In Of Women and Salt, breakout novelist Gabriela Garcia takes readers from 19th-century Cuba to modern-day Miami, Texas, and Mexico, illuminating migrant mothers’ choices and the fractured legacies they pass on to their daughters.

As much as Gabriela Garcia loved creating stories when she was growing up, she didn’t plan to pursue fiction writing as a career. A Miami native, she studied sociology and communications, graduating from Fordham College at Rose Hill in 2007. She worked in the music and magazine industries and as a migrant justice organizer until she realized that writing fiction was all she wanted to do, all the time. She dove in, earning an M.F.A. from Purdue University, as well as several fellowships and awards that helped her turn her thesis project into a highly acclaimed debut novel.

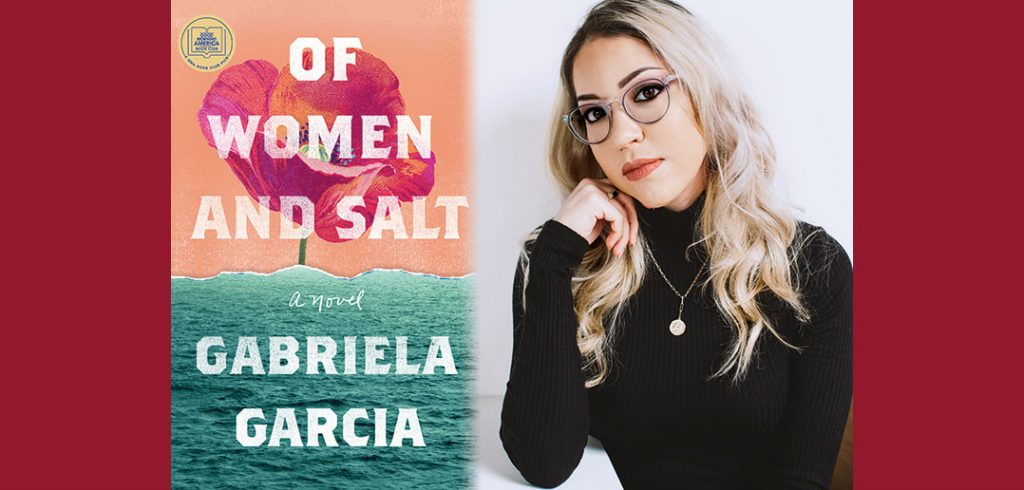

Published in April, Of Women and Salt (Flatiron, 2021) was immediately chosen as a Good Morning America Book Club pick and soon became a New York Times bestseller. In it, Garcia tells the intertwined, intergenerational stories of a group of women, starting in 1866 with María Isabel, a cigar factory worker amid the bloody stirrings of Cuban nationalists’ fight for independence from Spain, and ending with two of María Isabel’s descendants whose fates converge with those of a Salvadoran mother and daughter in present-day Miami. Jeanette, a first-generation Cuban American, is Carmen’s only daughter. She’s struggling to overcome an opioid addiction when she sees U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement agents arrest her neighbor Gloria. Despite a tenuous hold on her own life, Jeanette decides to take in Ana, Gloria’s young daughter. Of Women and Salt delves into the betrayals and the stories told and untold that shape these women’s lives and legacies.

Of Women and Salt combines your interest in Cuban history, American identity, immigration detention and deportation, addiction, and social privilege. What fueled those interests?

I’d been doing work around detention and deportation for many years, and organizing with a lot of women in detention. I grew up traveling to Cuba most of my life, so that’s something that I’m always thinking about. I was also really interested in writing against the idea of a monolithic Latinx community because I grew up in Miami, the daughter of a Cuban immigrant and a Mexican immigrant. Miami is a city that’s Latinx majority—one of the few in the U.S.—but there are all of these divisions along racial lines, along socioeconomic lines. I was interested in portraying the complicated version of Miami that I know. All of those things were swirling in my mind, and I wanted to find a way to be able to write into all of those interests.

Which character came to you first? Did you feel that you needed to tell readers more of any one character’s story?

Yeah. It’s been interesting to hear from readers how everyone gravitates toward a different character. Some people really wanted more from the María Isabel story, or wanted to see more of Gloria, or really connected with Jeanette, you know? It’s just been fascinating how people are super invested in different characters. When I started, I wasn’t sure who the hinge was going to be. As I was writing, it sort of became Jeanette.

Why did you choose this multigenerational, vignette format for the novel?

When I sit down for conversations with my family, we’ll start on one thread, and then it’ll go into something else, and then it’ll go into a memory and connect to other things. I wanted the book to have that feeling of stories, of memory, of historical accounting—where there are these spaces of knowing where it shifts kaleidoscopically.

While men hover at the periphery of the novel, male violence and abuse is a central theme. Talk a bit about your decision to have that experience or fear figure prominently.

I was really interested in exploring women navigating these really patriarchal worlds, in the generational echoes, and also in how women navigate male violence. I wanted to center the women and I wanted to write against a lot of tropes that exist, like even the idea of strong women surviving. I wanted to show that, oftentimes, there’s a cost for that survival, and that these expectations of strength are imposed when what a lot of these women deserve is rest or care or healing.

I was also interested in the idea of immigrant mothers as perpetually suffering or sacrificing as the expectation. Not that the women in my novel don’t often sacrifice or suffer, but they’re also so much more than that. There are times when Gloria questions if she even wants to be a mother. I wanted to show the relationship between women as they navigate these worlds.

There’s the expectation that it’s really noble that women should sacrifice everything as a mother, rather than asking why it’s necessary to have to sacrifice so much of yourself. What is there structurally or societally that requires that sacrifice?

A couple of 19th-century literary works figure prominently in your novel. How did you choose which books to feature?

I looked into the actual books that were read to workers in Cuban cigar factories during that time. That’s where the choice of Les Misérables and Cecilia Valdés came in. I sort of imagined this character of María Isabel as finding her world cracking open through literature, through these books that are read to her.

At the same time, I was struck by how most of the books being read to workers were overwhelmingly written by white, European men or white, European-descendant men in Cuba. I was thinking about how everything that she is absorbing is coming through this particular lens. That made me think about stories in general and whether there’s the ability to reclaim some of that story for herself, whether that’s even possible, and how things are passed down and how we absorb things—from what perspective.

I wanted to point to the ways that things can be inherited, but they don’t have an essential meaning. The books come to mean different things to different people throughout generations. Preserving just one meaning through generations feels almost impossible. I wanted to point to some of that impossibility, too, in the way that we pass down stories and histories.

—Interview conducted, edited, and condensed by Sierra McCleary-Harris.