Because, we’d say, he was a fulcrum in the lives of those who formed themselves around him. Because he paid us the compliment of driving us hard as students and then, in the decades to come, sustaining us individually and collectively with the shared bread of his friendship—like one of the righteous souls that the Talmud is always mysteriously crediting with holding this world together.

At least that’s how it seemed to those who knew him.

So we gathered on a cloudy day during the lingering pandemic in a stone church with its vault of azure blue. We warbled out upbeat songs, singing of alabaster cities gleaming, undimmed by human tears; of a tender Lord who extracts us when we’re snared like a bird in a fowler’s trap; and of the biggest promise ever made: resurrection after death.

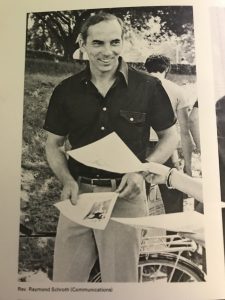

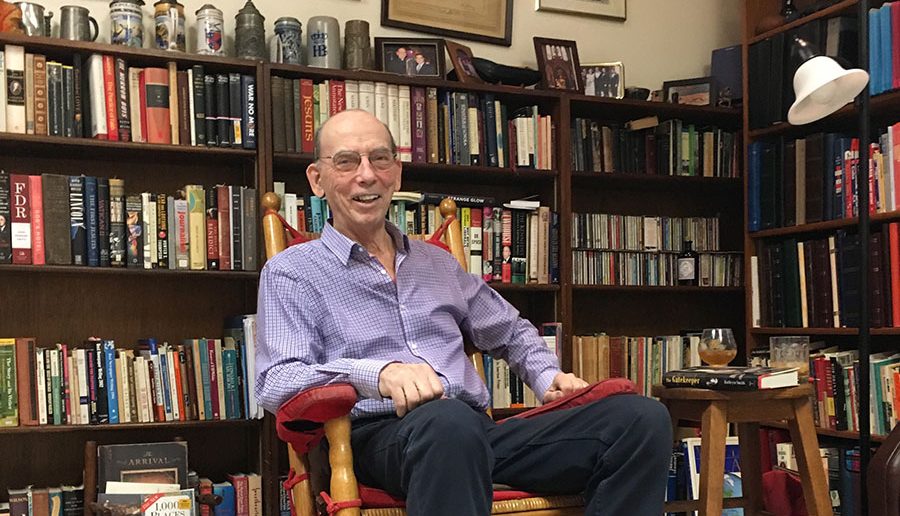

Most of us had begun as Ray’s students at one Jesuit university or another, Fordham included. He was blatantly magnetic, a man-about-campus with a playful smile and form-fitting Izod shirt. But his main devotions were interior: to intellectual pursuits and his vocation as a priest. He celebrated Mass with a marked sincerity and taught his classes with a passion. He published his writing—rigorous journalism with a disarming dash of memoir—in national publications. And in his music-filled apartment, next to the armchair, was an elbow-high stack of magazines and books. He would read them all, sometimes late into the night after a steak-and-martini dinner with friends at an Arthur Avenue restaurant, rebuilding the stack as he went.

Somehow, Ray made his life of the mind seem glamorous—like if you yourself couldn’t get in on it, you’d keel over from an acute lack of fulfillment. Then one day he’d tap you on the shoulder, so to speak, and allow that he saw something in you. This was both thrilling and nerve-racking for the way it made you want to measure up. It embarked you on what felt like an adventure of spiritual striving and cold ocean swimming, high literary endeavor and incessant bonhomie. The bonus was membership in a community not of his followers but his brethren.

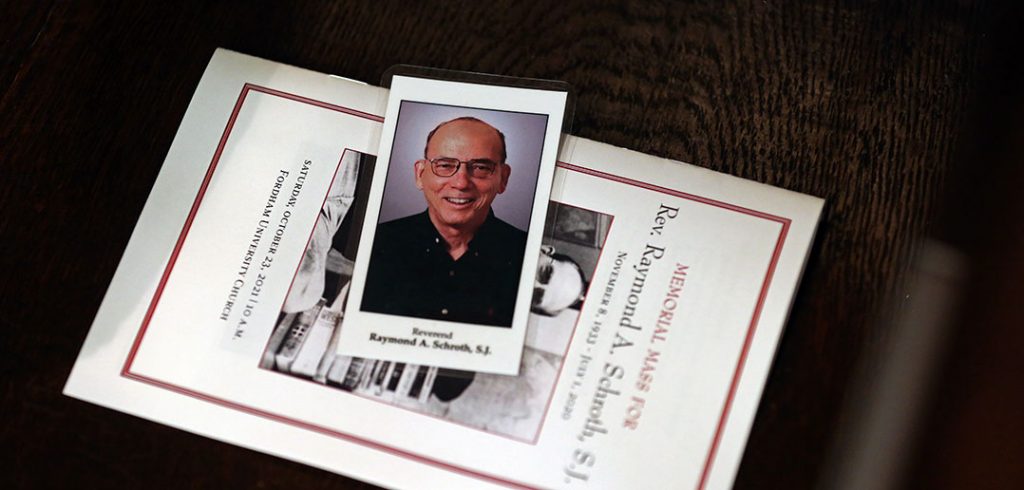

Years later, at the memorial at Fordham, a few of us sang his praises. “Ray was not a Catholic apologist but he was also not an apologetic Catholic,” said Kevin Doyle, FCRH ’78, a lawyer who has applied himself to defending men on death row. “He ached to be generative,” added Anne Gearity, TMC ’70, GSS ’74, about Ray’s zeal for teaching. She herself is a therapist who teaches children to cope with trauma.

Author Eileen Markey, FCRH ’98, noted the absence of Ray’s prize student, Jim Dwyer, FCRH ’79, who’d been one of his closest friends. A Pulitzer Prize-winning columnist of impeccably chiseled prose, Jim had been lined up long ago to deliver the eulogy. But before a memorial could be held, he died of cancer, a loss so devastating that it bordered on the absurd. All the more reason, Eileen observed, to gather at liturgy and find shelter with each other.

Afterward at a reception, there were mini muffins and comforting conversation, which is how I imagine the anteroom of heaven. Still, life haunts you. I kept dwelling on what Kevin Schroth, a professor at the Rutgers School of Public Health, had said at the Mass about the last two years of his uncle’s life: “Ray told me he was at peace with his condition, that he understood why he had to go through it.”

On a summer day in 2018, Ray was taking a walk on Webster Avenue when a stroke knocked him to the pavement. Remember those righteous men and women of the Talmud? This is how they quietly move among us, keeping chaos at bay through the practice of some discipline, until the chaos comes for them. Ray lost his ability to walk and write and gained a problem with swallowing that put him on a feeding tube. He entered a season of suffering. And yet, he clung to delight. He’d still beam at the sight of friends at his door, lifting his head as if lit from within. As if no loss in the world could keep him from loving you.

—Jim O’Grady, FCRH ’82, recently joined NPR’s Planet Money as a host and reporter after more than a decade at WNYC, where he earned numerous honors, including two Edward R. Murrow Awards. He is also the host of the podcast Blindspot: The Road to 9/11, a co-production of HISTORY and WNYC Studios.

Scenes from the memorial Mass and reception held at Fordham on October 23, 2021. Photos by Bruce Gilbert

[doptg id=”173″]