By Jenny Hirsch

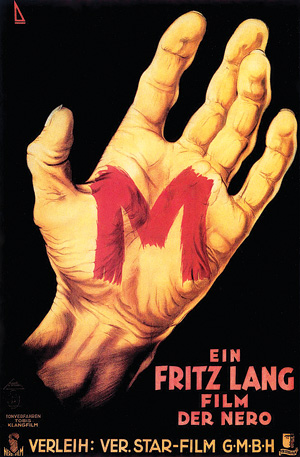

The 2011 Forum Film Festival concluded on Oct. 20 with a screening and panel discussion of M (1931), the first sound film by legendary director Fritz Lang.

The theme of the evening was how society should deal with the criminally insane—people like Hans Beckert, the film’s protagonist, who is remorseful about the child murders he commits but is compelled by his mental illness to carry them out.

The plot comes to a climax when the Berlin police begin cracking down on the underworld in an effort to apprehend Beckert, played by Peter Lorre. In response, the city’s criminals catch the child murderer themselves and subject him to a mock trial to determine his fate.

Beckert’s “defense lawyer” in the proceedings announces that the sick should be given to a doctor. At the timeM was produced, this was a new way of thinking and called into question how criminals were prosecuted.

“The defense was reasonable,” said panelist Sarah Williams Goldhagen, author and architecture critic. “What society needs to do with someone like that is isolate him so he can no longer murder—but not murder him because that’s antithetical to modernity.

“Peter Lorre is a character of modernity because he is someone who is described as having a psychological complexity and a pathology that happens with modernity,” Goldhagen said.

Panelists argued that the criminals have a window into the soul of Beckert because they are beholden to their own compulsions, such as the compulsion to steal.

They also learn about suffering. For example, a prostitute in the criminal court cries out to let the mothers of the murdered children decide Beckert’s fate. In doing so, the character suggests the concept of victims’ rights.

“This is the elevation of victims’ rights outside of the state’s interests,” said panelist Henry Bean, a screenwriter and director. “The woman criminal is saying, ‘You have to think of the victims’ rights.’ This seems to be the first time in film where this idea emerges.”

Panelists also discussed Lang’s use of architecture in M. Though most of the interior shots featured 19th-century architectural elements, the exterior shots showed modern Berlin as it looked in the 1920s and 1930s.

“Where they catch Beckert is the only modern building in the whole film,” Goldhagen said. “That suggests that if social institutions catch up to where modernity and technology are, then society will improve.”