“I was told that my great-grandfather cobbled the shoes of the Jesuits there,” says Quinn, who earned a master’s degree in Irish history at Fordham in 1975.

Four years later, he left academia to become a speechwriter for New York governors—first for Hugh Carey until 1982, and then for Mario Cuomo. Quinn was a key contributor to several of Cuomo’s most memorable speeches, including his July 1984 keynote address at the Democratic National Convention—widely regarded as one of the most powerful of the past four decades.

Quinn left the governor’s office in 1985 to become the chief speechwriter for Time Warner—a transition he made while working on Banished Children of Eve: A Novel of Civil War New York, which won a 1995 American Book Award.

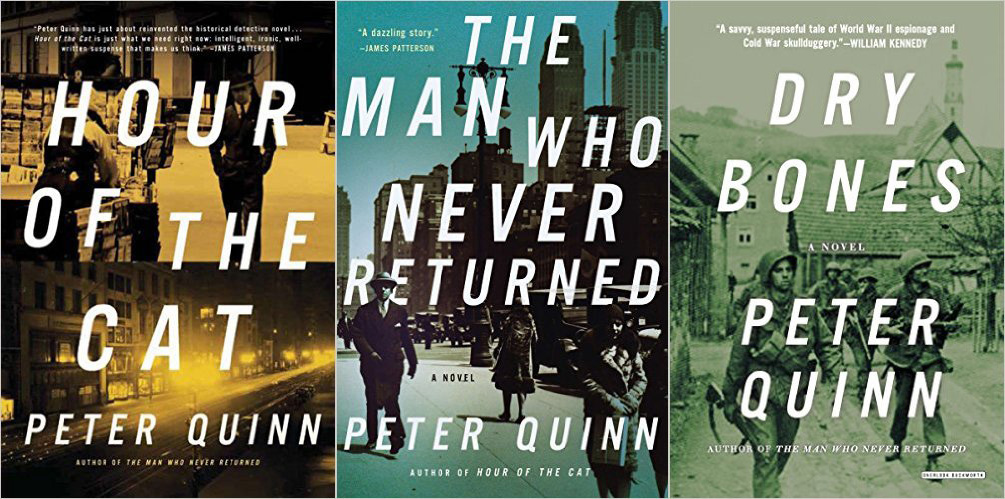

He followed that with a collection of essays, Looking for Jimmy: A Search for Irish America (2007), and a series of historical novels—Hour of the Cat (2005), The Man Who Never Returned (2010), and Dry Bones (2013)—all featuring private detective Fintan Dunne.

Quinn and his wife, Kathleen, have two adult children, both of whom are Fordham graduates. He recently met with FORDHAM magazine to discuss his family history, his writing, and more.

How much did you know about your ancestors when you were growing up? Did your parents talk much about them?

No. I mean, I heard anecdotes and I always knew I was Irish—our Catholicism was our Irishness. But I think my parents’ generation felt, “We’re moving into America. That is the past. There’s no need to have it beyond St. Patrick’s Day.” You’re very proud of being Irish, but the particulars of it were not of interest. I think in my parents’ case, and their parents’, they pushed their children ahead, you know, and made sure that they went to college. I only knew one grandparent, and they never talked about Ireland. Never. And I think they loved cities—you know, the whole Irish farming experience hadn’t been too great.

Your great-grandfather Michael Manning, how much do you know about what brought him to America?

It was the famine that would have brought him. He would have been one of the 2 million Irish who left in 10 years.

When did you really delve into that history and learn more about what the immigrant experience must’ve been like for him?

Well, that’s how I wound up writing a novel. I was studying for a Ph.D. in Irish history with Maurice O’Connell at Fordham. Then I left the academic world to go into politics, and I used to go to the state library to research speeches. I found this housing report for 1855 that was like a description of Dickensian London. I recognized that this is where my great-grandparents lived, and I had never heard anything about it. So then I began to look into that, the conditions in New York in the 1840s and ’50s. It had an infant mortality rate like the third world. It didn’t have a sewer system. So I realized, in a sense, why they didn’t tell us all this growing up. What was the use in knowing that?

Do you think there is a tendency to romanticize the immigrant experience generations later, and do you see a danger in that?

Oh, yeah, it’s a human tendency. It becomes part of a sentimental path rather than a reliving of the brutal reality that so many people go through.

And I think the danger is that you can lose sympathy with people in poverty and difficult circumstances now, thinking, “We were more noble the way we did it.” You forget the people who didn’t survive, who were victims of a lack of opportunity, poverty. We tidy it up. I always say America loves immigrants, but they have to be here two or three generations before anybody loves them.

People lose sight of the kind of labels and stereotypes that have been attached to new immigrant groups. The Irish, their disease was cholera. People thought they carried it with them. It came from tainted water, but people didn’t want to live around the Irish because they thought it was their disease, and they were judged to be mentally inferior to Anglo-Saxons. It’s like IQ tests, when they were first used at Ellis Island: They felt that Italians and Jews would bring down the national IQ. So you just see these things, and I don’t know how you cure it.

I think if you’re Irish and if you understand your history, if it doesn’t leave you with sympathy for the underdog, I don’t know what would.

You’ve written—both in Banished Children of Eve and in Looking for Jimmy—about the pivotal role Archbishop John Hughes, Fordham’s founder, played in galvanizing “the Irish-American process of reorganization” in the mid-19th century. How would you sum up his contributions?

I always say he was as much an Irish chieftain as a Catholic churchman. He’s the stem of the whole flower, the central figure, or however you want to describe it. He was here when a million Irish came out of Ireland from the famine, essentially skill-less, impoverished, and he was the mainspring of their reorganization. I always say that the Irish experience in America was about reorganizing. They were a mob when they came here. They had no financial resources. They had no education. They had no skills.

The engines of reorganization were the Catholic Church, the Democratic Party (which called itself the “Organization”), and the labor movement. The thing was to know the community was there, and it held together. Things cohered.

How did you go from grad school at Fordham to political speechwriting?

I wrote an article for America magazine in 1979 called “An American Irish St. Patrick’s Day.” I submitted it because, I didn’t know it at the time, but I was fascinated by this Irish-American experience that seemed to me to be going away without having been examined. We never looked at ourselves. Now we were moving to the suburbs. We were losing that thing I was talking about; the coherent thing was falling apart. But where was the record of it? Supposedly the Irish are great writers, but I couldn’t find any novels about the Irish-American experience. One, Elizabeth Cullinan, she wrote a beautiful novel, House of Gold, about the Bronx parish that I grew up in. But I remember everybody was horrified that she wrote it. She was putting out the family laundry. My mother was like, “How could she do that?”

So I wrote the article about this, and a Fordham alumnus read it and gave it to [New York Governor] Hugh Carey, who knew my father and was looking for a speechwriter. Out of the blue, they asked me to write the Fordham Law School commencement speech for him. I’d never written a speech. But I was looking for a job, and I didn’t want to be underemployed, so I wrote the speech. They really liked it and eventually offered me a job. I said I’ll do it for a year and then go back to academics. That was almost 40 years ago.

What did you learn from your experience in Albany?

To work in politics behind the scenes, you learn so much about the dynamics of human interrelationships, how much is based on personal relationships. Merit and hard work are no match for it. You know what was the great motto of the Albany machine? Honesty is no substitute for experience.

At what point did an academic career recede in your rearview mirror?

It receded when I got my second raise. I was making about twice what I’d been making. And then I got married. My wife is from the Bronx. We knew each other 14 years before we got married. That’s what’s known in the west of Ireland as a “whirlwind courtship.” She had moved to Albany for graduate school. She was a rehabilitation counselor. We reunited and got married. Finishing the doctorate would have been taking a big step backward. And some part of me always wanted to be a writer. It was an ambition.

Tell me about the genesis of Banished Children of Eve. I understand you initially thought you were going to write a history of the Irish in New York. Is that right?

I was an ex-academic. I still have a big interest in history. I used to send away for remaindered books. As I began to think about the experience of the famine Irish coming into New York, I realized there was really no central history written of it, this big event. I got one book on the Draft Riots, The Armies of the Streets [by Adrian Cook]. This historian did what no historian had done before. He went down and got the records from the morgue. They used to say a thousand people died in the riots. He could identify a hundred and something people. One of the names was Peter Quinn. My Quinn ancestors weren’t here yet. They didn’t come until 1870, but I was like, “Whoa, who is he?”

The personalization of history struck me. There were no diaries, no records. Nobody wrote. There’s not a scrap of paper in my family of anybody’s experience. So I wanted to write a history, but I began to realize the voices I wanted were not recorded. Then I found out that this songwriter, Stephen Foster, was in New York at the time of the Draft Riots. I went down—I think he committed suicide in the New England Hotel on the Bowery, and I stood in front of it. Every novelist is part psychotic; we hear voices. And standing there, I kind of felt I knew who he was. I had never written fiction, not a lick of it. But I said the only way I reach those voices is in novels.

How conscious were you of the fact that as a novelist you were drawing from your work experiences—for example, from the time you worked as a court officer in the Bronx?

How conscious were you of the fact that as a novelist you were drawing from your work experiences—for example, from the time you worked as a court officer in the Bronx?

At some points I was, absolutely. Dealing with a city, I felt like it was in extremis [as it was during the Civil War]. Being in the South Bronx in the ’70s in a uniform and sitting in a courtroom with 150 people and saying, “Well, you know, these people look poor and strange to me. And this is what my ancestors looked like to the people who were wearing the uniforms at that time.”

I figured it wasn’t just an Irish story I was telling at that point because once you stepped off those boats, you’re no longer Irish. You’re still Irish, but you’re becoming something else. And part of that experience is you have to interact with people you never had to interact with before. You might hate them. But you have to live with them, and some part of you is going to rub off on each other. That dynamic hasn’t changed.

Since 2005, you’ve published a trilogy of historical-mystery novels featuring the Irish-American detective Fintan Dunne. Do you see those books as part of a continuum that began with Banished Children of Eve?

Yes, Fintan Dunne is a descendant of Jimmy Dunne [in Banished Children of Eve], but I don’t know how. He’s a cousin somehow. The idea was that they would be three books that would stand alone, but in a way tell the history of New York from the First World War to the Cold War. And the thread would be this Irish-Catholic guy, Fintan Dunne.

I love Raymond Chandler. I always felt his character Philip Marlowe, he’s really Irish American with his hard-edged blend of cynicism and idealism, and he belongs in New York. So that was the inspiration for Fintan Dunne. I knew people that lived in that New York, and the thing about New York is, you never have to look for a story to tell. It’s right there in front of you.

How do you go about conducting research for your novels? When do you know enough’s enough?

I love doing research. Every writer wants excuses not to write, and research is the best excuse to have because you’re still working on the book. What I would try to do is immerse myself to the point where I would feel that I have some sense of that world. Then I would start to write, and if I had to look for other pieces, I would.

When I was researching Banished Children, my wife and daughter were away for the summer at Shelter Island. I would go out on weekends, but every night after work, I’d go to the newspaper division of the New York Public Library. I read all of the newspapers from the Civil War. I remember sitting there, and the air conditioner wasn’t working. It was August. I said, well, now I’ll read all of Harper’s Weekly. Then I realized I can either write this or research it for the rest of my life because the research is quicksand; it’s so interesting.

Did it get harder to stop researching for the Fintan Dunne books because it’s just so much easier to find things these days?

Oh, yeah, it’s unbelievable. I used to keep a list at my desk. I’d write down things to look up. Then at lunch hour—I was working at the Time-Life building—I’d run to the library. Now you just go online. It’s so much easier but not as much fun. It was so much more like detective work before. You were like Fintan Dunne. You were a gumshoe tracking stuff down.

What does it mean to you to be an American of Irish ancestry born in New York? What kind of cultural inheritance do those three things imply?

My father once said to me that the legacy of being Irish is having a sense of humor and rooting for the underdog. And if you’re going to live in New York City, those are two necessary things!

And I think the great thing about being Irish and Catholic in New York is you don’t have to be. Everybody can choose what they want to be. It’s not an identity imposed on you. Tomorrow, I could be an American Buddhist. To me, that makes it so much more valuable, you know, that freedom to be what you want to be that New York confers, I think, as much or more than any place in the world. I can be this. Then I can admit other people’s rights to their choices.

You’ve talked about storytelling as a noble occupation, something that unites us all. Would you elaborate on that?

You grow up, and you think there are serious jobs—accountant, lawyer, business CEO—and then you realize, the most important thing human beings have, the thing that makes us human, are stories. The first thing we did after we sat around campfires was to tell each other stories. It is essentially what it is to be human.

In every human society, one of the most important persons has been the storyteller, the seanachie in Irish. Before the Bible was written, it was spoken. Every religion is organized around a story. Every nation is organized around a story. Every family has its own myth.

Now I think there are bad stories. There are stories that are written or told badly, and then there are stories that are bad, like eugenics. That was a bad story. It was essentially a story that was used against other people to commit mass murder. Stories are very powerful.

One of the things I learned in writing speeches was that a good speech is a good story. And [Ronald] Reagan, one of his powers as president was, he had a story. He had the story of the frontiersman and the lone pioneer. One of the reasons why Cuomo is remembered is he had a story too—family, mom and pop. That’s what people listen to.

Do you ever itch to be back where you were—

To be young with hair? Sure, everybody does.

I mean, as a political speechwriter, having the opportunity to help tell a story in that way?

No. I’m really glad I did it. It was a defining experience. It helped me be a writer in ways I can’t describe. But I would never, ever want to do it again. For five minutes, I wouldn’t want to do it again. And I do think you have to be young to do it. It’s physically taxing. And it’s an exercise in anonymity.

Next month, you’ll be participating in a Fordham conference on “The Future of the Catholic Literary Imagination.” How would you define that term, and do you think of yourself as a Catholic writer?

When I’m writing, I never think about being Catholic. It’s just who I am. I’m not advancing any dogmas.

I have an essay in Looking for Jimmy where I said there are three elements to the Catholic imagination: sin, grace, and mercy. I wrote that years ago, and Pope Francis, the word he uses all the time now is mercy. We don’t want justice. We want justice for other people. We want mercy for ourselves. In politics, there’s not much mercy. It’s always been an in-demand commodity in the world, and it always will be, because it’s such a leap. Mercy is not deserved. It’s freely given, and there’s no rationale for it.

Interview conducted, edited, and condensed by Ryan Stellabotte.

Watch Peter Quinn’s New York, a five-minute video in which Quinn talks about his noir-tinged Fintan Dunne series and the city as muse. “For me,” he begins, “New York City isn’t so much a setting as it is a character. It destroys some people, elevates others. But one thing New York won’t do is leave you alone. It’s always changing.”