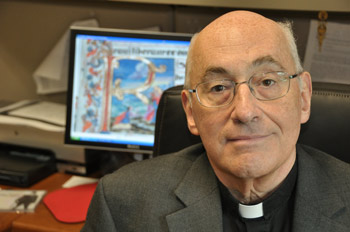

Photo by Janet Sassi

For years, what lay in a small convent in Kraków, Poland, behind the Iron Curtain remained a mystery.

James Boyce, O.Carm., Ph.D., associate professor of music and scholar in medieval Carmelite manuscripts, had heard rumors of an unstudied set of choir books existing in a small convent known as Na Piasku, or “on the sands”—named for its original 1397 location outside the city walls of Kraków.

To a scholar like Father Boyce, who wrote his doctoral dissertation on two sets of manuscripts, one from 14th-century Florence and the second from 15th-century Mainz, at the time the only known sets of Carmelite choir books, the notion of such undiscovered devotional objects within his own order was an exciting prospect. During the 1990s, he tracked the books’ existence through what he heard through other people’s visits and through a friend who took some pictures of the books. But the sources proved somewhat cursory and inconclusive.

When traveling restrictions eased on the former Eastern Bloc nations, Father Boyce began planning his visit to the convent. It happened in 2000.

“It was a voyage of discovery,” recalled Father Boyce. “I really had no clue what I would find. People had said the books were all 18th century. But when I saw the work, I gasped. These books—the earliest ones—were 600 years old. Now that’s old, even for our order. It was then I realized how valuable they were.”

Father Boyce documented his journey and the minute details of his discovery in Carmelite Liturgy and Spiritual Identity: The Choir Books of Kraków (Brepols, 2008). The 500-page book reveals the contents of some 25 choir books spanning 600 years, and offers an intimate look into the liturgies and daily rituals of the early Carmelites.

The book also places the choir books within the historical context of the Carmelite tradition, suggesting that they are “instruments of identity” for an order that was seeking to define itself, especially throughout the Middle Ages. The books would have been used several times daily to perform the Divine Office, a collection of prayers and Gregorian chants that occupied up to four hours of the friars’ daily activity.

Three of the books, Father Boyce said, most likely traveled with the Carmelites from Prague, Bohemia, in 1397, when they set up just outside the city walls of Kraków in a burgeoning immigrant neighborhood. Another book, a 1644 Gradual, or book of chants for the Mass, includes some 110 “historiated” initials in brilliant hues and intricate gold leaf. The books date up until the 19th century, with the earlier medieval manuscripts being of such rarity and beauty that Boyce describes them as devotional objects.

“Just one ordinary ‘D’ is so beautifully decorated with blue grillwork, and there’s a little picture inside the letter,” Boyce said. “It must have been on display for people to look at and venerate. It couldn’t have just been used by the people who sang from it.”

Making even one book was an intricate undertaking from start to finish. The area known as “on the sands” was teeming with recent immigrants who worked as tanners, butchers, parchment makers and other trades, so the materials were right on hand. It would take one entire sheepskin, strung up, de-wooled and planed down, to make two folios (four pages) of parchment.

Next, the book had to be ruled, and both text and music inscribed in ink by the friars. The more intricate historiated initials, Father Boyce said, most likely were done by professionals. “Everything had to be done very carefully. There was no correcto-type, no do overs,” he said.

The books are roughly the size of a suitcase: about 3 by 4 feet, containing 400-500 pages and weighing approximately 60 pounds. Inscribed in one book is a colophon, listing the names of all the friars who worked on its creation. “It’s very moving to read the names and realize the amount of work they put into the choir book,” Father Boyce said.

He said the choir books distinguish the Carmelites among Catholic orders for their liturgical uniqueness. As one of the earliest orders of the church (whose legend says they were formed in the Holy Land), Carmelites pay homage in liturgies to Elijah the Prophet as their founder.

But the Kraków books in particular also celebrate some little-known saints, such as St. Ludmila, a ninth-century martyr who struggled to convert Bohemia to Christianity.

“Until the discovery of these books, this office was totally unknown in the Carmelite tradition,” Father Boyce said. “But the Carmelites of Kraków never lost sight of the fact that their founders were from Prague (Bohemia).”

One of the original books was sold to pay for a painting project in the chapel, Father Boyce said. The other 25 books left the convent only once, in 1655. During a war with the Swedes, the friars buried the books in town before the monastery was burned. Once it was rebuilt, the manuscripts were returned.

They also survived the Nazi invasion in the 1940s, when half a dozen priests were sent to concentration camps—“simply because they were clergy,” he said.

“These books [have]survived the communists, too,” he said, “and they’ll be around long after you and me.”

The books, said Father Boyce, provide a strong sense of “who these Carmelites were” and how they operated in a new country among more established orders.

“When Pope Boniface IX accepted us into Kraków, he was interested in expanding religious life and observance,” he said. “Living on the outskirts, the Carmelites helped ensure the orthodoxy of the immigrants and enhance the spiritual tradition of the local church. They interacted well with the city.”

– Janet Sassi