“The history of botany, and the study of plants, transpires in Latin,” Matthew McGowan, Ph.D., an associate professor of classics at Fordham, told the tour group, explaining how his own area of expertise led to his interest in botany.

It was the latest of many field trips McGowan has organized over the years to show where Latin persists in the modern world. He has led trips to the Morgan Library and the Metropolitan Museum of Art, in addition to the botanical garden, which houses nearly 8 million samples of plant species—the world’s second-largest collection—across the street from Fordham’s Rose Hill campus.

McGowan first connected with the garden and its experts in 2007; two of them co-led the tour. “I recognized when I arrived at Fordham 13 years ago that botany and the science of botany was the only discipline that I could determine where a knowledge of Latin and publishing in Latin was absolutely necessary,” he said at the outset of the tour, speaking to approximately 40 alumni and students in front of the garden’s LuEsther T. Mertz Library.

The tour began with stories of innovators from ages past. Its first stop was the library’s Rare Books Room, with its centuries-old copies of works by naturalists including Carl Linnaeus, the 18th-century Swiss physician and horticulturalist known as the father of modern taxonomy.

“He wasn’t the first to come up with a system for organizing the plant world, but his was the first to stick, and be universally accepted,” said Stephen Sinon, the William B. O’Connor Curator of Special Collections, Research and Archives at the botanical garden. Linnaeus synthesized and collated existing names, and “Latin was the basis of his system,” Sinon said. “As a dead language, it could be universally accepted, and wouldn’t change as a living language would.”

Linnaeus’ two-word designations replaced wordier names, incorporating descriptions of the species that could run to more than a dozen words, said Robbin Moran, Ph.D., the Nathaniel Lord Britton Curator of Botany at the botanical garden. “Imagine trying to utter that every time you wanted to refer to a species,” Moran said.

For example, he said, the formal name of the agave plant was Agave foliis spinoso-dentatis mucronatisque (“Agave with leaves spinose-dentate and with a sharp-pointed tip”). Linnaeus provided an alternative for these long names—in this case, simply Agave americana.

McGowan noted that some plant names also contain words from other languages, including Greek and English, that have been “Latinized” for the sake of consistency.

A Dash of Controversy

Linnaeus developed his classification system in Species Plantarum—an original copy of which the alumni and students perused in the Rare Books Room—and an earlier work, Systema Naturae, with its sexual classification system that proved controversial, Moran said. Linnaeus based his classification on flowers, which he likened to a marriage: the flower’s pollen-producing stamens were the husbands and seed- and fruit-producing pistils were the wives. If a plant had, say, one pistil and six stamens, Linnaeus described it as having “six husbands and one wife in the marriage,” Moran said. Many of Linnaeus’ colleagues thought this scandalous, leading to some of his books being banned in parts of Europe, Moran said.

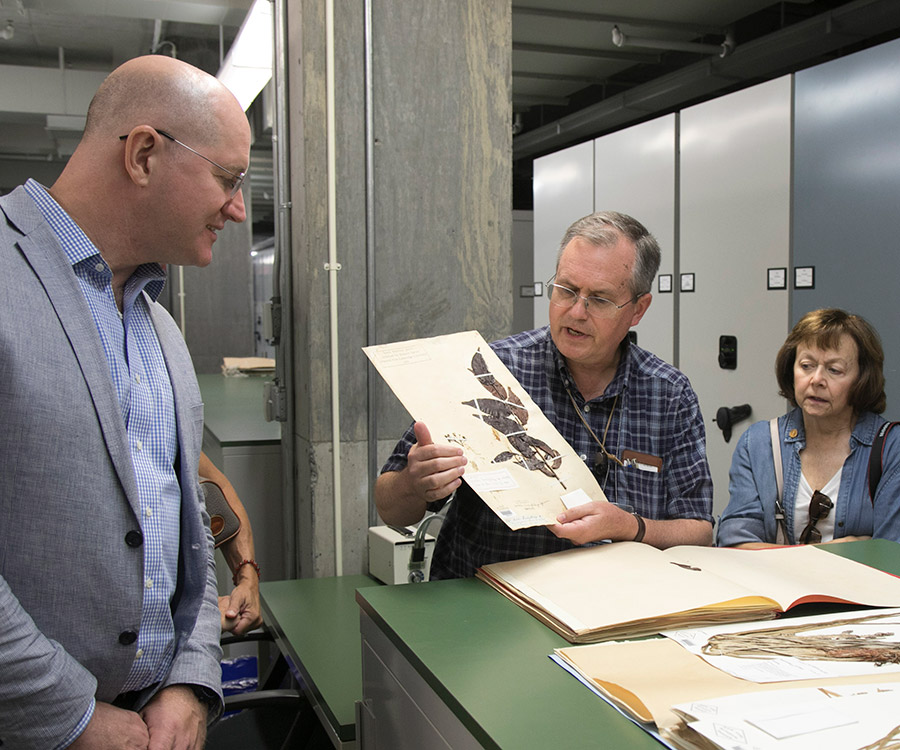

After perusing the rare books and their detailed, ornate illustrations of plants, the group moved to the William and Lynda Steere Herbarium. Moran showed plant specimens and described their two-word names that incorporate genus and species, like Hirtella brachystachya, a South American plant whose short stem is reflected in its name, McGowan said.

Moran pointed out that when new species of plants were named, they were often accompanied by lengthier descriptions, also written in Latin. He noted that the International Code of Nomenclature for Algae, Fungi, and Plants no longer requires Latin for formal descriptions of new species. English has been allowed since 2012, in part to make species identification more efficient and stay ahead of extinction threats.

Turning the Page on Latin

Botanists still need to know Latin for the sake of reading older literature and composing names for new species, Moran said. McGowan said the move away from Latin descriptions “was probably inevitable, and need not be the cause for excessive lament.”

“What was originally meant to universalize the science of botany and simplify communication across the globe had in fact become a hindrance to actual botanists practicing their art in the face of other more pressing threats, like the disappearance of plant species due to climate change and deforestation,” he said.

“Latin is obviously still crucial for a genuine knowledge of botanical history and, more generally, of the history of science,” he said.

One attendee, Susan Snyder, FCRH ’86, a retired teacher, was amazed to learn about the medicinal use of plants in centuries past. “It made me worry, too … that we’re going to lose a lot of plants that could be medicines,” she said.

Another alumna, Mary Guardiani, UGE ’62, GSE ’92, also enjoyed the deep and wide-ranging presentation: “It was thoroughly enjoyable, because the presenters knew the topic intimately.”

The tour of the New York Botanical Garden was one of many cultural events regularly held in the New York area and around the country by Fordham’s Office of Alumni Relations. Upcoming events include museum tours, concerts, and theater performances, and more.