On Dec. 2 in Manhattan, a first edition of Underworld, the 1997 novel by acclaimed author Don DeLillo, FCRH ’58, sold at auction for $57,000.

On Dec. 2 in Manhattan, a first edition of Underworld, the 1997 novel by acclaimed author Don DeLillo, FCRH ’58, sold at auction for $57,000.

It was no ordinary first edition of the book.

Earlier this year, DeLillo spent several days revisiting the novel. He made handwritten notes on nearly half of the book’s 800-plus pages, commenting on characters and themes and his creative process.

The auction, hosted by Christie’s New York, featured 74 other well-known books annotated by their authors.

Called “First Editions/Second Thoughts,” the benefit raised $1 million for PEN American Center, the largest branch of PEN International, which promotes literature and freedom of expression.

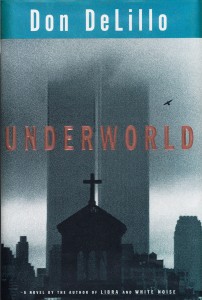

DeLillo’s copy of Underworld—with its original cover featuring Andre Kertész’s iconic image of the Twin Towers, a church in the foreground and a lone bird flying near the buildings—brought in the second-highest bid of the evening. (Only one other work, Phillip Roth’s American Pastoral, with a winning bid of $80,000, raised more money for PEN.)

DeLillo’s copy of Underworld—with its original cover featuring Andre Kertész’s iconic image of the Twin Towers, a church in the foreground and a lone bird flying near the buildings—brought in the second-highest bid of the evening. (Only one other work, Phillip Roth’s American Pastoral, with a winning bid of $80,000, raised more money for PEN.)

For years, DeLillo has participated in PEN-sponsored public readings to raise awareness of human rights abuses and help persecuted writers throughout the world speak truth to power.

“Writers who are subjected to state censorship, threatened with imprisonment, or menaced by violent forces in their society,” he said in a 2010 interview, “clearly merit the support of those of us who enjoy freedom of expression.”

The Shots Heard Round the World

DeLillo’s magnum opus opens with a bang—two bangs, actually, both based on actual events.

DeLillo’s magnum opus opens with a bang—two bangs, actually, both based on actual events.

At the Polo Grounds in Manhattan on Oct. 3, 1951, Bobby Thomson hits a home run to help the New York Giants win the National League pennant. The game-winning blast is dubbed the Shot Heard Round the World.

Meanwhile, on the same October day, the U.S. government learns that the Soviet Union has successfully tested an atomic bomb.

The two events are fused in the novel through a fictionalized version of J. Edgar Hoover, real-life director of the FBI, who was at the Polo Grounds that day.

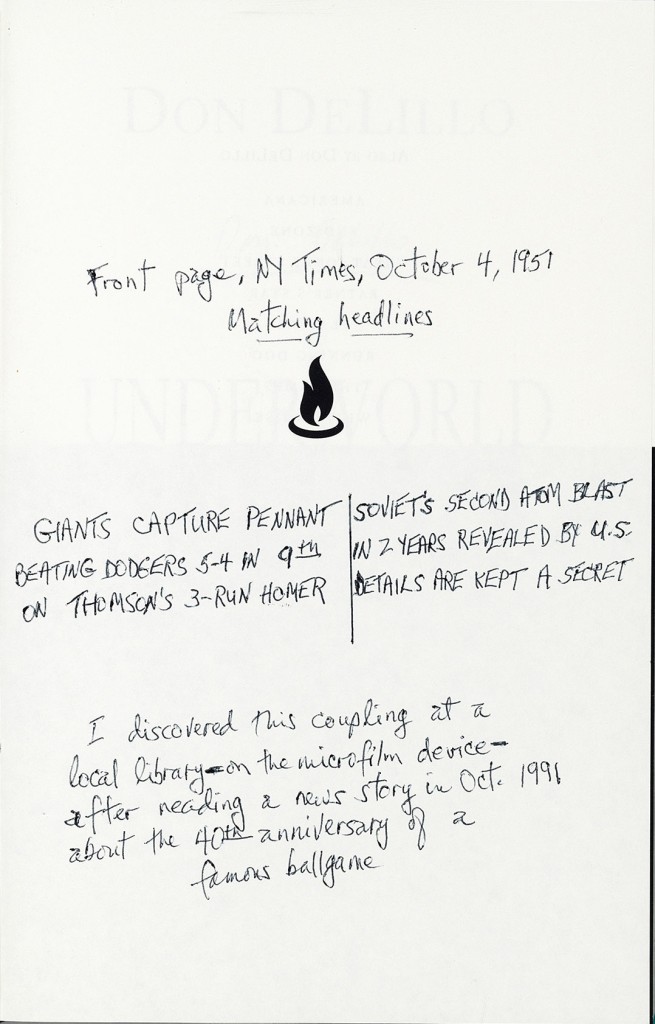

In one of his notes on the book, DeLillo describes the front page of the October 4, 1951, edition of The New York Times, which featured matching headlines about the dramatic game and the atomic bomb test, each headline the same size, in the same typeface.

“I discovered this coupling at a local library—on the microfilm device—while reading a news story in Oct. 1991 on the 40th anniversary of a famous ballgame,” DeLillo writes.

The juxtaposition fired his imagination. He once told an interviewer that he felt the events marked a “transitional moment” in American history, a change in the tenor of the times.

“The ballgame was a unifying and largely joyous event, the kind of event in which people come out of their houses in order to share their feelings with others. … With the onset of the bomb, the communal spirit becomes associated with danger and loss rather than celebration,” he said.

“And the sense of catastrophic events, framed and defined by TV, grows ever stronger: assassinations, terrorist acts, even natural disasters.”

An Underground History, Five Years in the Making

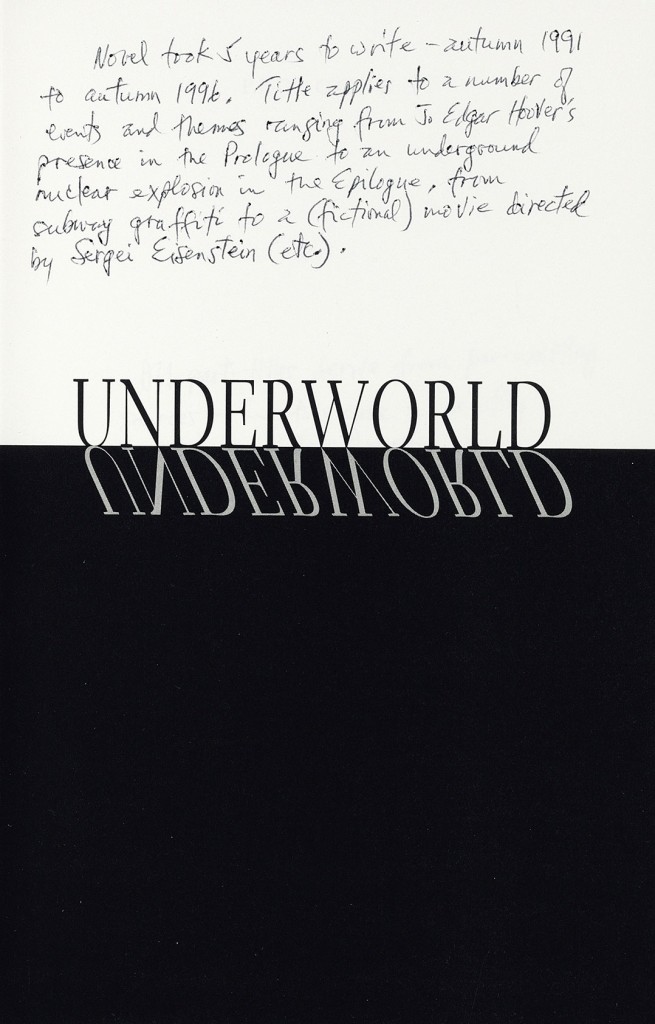

In a note on the book’s title page, DeLillo explains why he called the novel Underworld. “Title applies to a number of events and themes ranging from J. Edgar Hoover’s presence in the Prologue to an underground nuclear explosion in the Epilogue,” he writes, “from subway graffiti to a (fictional) movie directed by Sergei Eisenstein (etc.).”

In a note on the book’s title page, DeLillo explains why he called the novel Underworld. “Title applies to a number of events and themes ranging from J. Edgar Hoover’s presence in the Prologue to an underground nuclear explosion in the Epilogue,” he writes, “from subway graffiti to a (fictional) movie directed by Sergei Eisenstein (etc.).”

After the prologue, the novel jumps to Arizona in the early 1990s and introduces one of the book’s central characters, middle-aged Nick Shay, a waste-management executive with a deeply troubled past.

When Nick was 11 years old, growing up in the Bronx, his father went out to buy Lucky Strike cigarettes and never returned home. Nick imagines that his dad, a small-time bookie, was whacked by the mob. And his young life becomes defined by his father’s absence and an ever-present sense of violence.

The narrative of Underworld moves backward in time, from the 1990s toward a reckoning with the day—Oct. 4, 1951—when a 17-year-old Nick kills someone. He serves time in a juvenile correctional facility and is later sent to a Jesuit reform school before establishing a more stable, middle-class life for himself.

Throughout the novel, Nick and various other characters reckon with historical events and cultural forces that shaped the second half of the 20th century: the rise of the Internet and global capitalism, nuclear proliferation and waste, the construction of the Twin Towers, the Vietnam War, rock and roll, the ’60s counterculture, and the Cuban Missile Crisis, among others.

DeLillo’s Bronx, Jesuit Roots

Like the fictional Nick Shay, DeLillo grew up in the Belmont section of the Bronx, a stone’s throw from Fordham’s Rose Hill campus.

In some of his notes on the book, he calls attention to the parts of Underworld that were drawn from his own experiences.

“I didn’t realize until now,” he writes on one page, “that there was so much of the Bronx in this novel.”

DeLillo, who earned a bachelor’s degree at Fordham in 1958, recently told an interviewer that he felt he was “the only guy in America who walked to college.” On another occasion, years ago, he said that at Fordham “the Jesuits taught me to be a failed ascetic.”

The University is mentioned a few times in Underworld, and there’s even a fictional Jesuit, Andrew Paulus, S.J., who holds “a chair in the humanities at Fordham” and later instructs Nick at a Jesuit reform school in Minnesota.

In one scene, a Bronx high school teacher tries to persuade Father Paulus to talk with Nick, then a 16-year-old boy he describes as bright “‘but lazy and unmotivated.’”

“‘I’m speaking on behalf of the mother now,’” the teacher says to the priest. “‘She wondered if you’d be willing to spend an hour with him. Tell him about Fordham. What college might offer such a boy. What the Jesuits offer.”

At the reform school, Father Paulus introduces Nick to the word quotidian, calling it “an extraordinary word that suggests the depth and reach of the commonplace.”

As an adult, Nick reflects on the education he received and how it shaped his life and career. “The Jesuits,” he says, “taught me to examine things for second meanings and deeper connections.”

“He speaks in your voice, American … ”

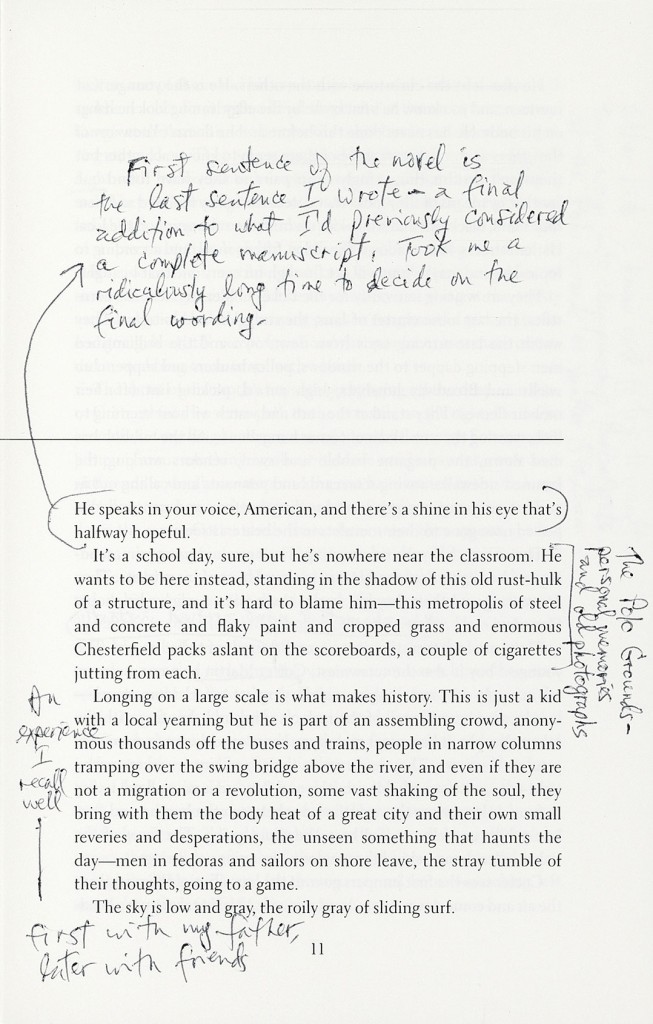

The first sentence of Underworld was the last one that DeLillo wrote for the novel. In his notes, he refers to it as “a final addition to what I’d previously considered a complete manuscript.”

The first sentence of Underworld was the last one that DeLillo wrote for the novel. In his notes, he refers to it as “a final addition to what I’d previously considered a complete manuscript.”

The reference to an American voice calls to mind the title of DeLillo’s first novel, Americana, and his stature as one of the country’s most celebrated literary voices.

In September 2013, more than 40 years after he published his first novel, he received the inaugural Library of Congress Prize for American Fiction.

The award “seeks to commend strong, unique, enduring voices that—throughout long, consistently accomplished careers—have told us something about the American experience.”