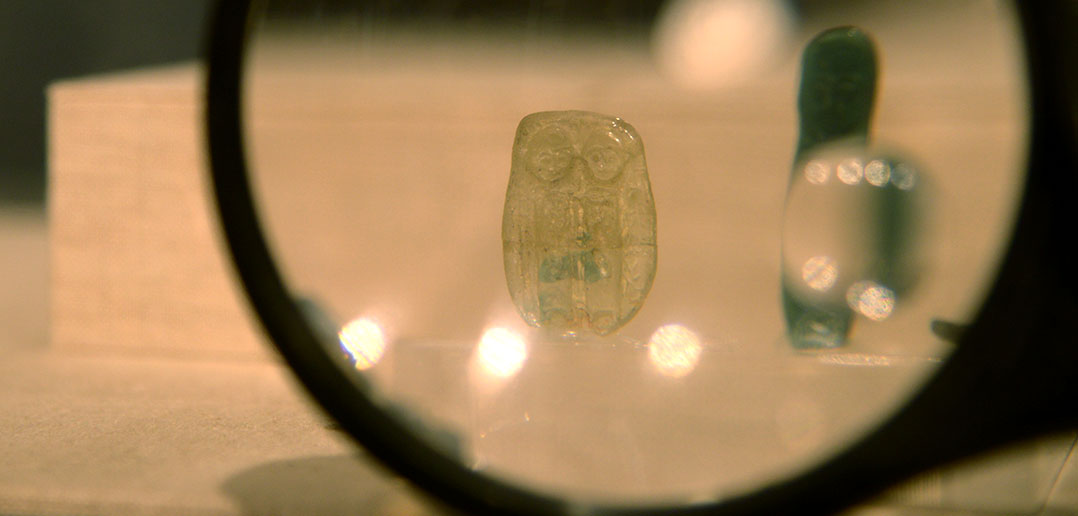

The exhibition employs the same pedagogical goals Udell has championed since the museum opened in 2007, where students research an object’s origin and history to create a teaching museum. All 76 objects, which range in origin from the 6th century B.C.E. through the 10th century C.E., were selected and researched by 19 student curators. Students spent an entire semester in Udell’s Museum Studies in Ancient Art course studying one or two of the mass-produced objects, which do not necessarily yield the same depth of interpretation as studying a unique painting or sculpture, said Udell. Students had to rely on scant scholarship and fill in the blanks themselves by examining the history of glass, literature of the period, geography, and patronage to determine their use.

Glass, h: 1 3/4”; 1 3/8”; 1 1/16”

Gift of Lillian Sel Schloss

Researching Together

“We were learning about glass together,” said Udell, who specializes in ancient terracotta vases, not glass. “Together we realized how ambiguous the scholarship was and it was left to us to pull out the most plausible uses of the objects.”

She noted that art history has just as many unknowns as the sciences. And, just as in Fordham science labs, art history undergraduates conduct research in the arts; in this case, the lab is the museum and its collection. Udell teaches students to employ the same research techniques used at any major museum.

“I told the students that unlike other assignments they may have had in the past, they won’t always have the evidence right in front of them and they were going to have to get comfortable with not knowing,” she said, adding that students sometimes need to look beyond the collection and literature and go to other institutions to make their own connections.

Drawing Connections

Sophomore Samantha Armacost, a double major in classical civilizations and art history, said most of the scholarship she found was on more refined glassware, not on the mass-produced objects found in Fordham’s collection.

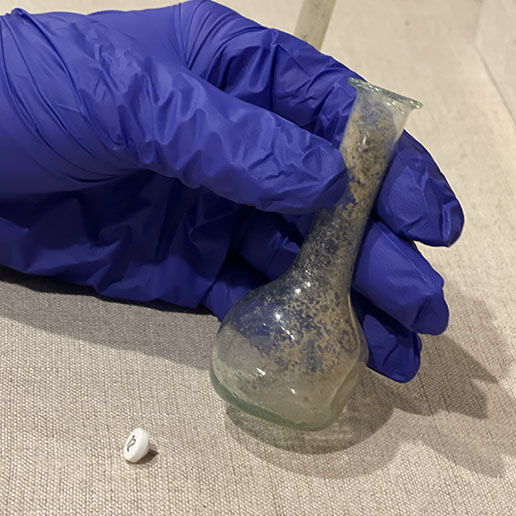

“We have very nice glassware, but it’s certainly not the elaborate stuff that you usually see in other museums like at the Met,” she said. “I couldn’t find much on my objects, which were little glass bottles that couldn’t hold much liquid or anything, so nobody really knows what they were used for.”

Armacost said that she found that by expanding parameters of research beyond the object itself she began to get closer to hypothesizing what her set of objects were about. Her particular objects appear to be one-inch-high jars with bulbous bodies that narrow at the neck and flare back out at the top. Most objects of a similar shape have been found throughout what was the Roman Empire from the 2nd to 4th centuries C.E. Armacost said that the little jars had little practical purpose in daily life. She found suggestions that they could have been used to hold cream or ointments, but she ultimately concluded their narrow necks wouldn’t allow for easy access to the contents. She also found evidence to suggest that they may have been worn suspended by a cord as a pendant. But ultimately the color, shades, and tone of the glass told a bigger story.

Roman, free-blown, 1st-4th century C.E.

Glass, h: 3”

Gift of Oscar Magnan, S.J.

The Chemistry of Art

Udell had already told the students that the chemistry behind the variety of colors, shades, and iridescence in the collection are great indicators of where an object comes from and how it was made.

“The iridescence is just something that happens naturally when glass becomes exposed to burial conditions, soils and leaching; it just comes naturally,” said Udel. “Believe it or not what we look at as the beautifully iconic aqua, blue-green, and turquoise color glass, that was just the natural color of glass, nothing was added to make that color. It’s a natural byproduct of the sand, the ash, and sodium, used to make the glass.”

With that in mind, Armacost concluded that her objects were likely grave goods, which she wrote in the exhibition text next to the objects in the museum. There, she wrote that the jars’ iridescence indicates they were buried for a substantial amount of time. She then paralleled the jars with similarly “impractical objects” in the Metropolitan Museum’s collection that were found in tombs of Cyprus. The surface color and the parallel collection at the Met led her to conclude that the plausible purpose was as “grave goods.”

Humble Objects with Staying Power

That the jars were mass-produced hardly detracts from their impressive staying power, said Udell.

“These commonly made, humble objects defy our expectations for survival because they are so fragile and they’re still here,” she said.

Of course, other collections have the regal purples or include clear glass, both attributes associated with wealthier households.

“The really prized glass of antiquity was absolutely colorless like our glass today, like what we use for drinking glasses,” she said. “The reason for that was because the thought is that glass was meant to mimic rock crystal. They were going for something imitative.”

But the glass in the Fordham collection would have been found in a modest Roman home, said Armacost. She cited an amusing anecdote from her research on the literature of the time. She noted that in Petronius’s Satyricon, a pretentious wealthy character who, though he prefers the tasteless quality of glass, drinks out of metallic cups because glass is simply too common.

“I personally prefer glass, at least it doesn’t give off a smell,” he says. “If it were not so breakable, I’d prefer it to gold, and now as it is, it’s cheap.”