Three years ago, McGill self-published the book Dear Marcus, inventing a name for his assailant, who was never identified. He never thought “Marcus” would read his words. Instead, he hoped others would find inspiration in his story—“people who question why bad things happen, and how you can get through a really dark period.”

McGill, who has full use of his upper body, also admits to dreaming of fame. “I was hoping through some crazy stroke of luck,” he said with a laugh, “I could get it to Oprah.”

The media mogul never called, but The New York Review of Books did, and acclaimed author Lorrie Moore reviewed Dear Marcus, calling it “short, sweet, homespun, and inspiring.”

“It was one of those moments where you’re in the shower and you actually have to catch your breath,” McGill said of hearing the news.

An editor at Random House, having read Moore’s review, tracked McGill down in Portland, Oregon, where he works as a college success coach, and offered to help bring his memoir to a wider audience.

In the book, republished by Random House in May, McGill describes with great care the unflinching support he received from his doctors, nurses, and physical therapists after he was shot—despite his sometimes cocky, rebellious attitude. “It wasn’t until later that I realized that that was unconditional love,” McGill said.

At 16, he became the youngest member of the National Theatre Workshop of the Handicapped, a group founded by a Jesuit priest, Rick Curry, S.J., who later helped McGill get into Fordham, where he earned a B.A. in English and made “a ton of friends.” After college, McGill traveled the world setting up international tours for disabled young adults. He also made a short film, earned an M.F.A. from Pacific University in Oregon, and taught high school for two years in Portland, where his curious students discovered his book.

McGill held an auditorium Q-and-A session about his experience, one he replicated at John Jay College in New York. He hopes to talk to more student groups, he said, and get Dear Marcus on some high school reading lists.

“The main thing I try to drive home is finding your inner strength,” he said. “That’s what’s going to pull you through in life.”

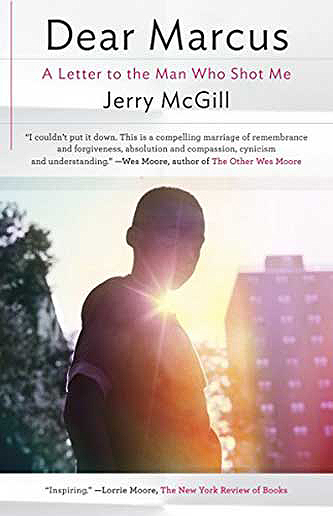

Book Review: Dear Marcus: A Letter to the Man Who Shot Me

Book Review: Dear Marcus: A Letter to the Man Who Shot Me

In this powerfully moving memoir, Jerry McGill explores the physical and emotional toll that a single act of violence exacted on his life—and the hard-earned lessons it taught him about accepting loss, finding inner strength, and learning the value of unconditional love.

On New Year’s Day, 1982, McGill was 13 years old, a smart, athletic, outgoing kid living in the Lilian Wald Houses on Manhattan’s Lower East Side. Life in the projects wasn’t easy for McGill, his younger sister, and their single-parent mother, but it was at least halfway hopeful. Despite living in a neighborhood and a housing complex marked by violence, cockroaches, graffiti, and the “usual scent of dread and poverty,” McGill writes, “a whole host of aspirations were floating around in that young imagination of mine.” He was getting more involved with the drama and theater program at Intermediate School 70, and hoping to attend the High School of Performing Arts, better known as the school featured in the 1980 film Fame.

But those adolescent hopes were snuffed in an instant. Walking home with a friend late at night on that first day of 1982, McGill was shot in the back just a block from his home. The shooter was never found, and the incident—unprovoked and senseless—left him paralyzed.

In recounting his experiences, McGill addresses his unknown assailant, giving him a name and several plausible circumstances that might have led him to pull the trigger that fateful evening. But, he notes, “I didn’t write this book for you, Marcus. My reasons for writing this are bigger than you or me, my friend. I wrote this book to release demons into the warm night air.”

McGill vents his justifiable anger—his frustrations with his condition, the opportunities lost, and the impact the shooting had on his relationships with his mother and sister. “My little sister should never have had to help me get dressed,” he writes. “You screwed up the balance in our relationship, Marcus. It should have been me taking care of her.”

But McGill doesn’t wallow in despair. “What-ifs can kill you if you let them, Marcus. They can eat you up like bone cancer or a flesh-eating bacteria.” And he relays his insights with no small degree of humor and compassion.

The heart of the book is McGill’s account of the six months he spent in the now-shuttered St. Vincent’s Hospital, where he struggled to regain some upper-body strength and relearn how to brush his teeth and feed himself, among other basic tasks. He writes with unflinching, unsentimental honesty about the people and events at “St. Vinny’s” that “helped to break me down and pull me up,” including the occupational therapist who cried with him when he learned that he would not walk again.

“I wonder, Marcus, if you’ve ever known a love like this,” McGill writes. “Have you ever had someone care about you so much that when you hurt, they hurt? When you need, they need? It is this kind of love that can make all of the difference in the world.”

McGill went on to attend a high school for disabled students. And he did not give up on his dreams, joining the National Theatre Workshop of the Handicapped, which was founded by Rick Curry, S.J., who later encouraged McGill to attend Fordham, where he earned a degree in English in 1992. McGill writes briefly about his postgraduate trials and successes, including his work as a group leader with a company “dedicated to taking young people with disabilities on international exchanges,” an aspiring screenwriter and filmmaker, and an advocate for the disabled.

And he ultimately comes to terms with Marcus. “I hope that you have felt guilt and shame,” McGill writes, “but I also hope that you have learned to let go of it all and forgive yourself. I honestly believe that I have.”

—Ryan Stellabotte