Colin M. Cathcart AIA

Associate Professor of Architecture

Associate Director, Environmental Studies

Principal, Kiss + Cathcart, Architects

Can the Big Apple become the Green Apple? Can New York City, famous for greed, power and exploitation, maintain its position as the “Capital of Capital” while becoming environmentally sustainable?

Can the Big Apple become the Green Apple? Can New York City, famous for greed, power and exploitation, maintain its position as the “Capital of Capital” while becoming environmentally sustainable?

Well, yes. That’s the plan, anyway—the plan announced by Mayor Bloomberg last year: PlaNYC 2030. As a longstanding green architect, I’ve watched the city’s design policies slowly change over the last quarter century. Rest assured, we New Yorkers are now at least questioning the wisdom (sapientia) of our nastiest habits (roughly, doctrina).

My architectural education took place in the oil-shocked solar 70s, but by the time my partner and I built our first “green” building—a high-tech factory making photovoltaic (solar-electric) panels in Port Jervis, N.Y.—Reagan had removed Carter’s solar panels from the roof of the White House.

Oil prices in America declined and interest in solar architecture waned, except on East 42nd Street, where in 1983 the United Nations appointed a commission to study global sustainability and economic development. The Brundtland Commission issued its landmark report in 1987, which led to the Kyoto Protocols 10 years later.

Despite the lack of interest among New York architects, my partner and I became fascinated with green architecture. Kiss + Cathcart became a leader in sustainable architecture, specifically the building integration of photovoltaics (BIPV), which honestly wasn’t saying very much at the time, since we had very little competition. Until recently, most of our work wasn’t here in the city, but in Europe, Asia and California, where our expertise found more interest.

Over the last decade, Americans have discovered that oil and climate don’t mix, and now sustainability is all the rage. Amidst the confusing editorial exhortations, advertising claims, design solutions and policy prescriptions, carbon is emerging as a convenient index of energy conservation, oil dependence and climate risk.

Some regions have controlled carbon emissions quite well. California, struggling with haze and energy prices, has done very well. The United Kingdom looks good because Thatcher weaned the English from coal. Germany looks good because eastern Germany once looked so bad. Some cities have done well: Curritiba, Brazil; Malmo, Sweden; and yes, New York, N.Y.

The typical New Yorker emits less than one third of the greenhouse gases emitted by the typical American. Although this distinction may feed New Yorkers’ congenital superiority complex, much of it is undeserved. Our port facilities are in New Jersey, and we have little agriculture or heavy industry. To our credit, we are efficiently packed together, and we have an extensive transit system running at about 500 passenger miles per gallon. Of the carbon emissions that remain, nearly 80 percent are emitted through buildings.

In the mid-1990s, some very smart people in city government began studying ways to optimize New York’s inherent energy efficiency. By the end of the decade, the Office of Sustainable Design had issued High-Performance Building Guidelines for the design of public buildings.

Our firm’s design for the DEP’s Brooklyn Central facility rising on Remsen Avenue in Canarsie is a good example of a “High-Performance Pilot Project.” It replaces a LaGuardia-era facility with a giant structure extending over a full square block that captures rainwater for use in the structure and sports a skylight system integrating photovoltaic panels. The lights will need never to be turned on during the day, and most of the building’s base power systems will run from sunlight.

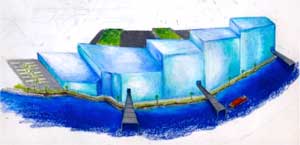

Despite the architectural profession’s inherent conservatism, we practice green architecture for the fun of it. The results are often interesting and rarely predictable. An example: With some research partners, we are now working on vertically integrated greenhouse technologies. We’ve found that although California’s produce is delicious, it’s absurd to transport it all the way across the country. There is no good reason New Yorkers can’t grow all the food we need right here. And these leafy new buildings would be gorgeous.

How to teach this? On one hand, my students must, of course, achieve excellence in what society routinely expects of its architects: the ability to think in three dimensions. On the other hand, my students in “Environmental Design” and “Designing the City” have proven themselves more-than-willing accomplices in questioning urban environmental conventions.

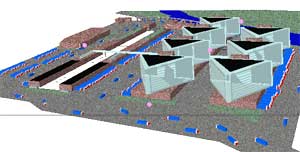

In fact, when the executive and facilities directors of the Hunts Point Terminal Market visited Fordham to review the results of a semester study in design and nature, they were pleasantly surprised to see the students not only proposing “out-of-the-box” design solutions to their traffic, storage, phasing and energy problems, but proposing they grow a good proportion of the food they sell, too.

The potential for New York’s buildings to save tremendous amounts of energy was one motivation behind PlaNYC 2030, but the other was a recent projection that New York City would grow by nearly one million residents by 2030.

PlaNYC 2030 foresees a denser, greener, bigger and healthier city. Important components include generating cleaner energy; phasing-in efficient taxis and construction vehicles; planting one million carbon dioxide-absorbing trees; maintaining and building new transit, ferry and biking infrastructures; and building a lot of housing along subway corridors and on cleaned-up waterfronts.

Since buildings emit most of New York’s carbon, they get special emphasis. Public ratings, energy audits and renovation incentives will induce most owners to retrofit their buildings by 2030, while tighter codes and high energy costs should compel the rest. The city government’s buildings will lead by example, cutting emissions by 30 percent on a crash schedule—not by 2030, but by 2017.

In the spring of 2007, Mayor Bloomberg challenged New York’s big universities to join the city in reducing carbon emissions by 30 percent in 10 years. One of the first to sign on was Fordham.

I’m not privy to Fordham’s plans, but I imagine they will replace much of the University’s aging central plant, install sophisticated building energy management systems, and perhaps even turn the Ram Vans into a dual fuel or hybrid fleet. The administration may call on faculty and students for help in conserving energy, and I hope we will all pitch in.

Faculty members, for example, might consider calling Facilities if a classroom is too hot and stuffy this winter (they won’t take offense; they’d prefer not wasting money making you uncomfortable). As for students, well, at the risk of sounding like your parents: turn off the lights; don’t use the TV as an ambient noise-maker; stop monopolizing the shower; eat your peas and carrots, please… and check back in 2017 to see how we’ve done.

By 2030 New York City may be noted not only for its wealth, but also for its environmental quality. And how will a city of buildings become green?

Primarily, with its architecture.