That was the message Marciana Popescu, Ph.D., associate professor at the Graduate School of Social Service, wanted to drive home during a talk to alumni, students, and staff this week.

Her discussion, “The Silent Pandemic—Mental Health Implications of the COVID-19 Pandemic for the Most Vulnerable,” which was organized by the Office of Alumni Relations, highlighted how the pandemic has impacted every area of society–from jobs to education to human connection– and how that impact has disproportionately affected marginalized communities.

More than 7.3 million people have been infected by the coronavirus worldwide. But the virus’s effects have been felt most severely by those living in poverty, those who are homeless, minorities, and immigrants–not only in terms of physical health, but mental and financial health as well.

“One major issue we are dealing with that directly affects our mental health is uncertainty,” said Popescu, whose work focuses on migration policies and their impact.

But for those who live in poverty or who are homeless, uncertainty was already part of their lives, she said. People living in poverty, for example, had little access to existing health services, probably suffered from preexisting conditions that were not treated properly, and faced precarious employment situations before the pandemic hit.

A Complex Emergency

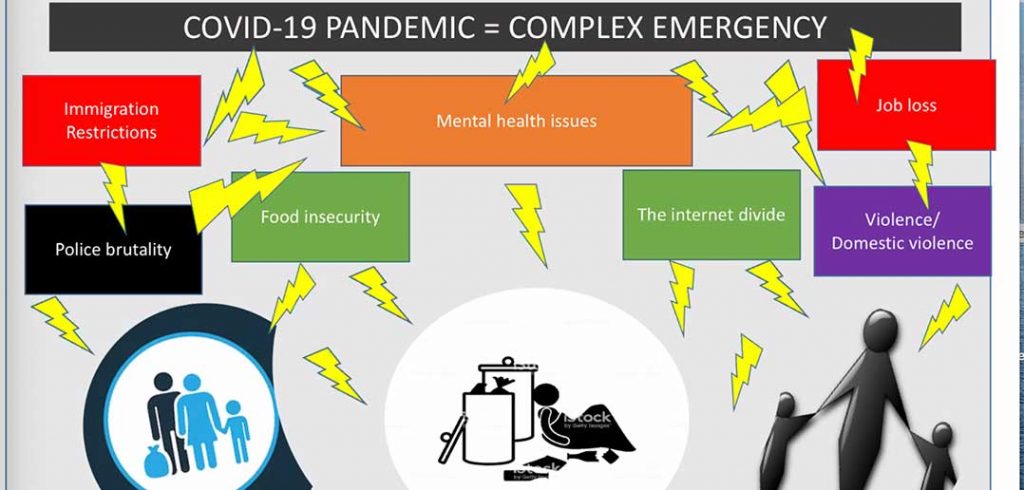

“We’re not talking about a public health crisis anymore, we are talking about a complex emergency,” she said.

In a complex emergency, preexisting issues such as mental health concerns, food insecurity, domestic violence, and the internet divide become exacerbated.

“How do you deal with food security, when you counted on the school lunches?” Popescu asked as an example.

Even some of the protections government and health officials recommended furthered divides across groups, she explained.

“When you are homeless, you don’t have access to the basic level of protection,” she said. “Where would you wash your hands? Where would you go for info? Can you access testing—do you know you can access testing?”

Even the ability to social distance or access remote education shows a person’s privilege, Popescu said.

For immigrants as well as migrants, whom Popescu referred to as “people of forced migration,” living situations often include overcrowding and multigenerational households, on top of the fact that many immigrants work in “essential jobs” and have had to continue to go to work through this crisis.

“We are dealing with all this in a context of privilege,” she said. “People might be forced to continue to work. If they lose their jobs, they have no protections in place. [Their homes are] not always safe. [There’s] little time to work and support children.”

‘People Are Losing Hope’

While their individual histories and traumas are often different, the Black community and people in communities of forced migration, particularly those from Latin America, face similar hardships.

The CDC found that in New York City, COVID-19 death rates for Black/African American people—92.3 deaths per 100,000 population, and Hispanic/Latino people—74.3, were much higher than those of both white people—45.2, or Asian people—34.5.

“Both groups were pushed to the margins,” Popescu said, citing high rates of poverty, educational quality, access to health care, and police/ICE brutality.“[We can] see all the steps we as a society took in pushing these groups further to the margins—this was to be expected.”

These communities also feel the impact of previous and current trauma that can dramatically affect their mental health. For example, she said, this generation of migrant children probably has two main experiences in life—one in their home country, living in conflict, and one of the journey of migration to the United States.

Popescu warned that people in distress from the pandemic, particularly those already dealing with depression, anxiety, and PTSD, might be susceptible to potential suicide.

“Death by despair—I’m afraid we have to prepare ourselves to deal with this because people are desperate. People are losing hope,” she said.

Popescu emphasized that it’s not enough to provide individuals with resources and put it upon them to “find help” for their mental health and other issues; it’s up to the community to support them.

Listening to Marginalized Voices

One of the first ways communities can do that is to have people in power listen to both Black and immigrant voices.

“They’re both invisible when it comes to policy—they’re not represented,” she said. “On the other hand, when anything can be used against this population, visibility increases.”

Another way to support them, she said, is to make sure they have accurate information available in an accessible format, including in their native language.

“We really need to think of the fact that engaging the people who are directly impacted—it’s one of the most important steps we need to take,” she said. “Unless you share the lived experience of the population … you’re not an expert.”