A look at the true causes and costs of prison growth—and how education and spiritual direction can help break the cycle of incarceration

With just 5% of the world’s people but more than 20% of its prison and jail inmates, the United States clearly has an incarceration problem—and experts say it will take far more than federal legislation to truly fix it.

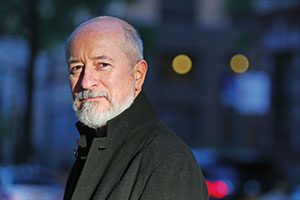

“Mass incarceration is not just a huge policy failure. It’s a humanity failure,” says John Pfaff, Ph.D., a professor at Fordham Law School and author of Locked In: The True Causes of Mass Incarceration and How to Achieve Real Reform (Basic Books, 2017).

Pfaff has shifted the debate about criminal justice reform by challenging the standard story about the runaway growth of the U.S. prison population since the early 1970s. The primary cause, he argues, is not the war on drugs and the proliferation of nonviolent offenders in prison but the unchecked power of local prosecutors and how we respond to violent crime.

Part of the solution is to give prosecutors incentives and tools to take a less punitive approach, Pfaff says. He has also called for more public consideration of the prison system’s impact on people and communities. “We spend $50 billion a year on running the prison system,” he says. “But we can’t tell you what we’re really spending in terms of the actual human costs.”

In prison, people contract diseases like HIV and tuberculosis at a rate 10 to 100 times higher than outside the prison system, he says. They suffer physical and sexual abuse, develop mental health problems, and have a hard time earning enough money when they’re released. Their families earn less and suffer from mental health trauma as well, and their children face a greater risk of going to prison. “And despite doing this for 40 years,” he says, “we’ve just never estimated those costs, and I think we haven’t measured them, because at a very real level, we don’t care.”

A change in attitudes is needed, he says. “How do you get people who aren’t in the prison system to care about those who are? Until we make that move, we’re going to really struggle to not be the world’s largest jailer.”

Prevention Before Incarceration

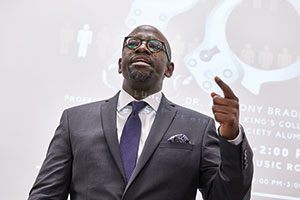

Like Pfaff, Anthony Bradley, Ph.D., GSAS ’13, decries overly punitive approaches to criminal justice, and points to a host of additional causes of mass incarceration: class, poverty, race, family breakdown, and mental illness.

In his book Ending Overcriminalization and Mass Incarceration: Hope from Civil Society (Cambridge University Press, 2018), he argues for taking a comprehensive, long-term approach to safeguarding the well-being of people who are at a higher risk of getting in trouble with the law. Everyone can help in this effort, he says. “This is largely an issue about who we decide has human dignity and who does not.”

During a lecture at Fordham’s Rose Hill campus last November, he explained that the book had its beginnings in a class he took while earning a master’s degree in ethics and society at Fordham. He was “blown away,” he said, after learning about the links between young children developing post-traumatic stress disorder and ending up in the juvenile justice system later on.

“I realized that we’re not just locking up bad kids, we’re locking up hurt kids. It completely changed the course of my career,” said Bradley, a professor of religious studies and director of the Center for the Study of Human Flourishing at The King’s College in Manhattan.

The federal government’s war on drugs since the early 1970s can’t be the main cause of mass incarceration, he said, because 90% of all inmates are in state prisons, and of those, only 17% are drug offenders. In part because of a focus on federal prison data, “we get the story wrong,” he said. “If we don’t get the story right, we’ll get the solutions and interventions wrong.”

Part of that story, he said, is society’s views toward the poor. “Here’s a tough social fact in this country: We resent poor people in America regardless of their race,” he said. “We’ve used the criminal justice system to remove them, the poor, from civil society.”

And those who enter the criminal justice system are “overwhelmingly poor,” he added. With no money to pay legal bills, they have to rely on overburdened public defenders, and their poverty is compounded when their prison records create a barrier to employment, he said.

Caring for the Whole Person

Last December, the federal government enacted the First Step Act to reform criminal justice and reduce prison crowding, following on many state governments’ legislative efforts over the past decade.

While the new law is commendable, deep and meaningful change can only come from convincing the nation’s local prosecutors and police chiefs to do things differently, Pfaff says. “We tend to focus on the federal government as what is going to fix the problem,” but solutions must come on a “city-by-city, county-by-county level.”

In his talk at Rose Hill, Bradley also called for grassroots, “upstream” efforts to provide emotional, social, psychological, and moral support to children before they wind up in trouble with police.

“As long as we have hurting children, we’re going to have violent children,” he said. “We need to invite more players to the table. Yes, we need lawyers; yes, we need judges. … We also need coaches and teachers and business owners and cousins and aunts and uncles and community nonprofit leaders to offer the sorts of interventions that address the whole person.”

Bringing Ignatian Spirituality to the Incarcerated

Public defender John Booth, GRE ’14, has taken an interdisciplinary approach to the problem. After a decade representing people charged with serious crimes in Hudson County, New Jersey, he felt he was burning out, tired of watching clients repeat the cycle of incarceration.

“Why do I find myself representing the children of former clients?” he wondered. “When will all of this hurt end? Most importantly, where is God in all of this and why am I a witness to such horror?” He examined his own motives for becoming a public defender. “I knew I cared for them and was always fighting for them,” he says, “but I didn’t realize just how deeply they had touched me.”

Booth recognized there was a spiritual element to addressing the problems of criminality, mass incarceration, and recidivism. But there were limits to what he could do as a lawyer, ethically and practically. He knew it was inappropriate to discuss matters of faith with his clients, that “melding the roles of attorney and minister can add another injustice upon the accused person,” as he put it, but he also had no plans to give up his day job.

So in 2009, after he and his wife lost a child to stillbirth, Booth began further exploring his Catholic faith. He took “the Ignatian retreat in daily life,” a way to complete the 500-year-old Spiritual Exercises of St. Ignatius Loyola over a period of eight months instead of during an intensive 30- day retreat in solitude. Afterward, he felt that undertaking the Spiritual Exercises—a mix of meditations, prayers, and contemplative practices—could prove as valuable a healing process to incarcerated people as it was to him.

That thinking led him to Fordham’s Graduate School of Religion and Religious Education, where he completed a master’s degree in religious education in 2014. His thesis explored how the exercises could provide emotional support and spiritual freedom to inmates and help them transition to society after release.

“A lot of [inmates]will say that they can’t do this on their own,” he says.

Bringing Guidance Behind Prison Walls

After completing his master’s degree, Booth met Zach Presutti, S.J., a Jesuit scholastic and a psychotherapist with an interest in prison ministry. Presutti read Booth’s thesis and realized it contained the kind of spiritual guidance he wanted his new nonprofit, Thrive for Life Prison Project, to provide for the incarcerated.

Booth created a brochure for Thrive for Life volunteers providing Ignatian spiritual direction to inmates—and he began volunteering with the group as a spiritual director. Several times a month, he visits with inmates in New York—at Sing Sing Correctional Facility in Ossining, the State Correctional Institution in Otisville, and the Manhattan Detention Complex, also known as the Tombs—and leads them through an abridged version of the Spiritual Exercises, providing a safe environment that fosters self-expression.

“They can just kind of let go and be themselves,” he says. “And as time goes on, you see them expressing more and more and more, individually and collectively.”

Breaking the Cycle, Building Relationships

Thrive for Life’s spiritual directors stay in touch with the group’s participants. One former inmate now works full time with the group. Many other former inmates gather once a month with volunteers, friends, and family at the Church of St. Francis Xavier in Manhattan, where the organization is based. And Thrive for Life recently opened Ignacio House, a Bronx residence for people recently released from prison.

Meanwhile, Booth says his workload as a public defender was made more manageable by bail reforms New Jersey instituted two years ago, which include new standards for deciding whether an inmate poses a danger to society. His time at Fordham gave him new perspective on his day job—and on practicing his faith in service of others. “Courses were geared toward trying to live out your faith in the modern world, with constant interaction with the real world,” Booth says. “Fordham made me into the best spiritual director that I could be.”

College in a Maximum Security Prison

Since 2015, Steve Romagnoli, FCRH ’82, a playwright, novelist, and adjunct professor of English at Fordham, has been helping to bring the transformative power of education to women in prison. On a Thursday evening near the end of the spring semester, he led his students through the moral ambiguities of Ruined, Lynn Nottage’s 2009 Pulitzer Prize-winning play about the wages of war in the Democratic Republic of Congo. The scene in the classroom was reminiscent of an undergraduate seminar on any college campus, with one exception: Students wore the green uniform of inmates at Bedford Hills Correctional Facility, the only maximum security women’s prison in New York state.

Like all guests at the prison, Romagnoli enters the compound through a trailer-like structure that separates the visitors’ parking lot from the prison buildings, which are ringed by metal gates topped with razor-wire coils. He passes through a security checkpoint carrying only his car keys, driver’s license, and notes for class.

“It’s like going in and out of a concentration camp, with the walls and the wires,” he says. “But sitting in the room and watching them talk and laugh and banter, you could be anywhere.”

Romagnoli’s students range in age and experience. For one woman, the course—Social Issues in Literature—is her first taste of college; for another, it’s the next-to-last class needed for her bachelor’s degree in sociology.

“Steve is always in demand,” says Aileen Baumgartner, FCRH ’88, GSAS ’90, the director of the Bedford Hills College Program. Overseen by Marymount Manhattan College, it offers courses leading to an associate’s degree in social sciences and a bachelor’s degree in sociology.

“Students really get a lot from his classes. I don’t know how he does it—I’ve said, ‘Really, Steve? You think they’re going to get through all this in a semester?’ Somehow or other they do.”

‘Students Have to Feel There Is Love’

At Fordham, Romagnoli teaches a similar course on ethics and literature, albeit with a more sensational title: Murder, Mayhem, and Madness. In both settings, students focus on “moral dilemmas and ethical questions that confront us throughout our lives,” he says.

“The Fordham students have great things to say, but they’re initially a bit shy,” he says. “At the prison, sometimes you’ve got to pull them together, but they’re totally engaged, and they say what they’ve got to say.”

Romagnoli began his career as an educator at P.S. 26 in the South Bronx during the mid-1980s, not long after earning a bachelor’s degree in English at Fordham. He later earned an M.F.A. in creative writing at the City College of New York.

For 15 years, he was an itinerant teacher for the New York City Department of Education, working with students in their late teens to early 20s at drug rehabilitation facilities, homeless shelters, and halfway houses, among other locations. “I would go in and teach a lesson and go out,” he says. “Engage them, that was the whole thing. You’ve got to engage them.”

No matter where he teaches, his approach is essentially the same. “Students have to feel there is love there—not love love, but a deep respect. And if they come to the conclusion, consciously or unconsciously, that you have that deep respect, then it allows you to be as demanding as you want to be.”

Baumgartner notes that all of the students at Bedford Hills are required to work during the day—as porters or clerks or sweeping floors, for example. And they complete their coursework in the evening and early morning hours without the benefit of internet access.

Like Romagnoli, Baumgartner went to Fordham, where she earned bachelor’s and master’s degrees in English. She started teaching at Bedford Hills in 2001, when she was a professor at Mercy College, and became the director of the college program in 2002.

“I had never given any thought to prison education programs,” she says. She recalled that on her first day of class, “all the students were looking at me, sizing me up, and they asked, ‘Why are you here?’ ‘I was asked to teach, and so here I am.’”

Baumgartner’s straightforward answer satisfied the students, who, she realized, didn’t want to “hear someone come in and talk to them about high-minded ideals.”

She notes that prison education programs reduce recidivism and create better employment opportunities for former inmates. “Whether you’re a prisoner or not, you have many more options in life if you have a college education. And if you are a prisoner and you have a felony conviction on your record, when you return to the outside, it’s very nice to have a college degree on your record too.”

Students also benefit in ways that are less tangible. “They gain a deeper understanding of the forces that shape communities, that shape themselves, that shape their children,” she says. “They learn that they have the power to act in positive ways in their communities that perhaps they didn’t feel they had before.

“And then there’s that ripple effect,” she adds. “They’re concerned with their children going to college. Now it matters to them.”

Regarding costs, she says “the college program is not as expensive as keeping people imprisoned.”

Approximately 150 women—or roughly 25% of Bedford Hills’ standing inmate population—are enrolled in the college program, Baumgartner says. And every spring, the program hosts a graduation ceremony. This year, she says, six women earned a bachelor’s degree and 14 received an associate’s degree.

‘A Fairer, More Effective Criminal Justice System’

Inmates at Bedford Hills have benefited from college education programs for decades. “Mercy College had a college program there until the tough-on-crime bill was passed,” Baumgartner says, referring to the Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act of 1994, which eliminated Pell Grants for inmates.

“Across the country, a lot of colleges, including Mercy, closed their prison programs in the mid-1990s because they just couldn’t afford it” without federal funding, Baumgartner says. The number of U.S. prison college programs dropped from about 300 to just a handful.

At Bedford Hills, a coalition of community members designed the college program, which is funded by private donors and grants. Since it began in spring 1997, more than 200 women have earned college degrees there.

And since 2016, it has also received support through the Department of Education’s Second Chance Pell Pilot program, a three-year experiment that aims to “create a fairer, more effective criminal justice system, reduce recidivism, and combat the impact of mass incarceration on communities.”

Inmates who take part in prison education programs are 43 percent less likely to return to prison in three years, compared to those who don’t take part, according to a federally funded RAND Corporation study from 2013, the education department noted in announcing the program.

Baumgartner credits the New York State Department of Corrections and Community Supervision for supporting higher education programs in prisons, including the one at Bedford Hills. “These programs sometimes tax their resources,” but the department understands their importance, she says.

Romagnoli talks with his Fordham students about his work at Bedford Hills, and about mass incarceration and criminal justice reform. “It resonates strongly with them,” he says. “And it’s something that’s really come into the public consciousness [in recent years]; the ball’s rolling a little quicker.”

‘Knowledge Is Power’

Back in the classroom at Bedford Hills, after a heavy but lively discussion about Ruined, Romagnoli gives the students a brief break before moving on to Zora Neale Hurston’s 1937 novel Their Eyes Were Watching God.

Asked to reflect on the course, which also includes discussion of philosophers from Socrates to Simone de Beauvoir, students say they’ve learned that “knowledge is power.” They say that “perception plays a big role in how people judge people,” that the readings have helped them “gain different perspectives,” and yet the class “brings a unity, even if we agree to disagree.”

“You learn more about yourself, about your ethical system, and you question the things you do,” says one student. “I am one class away from a B.A. When I leave here, I will always question the morality of a situation.”

—By Chris Gosier, Adam Kaufman, and Ryan Stellabotte