In 2010, she co-designed and led Evoke, a future-simulation game for the World Bank that was pitched as a 10-week “crash course in saving the world.” It attracted more than 19,000 players in 150-plus countries. She asked them to envision the year 2020 and consider what they’d do to help themselves and others amid compounding crises—raging wildfires, the collapse of a power grid due to severe weather and aging infrastructure, the rise of a group called Citizen X that spread disinformation and conspiracy theories online, and a global respiratory pandemic.

In early 2020, as these story lines were playing out in all-too-real life, McGonigal began hearing from people who had participated in her simulations. “I’m not freaking out,” one person wrote to her at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. “I already worked through the panic and anxiety when we imagined it 10 years ago.”

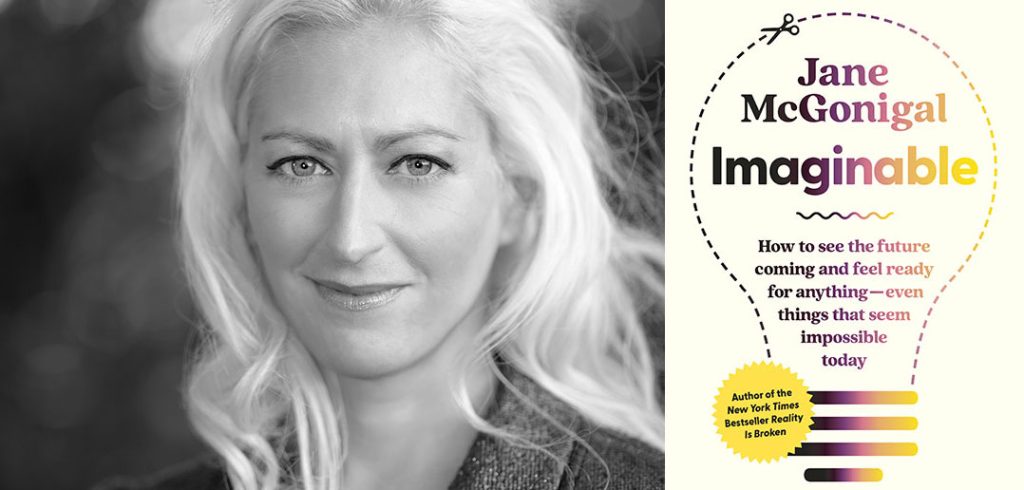

In her latest book, Imaginable (Spiegel and Grau, 2022), McGonigal lays out the tools people can use to “unstick” our minds and consider the “unthinkable,” balance our hopes and fears about the future; practice “hard empathy” to see the world from someone else’s point of view, and envision ourselves in various scenarios—some harrowing, some hopeful—in 2033.

The kind of “mental time travel” she espouses is not meant to be abstract. If it’s going to rain, it’s about “vividly imagining yourself in the rain, trying to pre-feel the rain on your skin.”

“The more vividly we imagine the worst-case scenario,” she writes, “the more motivated we feel to try to prevent it.”

McGonigal’s approach calls to mind St. Ignatius, the 16th-century founder of the Jesuits, who encouraged his companions to practice imaginative prayer—to put themselves in the Gospel stories, activating all their senses, as a means of feeling God’s presence in their lives and making choices about the future.

“A social simulation,” she writes, “is a springboard to making a better world.”

It’s a message McGonigal has been sharing for years, ever since she earned a B.A. in English from Fordham College at Lincoln Center in 1999 and a Ph.D. in performance studies from the University of California, Berkeley in 2006. Citing research in cognitive and behavioral science, and drawing on her own experience as a game designer and futurist, in several books, including Reality Is Broken (Penguin, 2011), she has made a compelling case that games can be a platform for people to improve their lives and solve real-world problems.

For McGonigal, prognostication isn’t the point of imagining the future; it’s about stretching “our collective imagination, so we are more flexible, adaptable, agile, and resilient when the ‘unthinkable’ happens.” And it’s about developing a sense of “urgent optimism”—an ability to think “creatively and confidently right now about the things you could make, the solutions you could invent, the communities you could help.”

It’s an approach that Andrew Dana Hudson, FCLC ’09, shares. In his debut novel, Our Shared Storm (Fordham University Press, 2022), he imagines five possible climate futures for the world based on decisions we make between now and 2054, when the novel is set.

McGonigal’s message also calls to mind something Fordham’s new president, Tania Tetlow, has said about a Fordham Jesuit education being right for this moment, “when young people are passionate about wanting to question assumptions and fix systems.”

In 2009, a decade after graduating from Fordham, McGonigal told Fordham Magazine that “the Jesuit idea of being in service has stayed with me. I see the games I create as helping to create a better community.”

It’s an inspiring message—and her optimism is not just urgent, it’s necessary, generous, and contagious.