Integrating Internationally at IPED

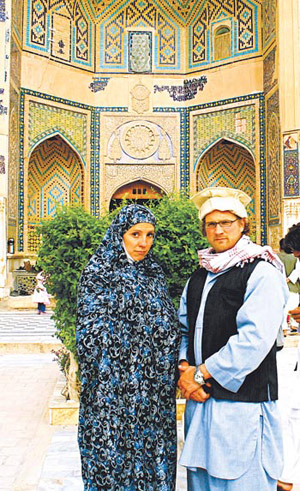

Two weeks after Joseph Kelly, GSAS ’04, won Fordham’s Swanstrom-Baerwald Award on March 6, he was sitting at the Philadelphia International Airport awaiting a plane that would take him to his new post as head of Syria’s Catholic Relief Services (CRS) offices.

Two weeks after Joseph Kelly, GSAS ’04, won Fordham’s Swanstrom-Baerwald Award on March 6, he was sitting at the Philadelphia International Airport awaiting a plane that would take him to his new post as head of Syria’s Catholic Relief Services (CRS) offices.

The award ceremony, recognizing a member of the Fordham community who excels in the service of faith, was but a memory, and his journey toward a war-torn, no-man’s land was 10 minutes away.

Kelly’s transnational story is not atypical for alumni from the International Political Economy and Development (IPED) program, housed in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences (GSAS).

“It’s going to be incredibly disorienting,” Kelly said by phone.

He wasn’t referring to his own journey, but to the scores of women and children refugees who would be arriving at CRS camps in Turkey, Lebanon, and Jordan about the same time he landed—most of them separated from male family members who stayed on in the Syrian cities to protect their homes.

“It’s a schism within the family unit,” said Kelly, who preferred to focus on the job at hand rather than his recent award. “Here you’ve got people who are stranded on borders, in limbo, and who will be waiting for an indeterminable amount of time.”

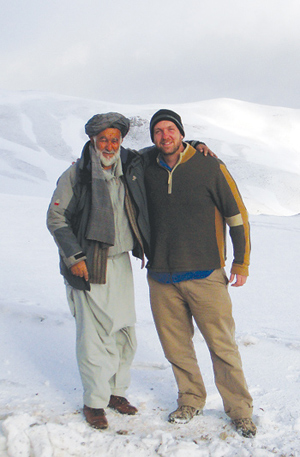

About 6,000 miles away in CRS’s Jerusalem office, Kelly’s old IPED classmate and good friend, Matthew McGarry, GSAS ’04, was settling into his new role as CRS’s country representative to Jerusalem, the West Bank, and Gaza. McGarry was Fordham’s 2011 Swanstrom-Baerwald Award winner. Via Skype he described his and Kelly’s “bizarrely parallel life paths.”

About 6,000 miles away in CRS’s Jerusalem office, Kelly’s old IPED classmate and good friend, Matthew McGarry, GSAS ’04, was settling into his new role as CRS’s country representative to Jerusalem, the West Bank, and Gaza. McGarry was Fordham’s 2011 Swanstrom-Baerwald Award winner. Via Skype he described his and Kelly’s “bizarrely parallel life paths.”

The two attended Notre Dame University as undergrads, but didn’t meet until they were working as Jesuit Corps volunteers in Latin America. It was there that they decided to apply for IPED’s Arrupe fellowship, which they both received.

At Fordham they became roommates and later went on to work for CRS in Afghanistan for two years. While Kelly’s and McGarry’s coinciding trajectory isn’t the norm, McGarry said that contacts formed during the IPED years helped shape his approach to his work.

“It’s a relatively small, tight-knit program, and the classes are quite diverse, not just in terms of interests but also in terms of geographic origin,” he said. “In addition to students coming from nonprofit groups, there were midcareer diplomats and people who were working on Wall Street as well.”

IPED’s diversity separates it from the average policy and/or business program. The program merges international politics, economics, and development. Not all of its graduates move on to nonprofit development like Kelly and McGarry. In fact, two-thirds of the students move into the government or private sectors, said Henry Schwalbenberg, Ph.D., IPED’s director.

“All IPED students share a common interest in international affairs and they all have a common interest in the economics of it,” said Schwalbenberg.

The experience of rubbing elbows with classmates who are about to, say, defuse land mines in Laos, does have an effect on the Wall Streeters, he said. A diverse group of students can also benefit one another in the real world, sharing information if the private sector may be hiring when the nonprofits and governments are cutting back, or vice versa.

For McGarry, training alongside government- and private-sector-bound students paid off.

“It encouraged a variety of perspectives, rather than thinking in lockstep with other likeminded NGO-bound students,” he said. “It also helped me understand people who go into government or into socially responsible corporate entities. As funding becomes more competitive, we rely on them. So it’s good to know who is manning the gates, not just some passing familiarity.”

That relationship goes both ways, said Joseph Quinlan, GSAS ’83, chief market strategist of U.S. Trust, Bank of America Private Wealth Management. Quinlan said that IPED’s multipronged approach to studying international economics and development benefits those heading into the financial sector as well.

“As a global money strategist, you want to bring all those disciplines together,” he said. “Since you have to do political risk analysis, all those variables matter. It helps to tackle macro problems on a global scale.”

Quinlan said that while the M.B.A. remains important, more and more companies want the multidisciplinary approach that IPED fosters.

“IPED doesn’t create generalists, it creates global problem solvers, from bottom up to top down,” he said.

Quinlan said he likes how the program has evolved since he went to school and how “it kept up with the times with more opportunities to travel.” He backed up his support by creating the IPED endowment in 2007. The endowment awards scholarships that provide support for international travel, research, and other expenses.

Quinlan is also part of another unique IPED pairing. His son, Brian Quinlan, GSAS ’09, is also an IPED graduate, though the younger Quinlan opted for roles in the nonprofit and government sectors—first with CRS and now with the Department of Homeland Security.

“Through an IPED education, you get so much from your peers,” he said. “I have classmates who are at Ernst & Young, classmates who went to Burma to work on procuring medicine for malaria, and classmates in the State Department shaping policy—the conversations with them were worth their price in gold.”

Before joining the Department of Homeland Security, the younger Quinlan was in Laos working with CRS in their ongoing effort to rid the country of land mines left behind from the Vietnam War.

“The work does deeply impact you on a personal level, to see how that war is still hurting people all these years later,” he said. “It hits home to see nine-year-old kids affected by these bombs [that explode decades later], when they don’t even know what the Vietnam War is.”

He said the experiences equipped him with skills for life.

“IPED is so multidisciplinary, it gives you a lot of tools. It gave me one set for Laos and a whole different set for my Homeland Security job.

“It’s always important to have a lot of tools in your tool box.”