At a March 3 event co-sponsored by Fordham’s theatre program, panelists discussed the topic prior to the final mainstage season’s performance of The Luck of the Irish. The play explores how redlining affects two families: one Irish-American and one African-American.

Frank DiLella, FCLC ’06, NY1’s theatre reporter/producer, moderated the panel.

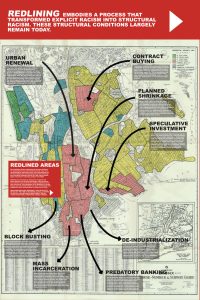

Gregory Jost, FCRH ’97, GSAS ’05, a partner at the social impact design firm Designing the WE, said that redlining differs from explicit racism in that it is a structural form of racism, and embedded into policy.

He said that when the federal government became involved in the housing market in the 1930s, it needed to evaluate risk. One way was to examine a neighborhood’s racial makeup and its “negro infiltration.” Neighborhoods with low “infiltration” were scored higher, and residents were more likely to gain access to insurance and loans. Along with valuable real estate came better schools and grocery stores.

“If you could create neighborhoods that were protected, it would rate highly and would increase property values,” said Jost.

Robin A. Lenhardt, professor of law and director of the Center on Race, Law & Justice, said that redlining should be viewed within the larger picture of racism.

“Racial inequality didn’t start in the 1930s; we can go back to slavery to study this subject and look at it in broader context,” she said. She noted that the play’s 50-year timeline allows an audience to grasp the intergenerational effects of systemic racism.

Jost said that some unsavory real estate speculators profited from redlining through “panic peddling,” where speculators bought homes in white neighborhoods and rented them to black families. The speculators would then offer to buy neighborhood homes from white home owners who were anxious to sell—even at a loss—lest their homes lose more value from “infiltration.”

Jost said much redlining happened during the Great Migration, when millions of African Americans moved from the South to Northern cities. Upon arrival they were offered unfavorable loans, while others who were once looked down on, such as Jews and Italians, saw their opportunities in society rise.

“You would only get a mortgage if you were white; this is how the Italians and the Jews became white,” he said.

In some areas that remained integrated in spite of redlining, he said, school systems became the de facto segregator.

“Kids played together until they were five and after that they went off to segregated schools,” he said, adding that when laws forced schools to integrate, neighborhoods saw “white flight” to the suburbs. While it’s now illegal to deny someone a loan based on race, a subtler form of bias has taken hold in the form of zoning, said Lenhardt. Some suburban towns use zoning laws to limit two-family homes, which are attractive to first time buyers.

“Using zoning laws to limit what kind of homes can be built . . . is having a [similar]effect of excluding people on the basis of race,” she said.

Jost showed video about Levittown, Pennsylvania as an example of white flight at the time of redlining.