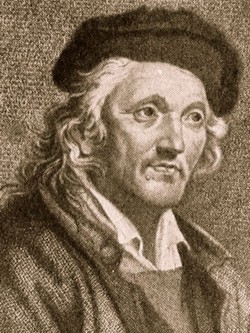

However, it was his 1707 treatise Musicalische-Paradoxal Discourse that gave readers insights into the framework that inspired his musical discoveries, says Fordham College at Rose Hill senior Melani Shahin.

Shahin, who is studying philosophy and music, with a minor in religion, had the chance to study Werckmeister’s quadrivial approach to musical thinking this past summer through a Fordham undergraduate research grant. She will be presenting her research at the 11th Annual Undergraduate Research Symposium on April 11.

A self-educated Baroque composer, Werckmeister believed that there were convergences between music and the cosmos, she said.

“To Werckmeister, music was related to science, mathematics, theology, religion, and a lot of disciplines,” said Shahin. “Other theorists of the time made fun of treatises like Musicalische-Paradoxal Discourse because they found his abstract theoretical approach to be antiquated.”

With guidance from Eric Bianchi, Ph.D., assistant professor of music, Shahin studied the ways Werckmeister’s philosophical and theological digressions challenged professional hierarchies of music.

Recently, she was one of about 80 college students from the East Coast who were selected to present their research at Moravian College’s 12th Undergraduate Conference in Medieval and Early Modern Studies, in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania.

“As an organist, Werckmeister wasn’t considered a high-status musician,” said Shahin, whose presentation focused on the implications of Musicalische-Paradoxal Discourse. “I think part of the reason why he talks about math, science, and other disciplines is that he’s trying to build credibility as a music theorist.”

Finding Connections

Werckmeister didn’t study at a university, but he was knowledgeable about medieval and Renaissance writings about music, she said. He gravitated toward the work of German astronomer Johannes Kepler, founder of the three major laws of planetary motion. Like Kepler, Werckmeister was Lutheran, which Shahin said is critical to understanding his perspectives.

“Even though the Lutheran worldview was mostly grounded in the Bible, people like Kepler and Werckmeister are proof that there was a big interest in science,” she said.

Two years ago, Shahin took a course at the Goethe Institut in Berlin, which helped her to translate several original passages from Werckmeister’s Musicalische-Paradoxal Discourse.

“In the treatise, Werckmeister is pulling on so many different sources, which shows that, to him, religion and science weren’t at odds,” she said. “Werckmeister wanted to show that God made the universe and music and that they’re all connected.”

The calculations that Werckmeister used to support his view that an organist’s work had spiritual value were ultimately unfounded, said Shahin.

Still, she doesn’t think his musical theories should be discounted.

“Back then, people sought connections in their lives,” she said. “Werckmeister didn’t just see numbers or musical notes. He saw symbols that were loaded with meaning. It’s a different approach than the way we understand music today.”