“The burden shouldn’t be placed on the child to always have to explain to the class how their family is related and why they belong together—they shouldn’t have to validate their family all the time. The school counselors and teachers should be there to create that open dialogue and sense of acceptance and community so nobody feels stigmatized, isolated or othered,” said Park-Taylor, who teaches counseling psychology and directs training for Fordham’s counseling psychology doctoral program.

A transracial adoption is when a family adopts a child of a race other than their own. Park-Taylor and Wing’s article “Microfictions and Microaggressions: Counselors’ Work With Transracial Adoptees in Schools,” published online in the Professional School Counseling journal on June 15, identifies what microaggressions and microfictions—false narratives about an adoption—might look like for transracial adoptees and their families. The article also advises school counselors on how they can work with K-12 educators to help transracial adoptees and their families.

School counselors are important because they can connect their clients with resources and families who are facing similar situations, Park-Taylor and Wing said. They can also speak directly with educators and administrators about how to make curricula more inclusive and sensitive, especially when adoption-related topics come up in class.

“When you are part of a biological family, there’s a little bit of a privilege or power associated with that because you don’t recognize what it’s like for somebody who’s not. It’s good to have school counselors and teachers become more aware of some assignments that might be triggering, hurtful, or emotionally difficult for transracial adoptees or adoptees [in general],” said Park-Taylor.

Dealing With Microaggressions and Microfictions

Park-Taylor and Wing’s article is divided into three sections: an overview of transracial adoptee population trends, a case illustration about a fictional transracial adoptee student whose experiences are informed by real-life narratives, and recommendations for school counselors working with transracial adoptees.

The last section focuses on how common school assignments could hurt transracial adoptees, especially those who are adopted outside of the U.S.

“At the elementary level, family trees, developmental timelines, and bringing in your baby photo are all very triggering assignments. In middle school and high school, genetics projects serve as reminders to adoptees that their biological history is often unknown, and for assignments where students are asked to learn about other countries, transracial adoptees may feel pressured to pick their birth country as the only option, which can further heighten their sense of racial difference and othering,” Wing said in a Fordham News interview.

Students also face microaggressions from their peers, including the phrase “Go back to your country.” Their article can help school counselors identify microaggressions and intervene in situations at school, said Park-Taylor and Wing.

“It’s not just the sole responsibility of the adoptee to educate other people, especially if they don’t have the language at that time of their age or development, or the awareness themselves,” said Wing.

Another microaggression is a “microfiction” in the family home—when adoption stories are intentionally altered or replaced with fictional ones that “sugarcoat everything to this beautiful, picture-perfect experience,” Park-Taylor said.

“That can neglect the complexity and oversimplify the experiences adoptees might have. They may feel like there isn’t really space for them to talk about the more negative aspects in conjunction with the positive ones, so they feel more isolated,” Wing added. “If they can’t talk about that in their families, where can they talk about it?”

A Personal Connection

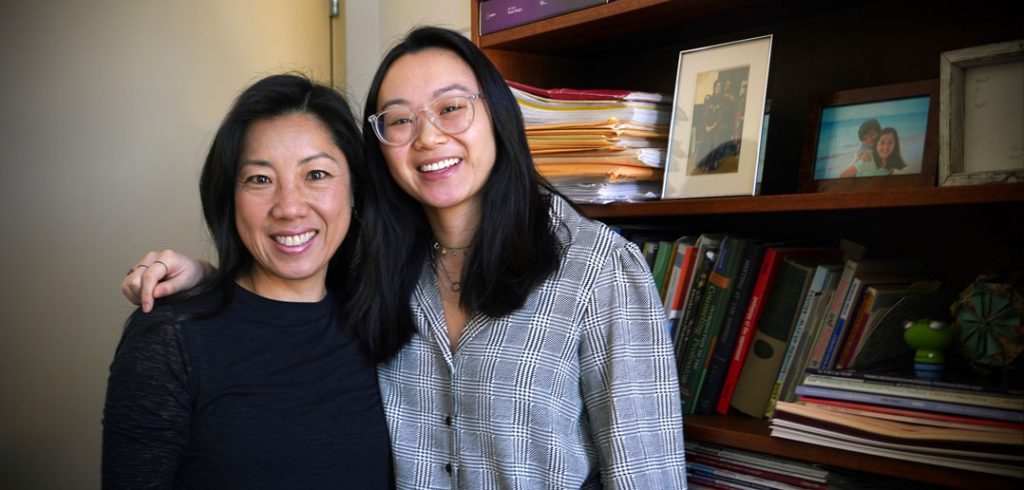

For Wing, a transracial adoptee from China, the topic hits close to home.

When she was a child, people asked her intrusive questions. One of them was, “Who are your real parents?”

“Having to, as a child, validate your connection with people who you’re connected to and have raised you most of your life, if not all of it … It’s a lot of weight to put on a child’s shoulders,” Wing said.

Today, she is a young adult. But those microaggressions haven’t stopped—especially when people learn that Wing is an adoptee.

“Usually, the first response I get is, have you searched for your birth parents? Do you have connections with them? There’s an automatic assumption that A, I have a desire to. B—”

“—that you’re supposed to, somehow,” Park-Taylor chimed in.

“Yeah. Or even that I have access to that. For a lot of international adoptees, in particular, that isn’t a possibility,” Wing said.

Her research on this article over the past year has helped her understand how useful these recommendations might have been when she was younger, she said.

“School counselors weren’t really a force or presence in my life. The suggestions that we give are ones that I might’ve wished for myself or other people who are currently at younger stages of development, when it’s more difficult to process these feelings of confusion or stigmatization,” said Wing, a group facilitator for Families with Children from China and recently appointed Student Representative for the Adoption Research and Practice Special Interest Group in the American Psychological Association. But things are starting to change.

“There’s been a larger push for multiculturalism and more socially just interventions and approaches in counseling psychology and larger fields of psychology, but somehow, I feel like transracial adoption is missed in that pool,” said Wing, who is now planning a project with Park-Taylor that focuses on supporting transracial adoptive parents, particularly amid the current pandemic and recent rise in xenophobia against Asian Americans. “I think this begins to open up the way in which we conceptualize giving that space.”