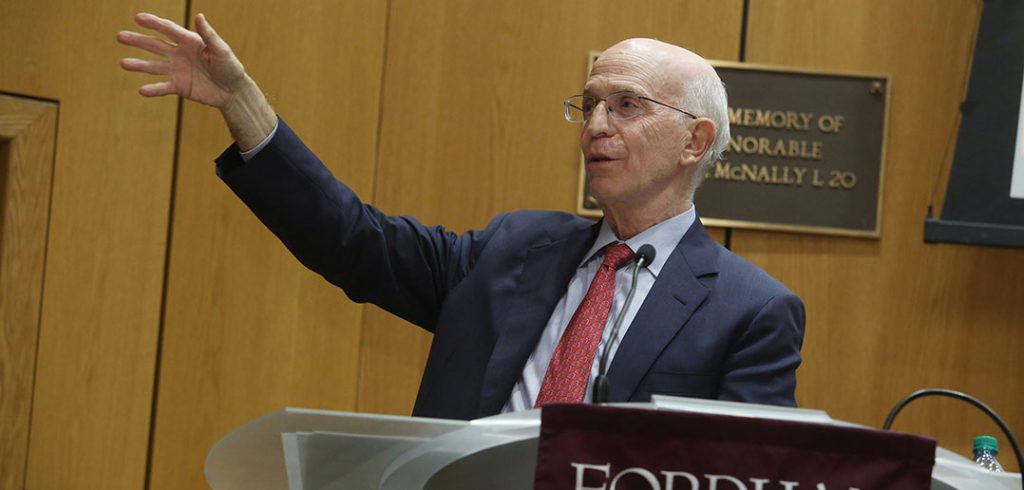

“The two civilizations,” as Blinder termed them during a one-hour talk and discussion at McNally Auditorium on Sept. 17, “don’t get along very well.”

Speaking to an audience of more than 150 Gabelli School of Business students and alumni, as well as members of the Alternative Investment Roundtable and the Fixed Income Analysts Society, Blinder outlined the reasons for the fissure and suggested a few corrective measures.

Although Blinder was clear at the talk’s outset to which camp he belonged, saying that “politicians use economics in the same way that a drunk uses a lamppost, as a source of support not as a source of illumination,” he said each side could learn something from the other.

While economists rely on historical data, dispassionate analysis, and a long view to maximize society’s well-being, politicians have no such compulsions, much less obligations. Yet politicians are the ones who by and large create economic policy, most of it through tax and trade legislation and treaties, to cite two policy cornerstones which Blinder emphasized during his talk. And politicians are further enabled by a voting public that has little knowledge or patience for economic theory or policy, Blinder said.

“The main selection principle for a policy, if the selection is being done by an economist, is what is good. … In politics, it’s more typically what sounds good,” he said. “If you’re a politician, your success criteria is obvious: It’s how you do on election day.”

Blinder, the author of the recently published book Advice and Dissent: Why America Suffers When Economics and Politics Collide, tailored his remarks to his audience, suggesting a number of ways economists must engage both the public and politicians to counter what he called the “false beliefs” preached by politicians, particularly with regard to trade and tax legislation.

To achieve that, Blinder said economists must master what he called a “four-ring circus” comprising substance, politics, message, and process if they are to succeed in pushing through sound economic policy.

The first ring, substance—whether regarding tax policy, regulatory policy, monetary policy, or trade policy—is the economist’s forte and needs no strengthening.

But grasping the nuances of the other three “rings” is essential, if nonetheless challenging given that most economists lack the necessary interest and assertiveness. Economists, he intimated, must conquer their dislike of politics as well as their disinterest of the field to make any inroads on the legislative front.

Economists must also overcome their reluctance—in some cases, their inability—to convey their message in terms accessible to the public. “Message is really important if you want to move the electorate,” he said. “And if you want to move the politicians, you have to move the electorate.”

Process, which links the other three categories, is also looked on with disdain by economists, much to the detriment of their policy arguments, Blinder said.

“So the upshot is that if you’re deficient in politics, message, and process, you’re going to have a hard time influencing policy even if you’re super, super, wiz-bang right about the substance of the policy,” he said.

The overriding challenge for economists is to convince the public and politicians of the solidity of their positions, Blinder said—an imperative complicated by economic theory’s indisposition to the lifeblood of politics: compromise.

As such, Blinder, who writes a monthly column in The Wall Street Journal, sounded a note of caution.

“The notion that a bunch of economists like me can make an appreciable dent on the economic literacy or illiteracy of the population at large is fanciful,” he said at his talk’s conclusion. Still, he said, “I try.”

The event was presented by the Gabelli Center for Global Security Analysis, the Fixed Income Analyst Society, and the New York Alternative Investment Roundtable.

–Richard Khavkine

[doptg id=”120″]