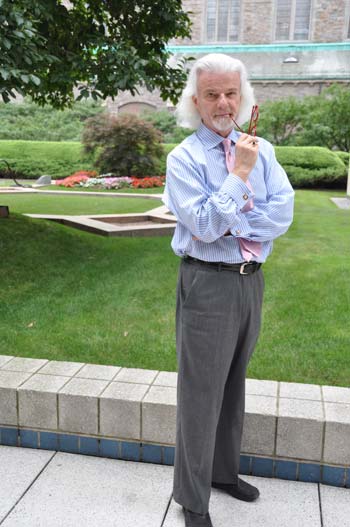

Photo by Nina Romeo

Most people associate stories and storytelling with childhood or literature, films or television. But how many of us are aware of how intricately the wider spectrum of our lives is enmeshed with all types of narrative forms?

For James VanOosting, Ph.D., professor and chair of communication and media studies, it is natural to see storytelling as inextricably linked to how we learn and transmit to others what we know.

According to VanOosting, “We are born into stories, predated by place, time, action, and other characters. We may think we start from scratch, but we don’t. Early on, we’re not the narrators of our own stories. We’re mere characters, and it takes a long time to wrest narrative control, if we ever do. Power is deeply implicated in who exercises the narrative rights to one’s life story.”

VanOosting’s careful listening has instilled in him a love of story that has led to the publication of four novels for young readers as well as a collection of personal essays titled And the Flesh Became Word: Reflections Theological and Aesthetic (Crossroad Publishing, 2005).

His personal interest in storytelling has informed his scholarly pursuits, which focus on the ways humans use narrative to acquire, store, access, disseminate, validate or invalidate what it is we think we know.

The connection between memory and stories is integral to this work. “We store our life experience in narrative,” VanOosting said. But the process and results of memory storage are far from straightforward.

Employing an interdisciplinary approach, VanOosting examines breakdowns and inconsistencies in memory. “Neuroscientists are finding it’s not so much that the brain forgets over time, but that the brain is so good at making up stories,” he said. “It appears that memory is predicated more on narrative intrigue than factual recall.”

Another feature of his work is the separation between narrative and narrator—or story and storyteller. “One story could be told so many different ways by different people,” VanOosting said.

This difference may be as benign as a disagreement between family members who have different versions of the same incident. But if people look to recent events, they could see how the telling of a story can, in fact, become a matter of life and death.

VanOosting pointed to incidents in the months before the war in Iraq as an example of how cultures use stories to validate or invalidate information. He recalled the key question on which future events were hinged: “Are there, or are there not, weapons of mass destruction?”

“I didn’t know,” he continued. “I couldn’t go over there with a spade and dig around. I had to listen to competing narratives and adjudicate their validity.”

As is now known, weapons of mass destruction did not exist, but VanOosting noted how the testimony before the United Nations Security Council of former secretary of state Colin Powell helped to sway opinion in support of military incursion. As a respected and trustworthy figure in the Bush administration, Powell was seen as a credible storyteller.

“Aristotle would say Powell didn’t persuade by logos or pathos, but by ethos. I granted authority to his reputation,” VanOosting said.

Reflecting on the deadly aftermath of the Iraq War debate, VanOosting said that “a lot rides on narrative validity, including personal power, interpersonal persuasion, and cultural authority.”

Listening to VanOosting speak about stories helps someone to get a sense of how pervasive narrative is across disciplines and professions. While it is easy to see how stories may operate in the fields of anthropology, sociology, history and theology, it may not be immediately apparent how stories are also implicit within propositional arguments or mathematical formulas.

“Einstein, for instance, said there were certain presuppositions that he began with and those were rooted in narrative, in certain beliefs that he had about cosmology,” VanOosting said.

A similarly surprising place to encounter story is in the field of medicine. VanOosting refers to Columbia University’s Department of Narrative Medicine. In that clinical program, health care professionals learn to elicit stories from patients and become “textual critics” to produce more accurate diagnoses and provide better treatment.

When VanOosting completes the novel he’s currently writing, he plans a book on narrative cognition to add to his list of six other non-fiction titles. Also, he has inaugurated a graduate-level course in communication and media studies titled “Narrative Thinking.”

“I’m interested in how new media technologies shift our relationship to narrative,” he said. “Take Twitter. We’re now narrating our lives, not unlike early childhood when we narrated our own actions in order to connect behavior with language. I’m intrigued by what fundamental changes may be entailed in this shift from dramatic to narrative discourse.”