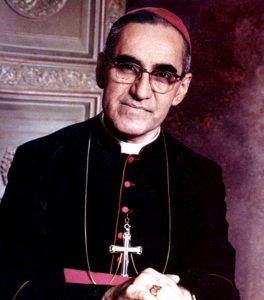

The day before Óscar Romero, archbishop of San Salvador, was assassinated, he delivered a sermon about the afflictions that besieged his home country of El Salvador during the late ‘70s.

At the time, hundreds of Salvadorans were being slaughtered each month by soldiers and right-wing paramilitary death squads.

“Let no one be offended because we use the divine words read at our Mass to shed light on the social, political, and economic situation of our people,” he said.

Though Archbishop Romero was accused by conservatives of using the Gospel to meddle into politics, Michael E. Lee, Ph.D., associate professor of theology, argues in a new book that he was modeling how faith can be lived out in an authentic way that changes the world for the better.

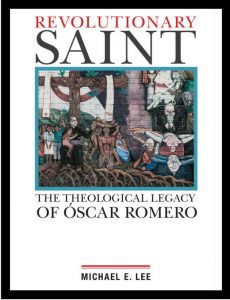

“His awareness of the reality of poverty in his country and the structural causes of it made him think about living his faith in new ways,” says Lee, author of Revolutionary Saint: The Theological Legacy of Óscar Romero (Orbis, 2018).

Not Partisan

The 1977 assassination of Romero’s close friend Rutilio Grande, S.J., a Jesuit priest in El Salvador, inspired his activism. He famously boycotted the presidential inauguration of General Carlos Humberto and other government ceremonies in protest of Father Grande’s death and the slaying of other community members who spoke out against repression.

The 1977 assassination of Romero’s close friend Rutilio Grande, S.J., a Jesuit priest in El Salvador, inspired his activism. He famously boycotted the presidential inauguration of General Carlos Humberto and other government ceremonies in protest of Father Grande’s death and the slaying of other community members who spoke out against repression.

“Romero always said faith had a political dimension—but it’s not partisan,” says Lee. “That’s an important clarification. It’s not about making one’s faith the same as one’s political party. Romero is talking about letting your faith and its conviction motivate you to transform society.”

Shortly after penning a letter to former U.S. president Jimmy Carter in 1980 asking him to reexamine U.S. support of the ruling Junta government, Romero was murdered while celebrating Mass.

“He was killed by people who ostensibly called themselves Christians,” says Lee. “Romero’s dynamic and engaged faith led to his death. Much like Martin Luther King Jr., Romero died in the struggle and out of a motivation of his own faith.”

Symbol of Conversion

In Revolutionary Saint, Lee contends that Romero’s death and journey to sainthood offers room for a larger discussion about themes like conversion, martyrdom, and liberation theology.

He notes that when Romero was appointed archbishop, he was initially a conservative priest who the Vatican believed would promote order and endorse the interests of the wealthy.

However, the kidnappings, torture, and massacres of coffee farm laborers in his rural diocese opened his eyes to the sufferings of the poor under the ruling elite.

“Romero was always charitable to those who were poor, but what marked him as an archbishop was that he stood for justice,” says Lee. “He called for changes in the structure of his country.”

Romero later established a legal aid for the Archdiocese of San Salvador to support victims.

“When the United Nations was investigating the human rights violations after the civil war in El Salvador, the office set up by Romero was one of the great sources of information,” says Lee.

‘A Church That Is Poor and for the Poor’

Thirty-eight years after his death, Romero is challenging the notion of what it means to be Catholic in a conflict-ridden society, says Lee. The similarities between the archbishop and Pope Francis, who supported the slain priest’s beatification in 2015, are reflective of Romero’s legacy.

“Romero and Francis have both adopted a preferential option for the poor, and when you do that, your idea of what the church should look like and what it should do is profoundly shaped,” says Lee.

As the process of Romero’s canonization continues, Lee notes that it is about more than just this one man’s legacy. It is a negotiation about how Christianity should be lived and the legacy of liberation theology—which is still viewed with suspicion in some Catholic circles.

Still, Romero’s beatification encourages Catholics to consider the vision of the church that Pope Francis has.

“When he became pope, he famously said, ‘I want a church that is poor and for the poor.’ And that is the vision of the church that Romero embodied,” Lee says. “It’s a way of moving forward that is hopeful for the Catholic Church.”