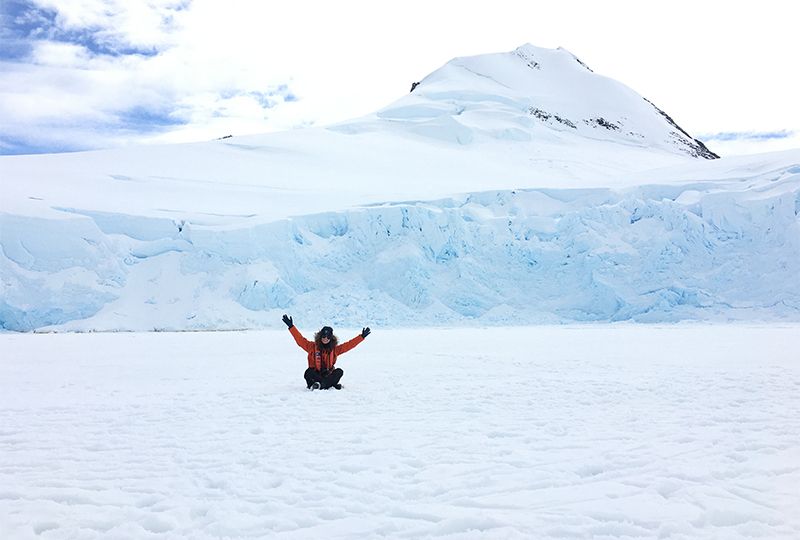

“Antarctica was just completely covered in snow and ice,” Flynn says. “I didn’t really think about [it]before going, but of course the sun is going to be reflecting off of all of this.”

The blindingly bright glare of the sun was just one of the remarkable things Flynn recalled about her three-week journey to Antarctica, the Falkland Islands, and South Georgia as a Lindblad Expeditions and National Geographic Grosvenor Teacher Fellow.

The fellowship, awarded to pre-K–12 educators who have shown a commitment to geographic education, sends recipients across the globe on Lindblad Expedition ships in order gain field experiences that they can bring back to their classrooms and institutions.

Flynn, who earned a master’s degree in biological sciences at Fordham’s Graduate School of Arts and Sciences, is the STEM initiatives program director for the Long Island Children’s Museum, where she has worked since 2016. In her role, she teaches informal education programs for elementary and middle schoolers, mentors teenage volunteers in creating sustainability and nature programming, leads an after-school program for high school girls to encourage an interest in STEM fields, and runs citizen science programs, among other duties.

In the summer of 2018, after completing National Geographic’s educator certification training, she discovered that she was eligible to apply for numerous grant and professional development opportunities through the organization, including the Grosvenor Teacher Fellowship.

“I applied knowing that it was very competitive, and thinking that it was kind of like a practice run,” Flynn says. “I would apply for it and then I would get feedback and apply again.”

Instead, she got the news that she had been accepted for the 2019 fellowship cohort.

Embarking on a Fantastic Voyage

Along with the 44 other members of her cohort, Flynn provided her preferences for destinations and scheduling, and from there, she was assigned to the National Geographic Explorer and headed for some of the southernmost reaches of the Southern Ocean. To prepare for their voyages, Flynn and the rest of the 2019 fellows participated in a multiday, hands-on workshop at the National Geographic Society headquarters in Washington, D.C., where they learned skills like photography and video editing and gained tips on outreach planning and public speaking.

After flying from New York to Miami, from Miami to Santiago, Chile, and finally from Santiago to Stanley, Falkland Island, on November 10, Flynn and the rest of her shipmates began their journey at sea. She was joined on the ship by one other fellow—an environmental science teacher from Miami—as well as paying tour guests and a staff of naturalists from varied backgrounds, including marine biologists, historians, geologists, and a guest speaker, Andrew Clarke, a retired polar ecologist from the British Antarctic Survey who discussed the effects of climate change on the area.

In the Falkland Islands, which is above the Antarctic Convergence and therefore has a relatively mild climate, Flynn saw flora and fauna that looked more familiar to her, including cows and sheep that were right alongside penguins.

When the ship reached its next stop, South Georgia, Flynn and her fellow explorers were able to get even closer to the wildlife there.

“South Georgia is covered in the most incredible mountains that you’ll ever see,” Flynn says. “And the wildlife that we saw there was amazing, in terms of the different kinds of animals that we saw, but also in terms of their number and how close you got to them.

“For instance, [the]penguins don’t have any natural land-based predators, and so they’re intensely curious. So if you just sit down, they’ll come right up to you. They’ll peck at your jacket and things like that. So, the ability to get so close to animals and really observe them in their natural environment was amazing.”

From there, the travelers made their way to the final part of the tour, Antarctica. Aside from the intensity of the reflected sunlight, Flynn says she experienced a landscape—and a seascape—unlike anything she had seen before.

“The colors that you could see in the ice were unexpected,” she says. “The water looked almost tropical because of how clear and blue [it]was. As you’re standing on the bow of the ship and just kind of going through the water, you could hear all of the crackling of the ice, which was really cool.”

A Close Look at Climate Change’s Effects

Of course, the trip was also an opportunity to observe the troubling effects of global warming in these places. Because the ship makes a similar trip every year, Flynn says that staff members described a front-row view of the changes.

“The captain of the ship has been with that ship [about]15 years, and he said that he’s seen noticeable changes in the past 15 years—where they can go and when in the season they can go,” Flynn says, noting that South Georgia’s Neumayer Glacier is receding two meters every day, according to representatives from the South Georgia Heritage Trust who spoke to the ship’s passengers.

Flynn says that the increase in annual temperatures has also created worries about biosecurity on South Georgia, which has seen devastation to native species because of the increasing hospitability to invasive species that find their way onto the island, including rats and reindeer. Before leaving the ship and setting foot on the island, she and the other passengers had to clean off their clothes, bags, and shoes to ensure that not even a single foreign seed or blade of grass made it onto land.

“[We had to] use a screwdriver or a paperclip to take out every single little piece of dirt,” Flynn says, adding that inspectors would check everyone before allowing them to exit the ship and would turn them around if they hadn’t cleaned off well enough.

That kind of experience is something that Flynn knew would be important to share with the students she works with at the Long Island Children’s Museum.

“My feeling going into this expedition was to ask as many questions as I could and try to figure out ways to talk to kids about climate change without it being ridden with anxiety. So as I’ve come home, I’ve been trying to figure out ways that I can disseminate information, but also have it be hopeful.”

Bringing Exploration’s Lessons Home

The sharing of information with students is an essential component of the Grosvenor Teacher Fellowship. The National Geographic Society requires fellows to provide regular reports during their two-year commitment as program ambassadors, during which time they’re expected to develop a student-action project inspired by the expedition, share the project plan as a resource for other educators, and organize a public event that connects their experiences to the larger community or their professional network.

Flynn is planning an exhibition, titled “Slow Down! Explore … A Journey to the Falkland Islands, South Georgia and Antarctica,” that is scheduled to be on display at the museum from April to June.

“In regular life, it’s very hard to find time to just kind of be,” she explains. “And I felt like on this expedition, I wasn’t the one who is responsible for planning anything. I could just watch the albatross, and I could just look at the elephant seals fighting. You notice a lot more. I felt like I wanted that to be a big component of this exhibit, because I feel like kids don’t have the luxury really of doing that.

“So, we’re going to focus on what it means to be an explorer and how to build curiosity, and the fact that you have to slow down a lot in order to observe or experience certain things. And that oftentimes travel is a way to expand your horizons and to discover new things.”

For Flynn, who had the opportunity to live in France for a year as a Fulbright scholar after her undergraduate studies at Adelphi University, her trip as a Grosvenor Teacher Fellow was filled with things to be discovered, experienced, and observed that were unlike anything else she’s encountered in her life’s travels.

One moment that stands out to her in particular involved an early wake-up that was worth every bit of sleep deprivation.

While in South Georgia, an expedition leader told the group they needed to get up at 3:30 a.m. to go to a place called Gold Harbour, where he promised they would see the most amazing sunrise of their lives. On the first day they went, there was so much fog that none of the colors of the sky were visible. The group was glad to get to observe wildlife at that moment in the morning, Flynn says, but there was some obvious disappointment.

Luckily, a few days later, the leader told them that the next morning, they’d have another chance to catch the Gold Harbour sunrise. This time, there was no fog, nor any disappointment.

“We went and it was the most incredible thing that I’ve ever seen,” Flynn says. “There [were]penguins walking across the beach, everything was bathed in this amazing light, and the sky changed colors from minute to minute. Everyone is so quiet and just kind of absorbing everything.

“You don’t really want to get up at three o’clock in the morning, but you think, ‘When am I going to be back here again?’”