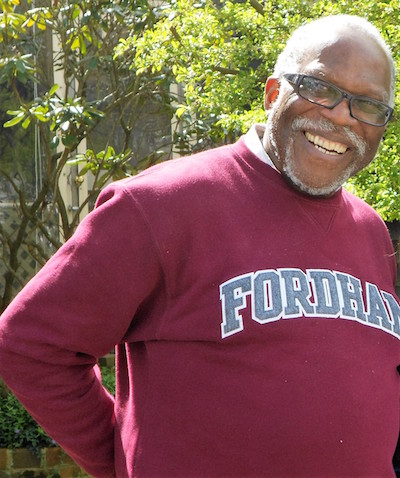

As a school administrator for nearly four decades, Peter E. Carter, FCRH ’65, faced some turbulent times and challenging situations: court-ordered busing, school district takeovers, and seemingly impossible financial crises. When he reflects on the confidence he needed to be successful, he often recalls his Jesuit education at Fordham. “We did all the things that prepared you for leadership without even knowing it,” he says. When a supervisor once denied him a promotion early in his career, he swiftly moved on. “He didn’t know I went to a Jesuit college,” Carter says, “where the next step is the next step up!”

As a school administrator for nearly four decades, Peter E. Carter, FCRH ’65, faced some turbulent times and challenging situations: court-ordered busing, school district takeovers, and seemingly impossible financial crises. When he reflects on the confidence he needed to be successful, he often recalls his Jesuit education at Fordham. “We did all the things that prepared you for leadership without even knowing it,” he says. When a supervisor once denied him a promotion early in his career, he swiftly moved on. “He didn’t know I went to a Jesuit college,” Carter says, “where the next step is the next step up!”

Carter spoke with FORDHAM magazine about his time at WFUV, Fordham’s radio station; his experience as one of very few black men on campus during the early 1960s; his eventful career; and his ill-fated judgment call regarding four mop-topped blokes from Liverpool.

As a Brooklyn boy, how did you choose Fordham?

Fordham was chosen for me. I went to Regis High School in Manhattan, an all-boys Jesuit school. The principal insisted students apply for Catholic universities. I was accepted at Fordham and offered a full four-year scholarship. As a poor kid of a single mother from low-income housing projects in Brooklyn, I certainly had to take that offer. I wasn’t given room and board, so my mother said, “We’ll move to the Bronx!” So I was a day hop. I majored in classical languages—Latin and Greek.

And you ran for student government?

In freshman year I boldly ran for student council office. I was vice president of the freshman class. I had what we called “the Regis vote.” In sophomore year I was treasurer, and I was in charge of funding for the concert committee [which arranged to bring musical acts to campus.] Our concerts included the Kingston Trio, Ray Charles, and Peter, Paul and Mary—my favorite. Our class started that committee—or at least formalized it.

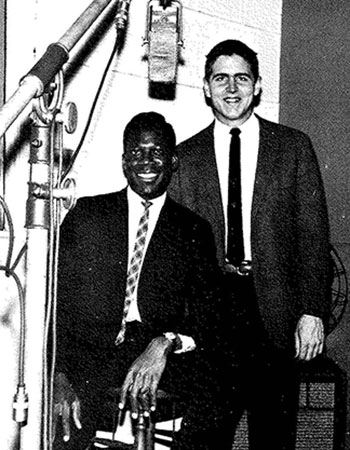

You became sports director at WFUV. What was it like in those days?

I joined WFUV in my sophomore year. There was an opening right away in sports, and I just slid into doing play-by-play for Fordham basketball and baseball. I later became sports director.

WFUV was on the third floor of Keating Hall at the time. There was a studio, a half office for the station manager, two turntables in the engineer’s booth, and a record library behind the booth. That was it. We were all student volunteers. It was comfortable. You could bring your books and study.

I did a segment called Around the Town about things to see and do in New York City. I covered the Beatles coming to Carnegie Hall in February 1964, [three days after their famous Ed Sullivan appearance]. I captured the excitement and the screaming young ladies.

Working with the concert committee, had you heard of the Beatles before they came to the U.S.?

In early 1963, the concert committee had gotten wind of this group from Liverpool called the Beatles. Someone said, “Let’s fly them in to the Fordham Gym and have them do a concert.” As the money guy, I was skeptical. I said, “What? The Beatles? What are they, some kind of insects? We’ll lose our shirts!” So I said no.

So when people say, what was the worst decision you ever made—that was the worst decision I ever made in my life. Fordham could have been the first place the Beatles ever appeared in the United States if not for Peter Carter.

As sports director at WFUV, you covered the return of Fordham football in 1964. What do you remember from that broadcast?

The highlight of our class, the Class of ’65, was that it was the one that brought football back to Fordham [as a club team]. This was a total student-run operation.

Our first home game was against NYU. We broadcasted it on FUV. We had to get a telephone line so we could hook it up to our tower at Keating Hall. Then I had to figure out how was I going to get on-field interviews. With microphone wire in hand, I crawled under the stands, which had been built by students, to have a microphone in place on the field. I did those interviews personally. Not everyone could buy a ticket, but people tuned in to 90.7 for a very live broadcast. And Fordham was victorious.

You were one of very few African-American students on campus at the time. What was that like for you and your classmates?

I was one of seven African-American students—or as they called us then, Negroes—out of 2,000 undergraduate students at Fordham College. I had to learn how to navigate around human beings who, through no fault of their own, had never met anyone like me. Their view of black people was from television. Or from watching black athletes. I chose not to be an athlete. I became a campus politician. It was an all-white campus, and I’m a campus politician. And the radio station sports director. [It was] a world that these guys kinda had to get used to. They liked and respected me. We all learned something about one another, which made us better off.

What was it like starting out as a teacher in New York City?

I wanted to give back to the Jesuits what they gave me, so I taught Latin and Greek for a few years at Brooklyn Prep [a Jesuit high school that closed in 1972]. Then the diocese opened an alternative school [for troubled students] called the New High School. I was maybe 26, and they asked me to be assistant principal. We did the best we could to help those kids grow, even though circumstances put them in a position where the world looked at them askance.

What were some of the greatest challenges of your career?

In 1975 I became principal of a middle school in New Castle, Delaware, that was educating 1,300 kids in a space with 986 capacity. I always remember that number—986. We turned that school around. The courts had just ordered the schools to be desegregated and we bused in black students from Wilmington. That was quite a challenge. They weren’t warmly received and they were scared. We worked very nicely—had a lot of social events and such—and soon they weren’t scared anymore.

Later, as Essex County superintendent of schools in New Jersey in 1989, I was responsible for 23 school districts, including Newark, which [the state] eventually took over because they weren’t able to get the job done. I helped lead that process. No one was happy and no one was pleasant. However, the important part is, we helped the kids.

The biggest challenge I had was in 1995, as superintendent of schools in Irvington, New Jersey. When I came, the district had a $9 million deficit. After four years, I left it with a $3 million surplus. I persuaded the entire staff, including myself, to take a one-year salary freeze. One time I had 24 hours to make a payment of half a million dollars to the insurance company or they were going to cut benefits to the entire staff. Using my persuasive skills—learned in part at Rose Hill—I got an advance in state aid and made the payment in time. That was the greatest challenge of my career and perhaps my greatest accomplishment. We can balance that out with the Beatles fiasco.

Interview conducted, edited, and condensed by Nicole LaRosa.