Frederick Douglass and the Fourth of July

Frederick Douglass and the Fourth of July

by James Colaiaco, PhD, FCRH ’67 (Palgrave Macmillan)

The subject of James Colaiaco’s fourth book, initially published in 2006, is one of the most electrifying speeches in American history.

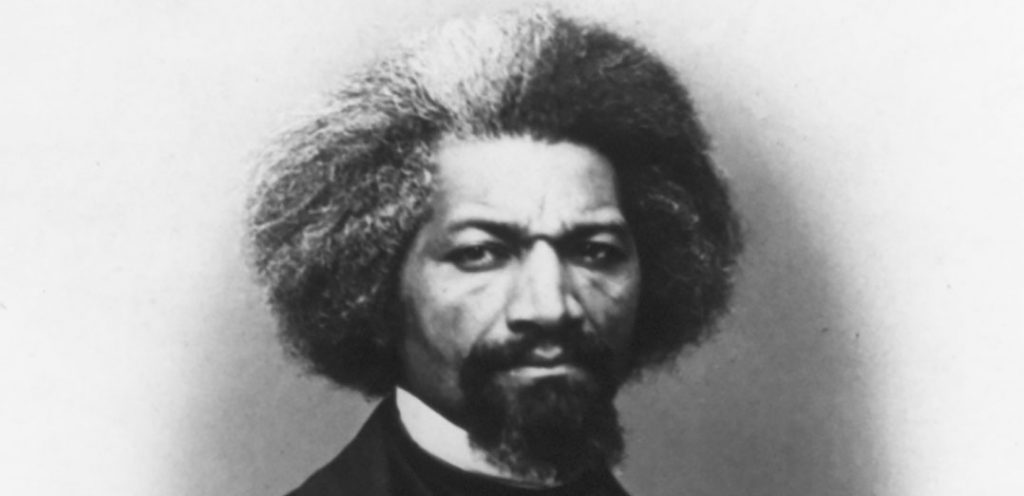

On July 5, 1852, former slave Frederick Douglass delivered a fiery, hopeful political sermon at Corinthian Hall in Rochester, New York, taking his fellow Americans to task for falling short of the ideals embodied in the Declaration of Independence—that “all men are created equal, that they are endowed with certain unalienable rights.”

For Douglass, Independence Day was a painful reminder of national hypocrisy, of the evil of slavery and of promise unfulfilled.

Colaiaco sets the political and cultural context while offering a close reading of Douglass’ speech, noting how he used a series of rhetorical questions to underscore the contradictions between the nation’s “ideals and [its] practice with regard to human rights.”

“Fellow-citizens, pardon me, allow me to ask, why am I called upon to speak here today? What have I, or those I represent, to do with your national independence? Are the great principles of political freedom and of natural justice, embodied in the Declaration of Independence, extended to us?” Douglass asked.

“Would to God, both for your sake and ours, that an affirmative answer could be truthfully returned to these questions!” To the slave, he said, “your celebration is a sham.”

Douglass skillfully invoked the Bible and the Declaration of Independence to strengthen the abolitionist cause, Colaiaco writes. And his speech took the shape of a uniquely American form: the jeremiad, a “political sermon” that begins with a reference to the nation’s promise—the Puritans’ “city on a hill”—before denouncing the people for falling short of that promise and concluding with a tough-minded but hopeful call for reform.

“Douglass shocked his audience,” Colaiaco writes. “Instead of congratulating them for having invited a black man to sing the praises of the republic, he had them, along with millions of white Americans, bowing their heads in shame for tolerating slavery.”

The scope of Colaiaco’s book extends beyond Douglass’ 1852 speech. He also considers the infamous 1857 U.S. Supreme Court Dred Scott decision, which affirmed the constitutionality of slavery and hastened the nation’s drift toward civil war. And in an epilogue, he assesses a speech Douglass delivered on July 4, 1862, in Himrods Corners, New York.

Douglass struck a more conciliatory tone in that 1862 speech than he did a decade earlier, but he still emphasized what Colaiaco calls the “American dilemma, the contradiction between promise and fulfillment.” And he appealed to President Lincoln to end slavery once and for all.

Six months later, on January 1, 1863, Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation, which “sounded the death knell of slavery in the South.”

Throughout his life, even after slavery was abolished, Douglass viewed the Fourth of July not as “a day of complacent self-congratulation,” Colaiaco writes, “but a day in which all Americans reflect on how far they have come in realizing the noble ideals of the nation’s Founders.”