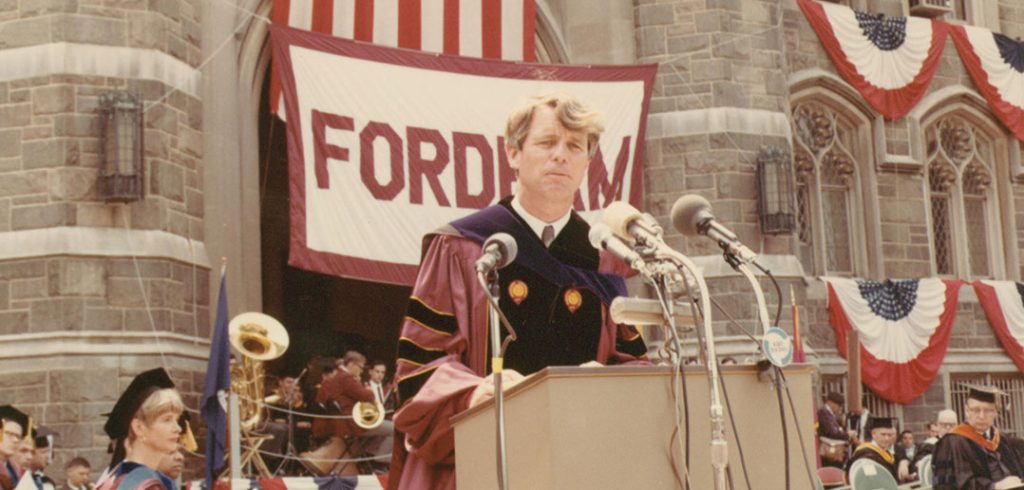

On June 10, 1967—a time of mass protests against the Vietnam war and rising violence in the struggle for racial justice—the 41-year-old U.S. senator from New York reminded Fordham graduates that they were entering “a world aflame with the desires and hatreds of multitudes.”

He urged them to hear the voices of “the dispossessed, the insulted, and injured of the globe,” to heed their own revolutionary responsibilities, and to remember the difference that one person can make. And he quoted from his June 1966 “Day of Affirmation” address at the University of Cape Town during the height of apartheid in South Africa:

Each time a man stands up for an ideal, or acts to improve the lot of others, or strikes out against injustice, he sends forth a tiny ripple of hope, and crossing each other from a million different centers of energy and daring, those ripples build a current which can sweep down the mightiest walls of oppression and resistance.

“It was electrifying,” recalls William Arnone, FCRH ’70, who heard the speech from the back of Edwards Parade. Later that year, Kennedy’s staff came to Fordham to recruit students. “They said, ‘You can study politics or you can do it,’” Arnone says. “Next day, I showed up. I was hooked.”

He and several other Fordham undergraduates worked as constituent case aides in the senator’s New York office, fielding inquiries from New Yorkers in distress.

In the four-part Netflix series Bobby Kennedy for President, released last year, Arnone describes taking calls from single mothers in Harlem who struggled to protect their children from rats—and to get their landlord to help.

“I would get the name of the superintendent and the landlord,” Arnone says in the film, “and I would call them up: ‘This is William Arnone, I’m calling on behalf of Senator Robert F. Kennedy. There are rats in Mrs. Smith’s apartment, eating her children’s toes. What are you going to do about it?’ And I would get the same answer, ‘You mean Robert Kennedy cares about Mrs. Smith’s kids?’ ‘Yes.’

“I would get the name of the superintendent and the landlord,” Arnone says in the film, “and I would call them up: ‘This is William Arnone, I’m calling on behalf of Senator Robert F. Kennedy. There are rats in Mrs. Smith’s apartment, eating her children’s toes. What are you going to do about it?’ And I would get the same answer, ‘You mean Robert Kennedy cares about Mrs. Smith’s kids?’ ‘Yes.’

“Invariably I get a call the next day: They have an exterminator, no more rats. ‘Thank God for Mr. Kennedy.’”

In mid-March 1968, Kennedy launched his campaign for president, running on a platform of economic and racial justice, and an end to the war in Vietnam. “We all fed him things to use in the campaign,” recalls Arnone, who was ecstatic when Kennedy shared his story about the rats during a campaign speech. “But then he would send me notes and say, ‘Good job, you helped her. But we have to have the solution that’s systemic.’”

Kennedy’s campaign lasted less than 90 days. Shortly after winning the California primary, he was assassinated in the kitchen of the Ambassador Hotel in Los Angeles. He died on June 6.

Two days later, Arnone was at St. Patrick’s Cathedral in Manhattan for Kennedy’s funeral Mass, after which he rode on the private train that carried Kennedy’s body from New York City to Washington, D.C., for burial in Arlington National Cemetery.

“It was just a nightmare, but it was poignant” seeing the hundreds of thousands of mourners who lined the tracks to bid Kennedy farewell, he said.

Arnone went on to a career focused on the elderly and retirement issues. He is the chief executive of the National Academy of Social Insurance, a Washington, D.C.-based nonpartisan think tank, and he remains inspired by Kennedy.

“He was fierce, passionate, and understood vulnerability in a way that was authentic, and it changed my life. His whole goal was to bring people together and try to avoid class warfare, avoid violence,” Arnone says. “To me, that’s the message for today.”