Among the most memorable dates in the baseball canon is September 9, 1965, when one of the greatest games ever pitched unfolded in Dodger Stadium. Sandy Koufax was on the mound, and the Cubs’ Bob Hedley was the only batter that stood between Koufax and a perfect game—his fourth career no-hitter. The winsome voice of the Dodgers floated over the airwaves to frame the moment in this poignant observation: “I would think that the mound at Dodger Stadium right now is the loneliest place in the world.”

In the end, the Dodgers walked away with the win, Koufax with his place in baseball’s Hall of Fame, and the commentator, Vin Scully, FCRH ’49, with the hearts of sports fans everywhere.

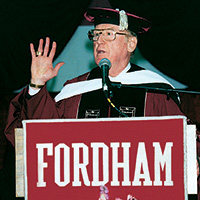

Scully hit a home run of his own in May, when he delivered the commencement address to the University’s Class of 2000. With the grace of a natural storyteller, Scully seamlessly blended anecdotes and advice, all in the honeyed voice that is so familiar.

“I am one of you,” he told the graduates. “I walked the halls you walked. I sat in the same classrooms. I took the same notes and sweated out the final exams; drank coffee in the café and played sports on your grassy fields.”

Scully said that the words he associates with Fordham are home, love, and hope. Fordham was home to him while he was a student at Fordham Prep and the University. He made lifelong friends there and loved every minute. And it was at Fordham that he began to pursue his hopes and dreams.

“Leave some pauses and some gaps in your life so that you can do something spontaneously rather than just being led by the arm,” he said. “And, above all, dream. Don’t ever stop dreaming. Dream for yourselves and dream for us because out of your dreams will come hope that we will have a better world and a better moral climate.”

Vincent Edward Scully’s story began in the Bronx, where he was born to a hardworking couple from County Cavan, Ireland. The Scullys sometimes walked young Vin in his baby carriage across Fordham’s Rose Hill campus.

“My mother once told me that she would say, ‘Vincent, I dream that someday you’ll study here,’” Scully has said. The dream was prophetic: In the 1940s, Vin won a partial scholarship to Fordham, where he majored in communications.

Outside the classroom, Scully wrote a sports column for The Ram student newspaper, was a stringer for The New York Times, and was a member of the Shaving Mugs, a campus barbershop quartet. He announced football, basketball, and baseball games on Fordham’s WFUV. A weak-hitting outfielder on Fordham’s baseball team, Scully managed to hit one home run during his college career. But the moment was marred somewhat when the Bronx Home News ran a photo of him in his moment of glory above a caption that identified him as “Jim Tully.”

Still, despite other interests, the young man had his heart set on broadcasting. Scully told the graduates that as a boy he would crawl beneath his family’s four-legged radio console during broadcasts of sporting events so that he could hear the roar of the crowd “wash over me.” Appropriate for the boy who would become the Voice of the Dodgers and, for many, of baseball itself: In the past 51 years, Scully has called Hank Aaron’s record-breaking 715th home run, three perfect games, 18 no-hitters, 25 World Series, and 12 All-Star games.

Scully graduated from Fordham in 1949 and spent that summer at a CBS radio affiliate in Washington, D.C. At 23, he returned to New York to talk to the network. Later that week, his mother came to him with wonderful news.

“She was flustered and excited,” Scully recalls. “‘You’ll never guess who called!’ she said. I said, ‘Who?’ She replied, ‘Red Skelton!’”

Actually, it was Red Barber, the network’s legendary chief sportscaster. Barber said CBS radio’s college football announcer was ill, and the station needed Scully to cover a game that Saturday between Boston University and the University of Maryland. Less than a year later, Scully landed a job on the Brooklyn Dodgers’ broadcasting team.

Scully also became a CBS and NBC announcer for baseball, football, and golf, and one of the most accomplished broadcasters in sports history. Inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame in 1982, he has won myriad sportscasting awards, hosted his own TV show, and played himself in films, commercials, and even on Sony PlayStation’s MLB 2000 baseball video game. Last season, he served as the emcee at Major League Baseball’s All-Century Team induction ceremony during the World Series.

But Scully admits that in 1950, he still had a lot to learn, despite being hired by the Dodgers for $5,000 a year. “Red taught me two important lessons that I still carry to this day: Trust your instincts and allow the crowd to help you tell the story,” Scully says.

Scully has long been known as much for his thoughtfulness, modesty, and gentlemanly demeanor as for his ability to paint word pictures for his audience.

New York Yankees broadcaster Michael Kay, FCRH ’82, says he was impressed with Scully’s graciousness when they met in the New York Mets press box. “He’s blazed a path for a lot of Fordham student broadcasters who are now in the business,” Kay says. In fact, Scully can be considered the dean of a Fordham tradition in sports broadcasting that includes Ed Randall, FCRH ’74; WPIX sports anchor Sal Marchiano, FCRH ’63; Mike Breen, FCRH ’83, the Voice of the Knicks; and Nets and Giants play-by-play announcer Bob Papa, GABELLI ’86.

Scully’s masterful delivery combines dugoutese and diamond pathos with a touch of poetry. He paraphrases Admiral Perry’s immortal words after a poor Dodger performance: “We have met the enemy, and he is us.” He describes bases loaded, no puts for the opposing team with the word, “The Dodgers have the sword of Damocles hanging over their heads.”

“He’s simply the best announcer in baseball history,” contends ESPN and San Francisco Giants announcer Jon Miller. “In high school, I once picked up a Dodger doubleheader on the radio while I was driving 10 straight hours to visit my grandmother in Oregon. Vin kept me interested the whole way. It’s more [than the fact that] he knows the game and does his homework; he has an innate sense of when and how to use information.”

Today, Scully, 72, says he believes that sports announcing was his destiny. The “Velvet Voice” has logged millions of miles traveling from ballpark to ballpark, and countless hours of broadcast time, but he has no plans to retire.

“I love what I’m doing, and I’ll continue to do it as long as I’m healthy,” he says. “I still get goosebumps when there’s a big play.”

—Bill Glovin