As senior exhibition designer at New York City’s Metropolitan Museum of Art, Fordham grad Fabiana Weinberg plays a big role in how visitors experience—and engage with—the works on display.

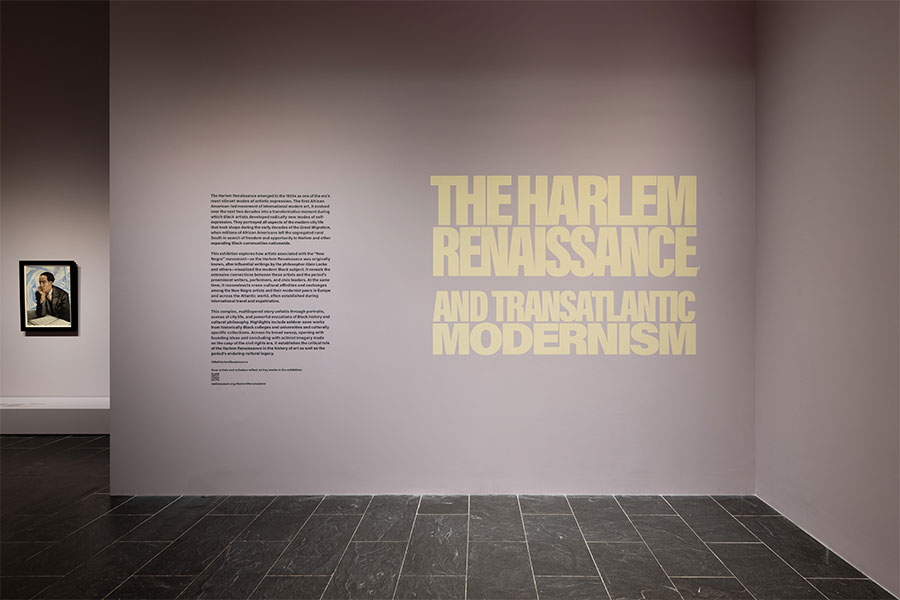

If you walk through the “Harlem Renaissance and Transatlantic Modernism” exhibit at the Metropolitan Museum of Art—on view through July 28—you might be struck by many paintings and sculptures in their own right. But as you pass from gallery to gallery, you may also feel like you’re being guided through a conversation with everything you see.

That kind of conversation—between works of art and viewers—is one that Fabiana Weinberg, FCLC ’07, hopes to facilitate in her role as senior exhibition designer at the Met.

“For me, it’s always a question of how do you breathe new life into these things every single time and provide the space for a dialogue with them?” Weinberg says. “I like the permanence of material culture, but also the ability to constantly think about it and marinate on it.”

The Harlem Renaissance exhibit gives people plenty to think about, including how to bring a “still-neglected art history out of the wings and onto the main stage,” as New York Times critic Holland Carter put it. The exhibit does that by featuring Black American artists from the 1920s to the 1940s like William H. Johnson, Laura Wheeler Waring, and Aaron Douglas—whose 1934 large-scale painting, Aspects of Negro Life: From Slavery Through Reconstruction, inspired the soft color palette for the gallery walls—along with portrayals of the African diaspora by European artists like Henri Matisse, Edvard Munch, and Pablo Picasso.

“This show is really exciting because there are a lot of paintings but also ephemera and magazines and books and sculpture,” Weinberg says. “It’s a really immersive experience going through the galleries. A lot of these works are on view for the first time, and it’s really about expanding the canon.”

Weinberg majored in visual arts and art history at Fordham College at Lincoln Center, and after graduating in 2007, she earned a master’s degree in architecture from the Rhode Island School of Design. She uses all that academic training to think broadly about the aesthetic and design choices that go into museum exhibits—from sketching design ideas, to using 3D-rendering software to move pieces of art around in a virtual replica of a gallery, to collaborating with tradespeople to build out the physical walls and cases and with curators to decide how to best showcase their selected works.

Her way of thinking about how people engage with art, though, began much earlier.

An Artistic Childhood and an Ideas-Driven Education

Weinberg grew up on Manhattan’s Upper West Side. As a kid, she trained to be a dancer, and her parents—a mother who was a photographer and a Fordham grad and a businessman father who became a high school teacher after earning a Fordham degree—frequently brought her to museums and exposed her to a wide range of performing arts.

At Fordham, she initially focused on natural sciences, but something clicked when she took an art history course—she decided to change majors. She says that Fordham’s core curriculum also gave her a foundation that added texture to her studies. “One thing I really always liked about Fordham’s approach is it was always ideas-driven, like, ‘What are you trying to say? What are you trying to do?’ And what it looks like—that comes later.”

After finishing her master’s in 2012, Weinberg moved back to New York and worked a variety of jobs across the design landscape, from scenic design to lighting design. The following year, she saw a posting for an exhibition designer position at the Rubin Museum of Art in Chelsea. Although she had no experience in exhibition design, she heard back from the Rubin’s head of design, John Monaco, a former sculptor who saw promise in her application. She went on to spend four years at the Rubin before moving on to the Met in 2017.

‘Every Single Thing is a Decision’

In her time at the Met, Weinberg has designed or co-designed several premier shows, including 2020’s “Making the Met,” which looked back at the institution’s 150-year history; 2021’s Alice Neel retrospective; and “Before Yesterday We Could Fly,” an Afrofuturist period room that opened in 2021 and remains on display.

Last December, she gave a group of Fordham alumni a private, behind-the-scenes look at “Africa & Byzantium,” which highlighted the artistic connections between these two geographically distant ancient civilizations. Before seeing the exhibit, which was darkly lit and made use of striking gold wall text, the alumni gathered in a conference room in the museum’s design department, where Weinberg demonstrated the Vectorworks 3D design software she and her colleagues use to plan out exhibitions.

“There’s still nothing like having a drawing that you see in your mind and then spatialize in a 3D model and then go into the gallery and see it being built,” she says of the work. “It’s thrilling.”

For the Harlem Renaissance exhibit, Weinberg says she tried to give viewers a sense of scale from room to room—and offer a contrast between some of the more esoteric written pieces on display and other sections with bursts of color and city life.

“At the beginning,” she explains, “there’s an introduction to the thinkers of the time, and we really wanted to create intimacy with these figures that really set the stage for what you’re going to see later. And then we have another gallery about city life that we wanted to open up. … So, using paint color and proportions of the space and dimensions, [we] give those different senses of scale between the intimacy of more domestic spaces and then more open, larger spaces.”

Weinberg says the breadth of her experience—from childhood museum visits to her understanding of space through dance—has helped her develop her eye for design. And while museum exhibition design wasn’t something she consciously thought about on all those childhood trips, it’s now front of mind for her. “When I go to museums, I can’t unsee how the spaces are designed,” she says. “Every single thing is a decision.”