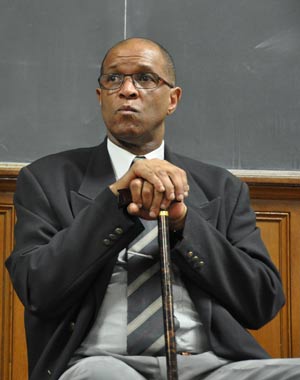

Photo by Janet Sassi

When Allen Jones was a kid growing up in the Bronx in the 1950s, the Patterson housing projects in the Mott Haven section were filled with promise—open, inviting doorways, the scent of home-cooking wafting from windows and grassy lawns edged with garden flowers.

But when the 1960s brought racial strife and urban decay to that same neighborhood, the 6-foot 6-inch teenager succumbed first to drugs and then to crime, throwing away his talent as a promising young basketball player.

On Oct. 3, Jones, co-author of the memoir The Rat That Got Away(Fordham University Press, 2009), shared the story of his dramatic downward spiral and eventual recovery with 75 Bronx high school students on the Rose Hill campus.

Speaking candidly to students in Fordham University’s STEP (Science and Technology Entry Program) and their parents, Jones recounted how he started sniffing “baby pounds” ($5 bags) of heroin one day after he’d been cut from the basketball team at Taft High School. The lure of the drug’s high, and the easy money he saw others making in the trade, led him to become a dealer.

Soon, Jones said, he was kicked out of Taft and became a street corner fixture outside of Morris High in the South Bronx—sporting a black Fedora, drinking Champale, sniffing himself high and dealing to his classmates.

“I had a briefcase full of heroin and we sold out in one hour,” he recalled. “We dealt inside the school, outside the school. People were coming up on us to buy drugs like we were the Red Cross. It was easy money. I thought I was bad.

“But the sad part was, I was selling death and everybody was buying.”

Sliding into debt in spite of his lucrative drug deals, Jones started robbing people at knifepoint to pay back his drug suppliers. He was caught and sent to Rikers Island for four months, unable to make bail. During a court appearance, however, a sympathetic judge opted for a lenient sentence after being moved by his mother’s pleas.

“After that break, I never looked back,” Jones said. “I took my same hustle, changed it over and got on the right track. I’m the same person, but my mind [has]changed.”

Jones got a second break when one of his mentors helped him pursue a college career in basketball. He went on to play at Roanoke College in Virginia.

Today, Jones works as a manager for foreign currency exchange at a bank in Luxembourg. Prior to his banking career, Jones played professional basketball and then did some coaching for Amicale Steinsel, a Luxembourg men’s team in the Eurobasket league. Jones’ son, Christopher, currently plays on the team.

“I shouldn’t be sitting here today, but the way I look at it is the Lord put me in all these different things in my life so I can help somebody else,” he continued. “And my message is, get a good education. Seize the moment. You’re in school, and you’ve got open minds. It’s up to you. Don’t blow it.”

Esther Brown, mother of George, a junior at Mount Saint Michael Academy, said she hoped the teens took Jones’ talk to heart. “He showed them they can handle themselves better,” said Brown, a native of the Bronx. “I never got caught up in that kind of life, and I tell my son every day to keep it moving and to keep out of trouble.”

Prior to the talk, Fordham’s STEP program director Michael Molina handed out Jones’ book to the students in attendance. After the presentation, Jones joined with the book’s co-author, Mark Naison, Ph.D., professor of African-American studies, for a signing.

Naison said that the book has been especially popular at Bronx schools such as Public School 140 and CUNY Prep, and at community youth programs. “One person after another has said that Allen’s story tells their story,” Naison said.

Molina said he invited Jones to speak to Bronx high schoolers because his was “a great Bronx story.”

“It’s a story of redemption,” Molina said. “It resonates.”