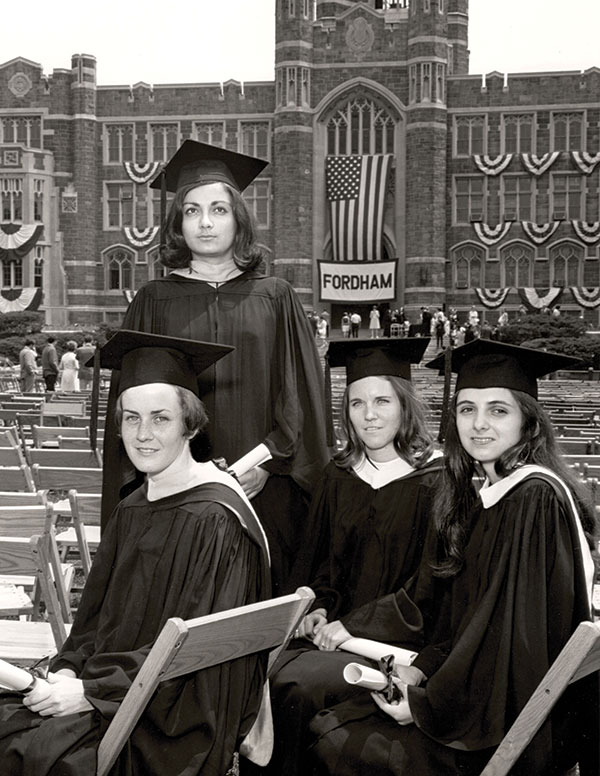

The photo shows four bright young women, diplomas in hand, ready to head their separate ways after making a little bit of history on June 8, 1968. They were part of the first graduating class of Thomas More College (TMC), the women’s college Fordham established four years earlier, and they would go on to become doctoral students, trailblazing professionals, wives, mothers, teachers, and mentors.

Mary Ellen Ross, Joanne Grossi, Cheryl Palmer Normile, and Susan Barrera Fay—a Fordham photographer brought them together on graduation day as representatives of their “pioneer class” of 210 graduates, the “first girls to invade the male environs of Rose Hill en masse,” as a University press release put it at the time.

They weren’t the first women to attend Fordham. Women had been earning Fordham degrees in law, education, social service, and other fields for nearly five decades. But they helped initiate a tremendous cultural shift at the University, one that culminated a decade later, when TMC graduated its last class and Fordham College at Rose Hill began accepting women. They challenged themselves and everyone around them—including skeptical faculty and students at the all-male Fordham College—to see beyond boundaries of expectations for women.

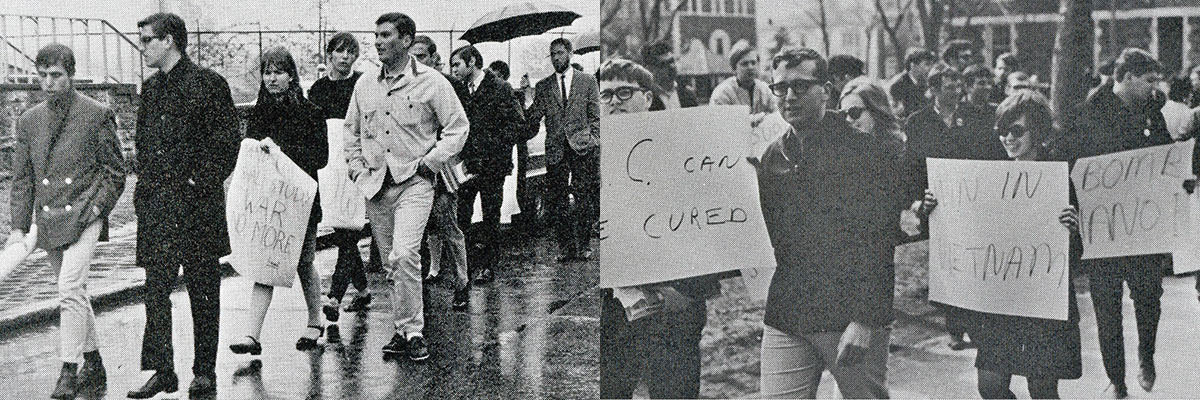

Their undergraduate days were also indelibly marked by social unrest—the civil rights and burgeoning women’s liberation movements, political assassinations, race riots, and anti-war protests that shocked and roiled the country.

“It really is hard to have perspective in the moment,” Normile said of being in the first class of TMC amid the “tumult” of the times. “But I think as women, we did have a sense that we were breaking some ground.”

Grossi expressed a similar sentiment. “When we got there,” she said, “we knew it was a big deal.”

‘She’s Done Well, She Deserves to Go’

Fay first visited Rose Hill for a debate workshop as a high school sophomore. “I thought it was a beautiful campus,” she said. So when she learned that Fordham was opening a college for women, she leapt at the opportunity. Admission was highly selective. In a letter welcoming the first incoming class to the University, Vincent T. O’Keefe, S.J., president of Fordham from 1963 to 1965, admitted, “[W]e don’t even know whether to call you freshmen or freshwomen.” But he praised their academic records: “Your College Board scores are collectively above average.”

Academic requirements were no problem for Fay, but finances were another issue. As the oldest of five children (the youngest was born while she was at Fordham), she wasn’t sure she would go to college at all. “My father said, ‘Maybe you should go to secretarial school, so when you get married and have children, you’ll have something to fall back on if you need it,’” Fay recalled. Not that he was unsupportive, she said, just worried about providing for the rest of the family. “And it was my mother, who had not gone to college, who put her foot down and said, ‘She’s done well, she deserves to go,’” Fay said.

Like Fay, Ross was already familiar with Fordham. She grew up on Perry Avenue in the Bronx, a 15-minute walk from campus, where her brother, Donald, was a senior and the student government president. “We were very different,” he said of his sister. “I was a glad-hander, and she was not, but she was very well organized.” Grossi remembers Ross as warm and well liked, and thinks her proximity to power, as it were, might also explain why she was elected TMC student government president. “There was a lot of, ‘Can you ask Don about it?’ or ‘Who do we see?’” Grossi recalled with a laugh. But the women were often on their own, and Ross felt the challenge of being first. “There was nobody to look up to,” she told the Fordham press office in her senior year. “We had to solve our own problems.”

‘They Were Not Ready for Us’

Most of the women were commuter students, as there were no campus residences for women until fall 1967. Grossi traveled from Jersey City, New Jersey; Normile from Mount Vernon, New York; and Fay from Queens. Ross walked to campus. Grossi’s and Normile’s parents eventually let them live in nearby apartments, both for the experience and, in Grossi’s case, because her science labs were early in the morning.

Some students lived in the Susan Devlin Residence, a Bronx boarding house for working women that was run by Catholic nuns and was so crowded, Grossi said, that some residents had to climb over other beds to get to their own.

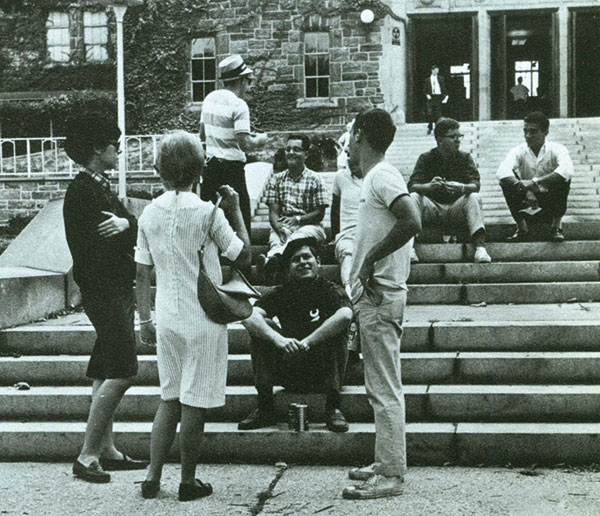

“They got us admitted and got us seats in classrooms, but they were not ready for us,” she said, recalling a dearth of ladies’ rooms and places for the women to gather on campus. Funny and outgoing, she succeeded Ross as TMC student government president. She said the administration tried to keep women in separate classes at first, but “in a year or two, we took classes with the men. And I think most of the guys changed their minds and got used to us.”

In a history class her first year, Fay was the only woman among about 50 students, she said. She found the last seat, in the back, where she hoped to go unnoticed. No such luck. Her future husband, John Fay, FCRH ’68, came in late and stood behind her, stealing glances at her name on her notebook. “The attempt to keep classes separate broke down quickly,” said Fay, whose facility with Spanish—her father was from Ecuador—landed her in advanced Spanish literature instead of an intro, girls-only section. “I hadn’t had boys in class since the third grade, so it was a bit of an adjustment.” She added with a laugh, “As soon as we got to higher-level classes, they weren’t going to have [separate sections of]Chaucer for boys and for girls.”

In a history class her first year, Fay was the only woman among about 50 students, she said. She found the last seat, in the back, where she hoped to go unnoticed. No such luck. Her future husband, John Fay, FCRH ’68, came in late and stood behind her, stealing glances at her name on her notebook. “The attempt to keep classes separate broke down quickly,” said Fay, whose facility with Spanish—her father was from Ecuador—landed her in advanced Spanish literature instead of an intro, girls-only section. “I hadn’t had boys in class since the third grade, so it was a bit of an adjustment.” She added with a laugh, “As soon as we got to higher-level classes, they weren’t going to have [separate sections of]Chaucer for boys and for girls.”

Normile attended an all-girls Catholic high school and never doubted that she would go to college. She remembers her guilt at skipping class with a friend one day to visit the New York Botanical Garden. “I did it, but it just bothered me,” Normile said of their little adventure, “because I knew the tuition was a lot for my parents.”

‘Beyond Your Own Little World’

The first class of TMC was graduating just as protests against the Vietnam War were dividing campuses, including Fordham’s, where military recruitment became an increasingly contentious issue. “People didn’t want recruiters on campus,” Grossi recalled. “It was a difficult time.” Fay’s boyfriend (later husband) joined the ROTC because he figured it was better to go into the Army as an officer than to be drafted. “It was a looming reality,” Fay said of the war. Her husband was not deployed to Vietnam, but many Fordham alumni were: 23 of them were killed, including four members of the Class of ’68, one of whom, Staff Sgt. Robert Murray, FCRH ’68, was posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor.

Normile recalled it as “a tense time, a disturbing time. But I think that kind of disturbance makes you think beyond your own little world,” she said, adding that a Jesuit education helped provide “a bigger balance” because it “encourages questioning, thinking, and exploring, and students were doing that on a much bigger level.”

Fay had an experience that took her out of her familiar world when she joined two mission trips to a sugar mill town in Mexico during the summers after her sophomore and junior years. She taught English classes there and lived in the parish rectory.

“It was an eye-opening experience for many of us, these privileged American kids going down to this little community where children had bloated stomachs and were walking around barefoot,” she said of the trips, which grew into the University’s Global Outreach program. “I think my attitude toward political and economic issues was shaped in part by seeing how people struggled to survive in Mexico,” she said, adding, “I also discovered I knew how to teach.”

Life After Thomas More

Fay and her husband were married in the University Church the year after graduation, and following moves to Hawaii, Chicago, North Carolina, and Texas, they eventually settled in Reston, Virginia, where they raised two children. She earned a doctorate in English from George Washington University and taught at Marymount University for 31 years before retiring in 2011.

Grossi majored in biology but also had a knack for computer programming. She worked in data processing at Con Edison and then at Chase Manhattan Bank, but both jobs proved unfulfilling, and the constant stress led to gastrointestinal troubles. The only thing that helped was visiting a chiropractor. “Even though people thought they were quacks, it worked for me,” said Grossi, who was so impressed she started chiropractic school herself in 1973 and became a practitioner. She retired on full disability in 1992 after being diagnosed with Lyme disease and lupus. “It’s very difficult, when you’re still in your early 40s, not to have a profession anymore,” Grossi said. “What do you do?” Volunteer work with the local YWCA is one thing that has kept her engaged.

Ross earned a Ph.D. in psychology at Syracuse University and was a professor of psychology and women’s studies for 30 years at St. Olaf College in Minnesota, where she found her niche.

Donald Ross remembers when he learned just how much of a difference his sister had made in the lives of her students. He was in Anchorage, Alaska, working on a juvenile justice project, and the administrator of a prison facility there had a St. Olaf mug on her desk. He asked her about it. She was an alumna, and she had known his sister. The woman began to cry when he told her that Mary Ellen had died, from Alzheimer’s, at age 66. “She said, ‘Your sister was so inspirational to all of the young women there, and treated us so well,’” he recalled.

Normile pursued a journalism career, which led to her becoming, she believes, the first female speechwriter on the staff of the secretary of the U.S. Department of Agriculture. Being a groundbreaking woman in the federal government in the 1970s meant facing sexist attitudes, despite holding a master’s degree from American University, Normile said. She left the USDA in 1981, got married, and later spent two years working on the Democratic Study Group of the U.S. House of Representatives before taking time off to raise two daughters and care for her parents. She returned to the USDA as a speechwriter in 1992, retiring in 2015. Her husband, Michael, died that same year.

Looking back, she attributes her decision to become a writer in part to William Grimaldi, S.J., a Fordham classics professor who encouraged her to go to grad school. “It was because of him that I came to D.C.,” she said.

Fay was also friends with Father Grimaldi—he presided at her wedding and baptized her children. Years later, when he was visiting the Fays at their home, they fell into conversation about the impact of women at Fordham. They reminisced about those days when everyone was navigating unfamiliar waters, students and Jesuits alike.

“He had thought it was not a very good idea” at the time, Fay said, “but over the years, he realized it was the best thing that happened to Fordham.”

—Julie Bourbon is a writer and editor based in Washington, D.C.