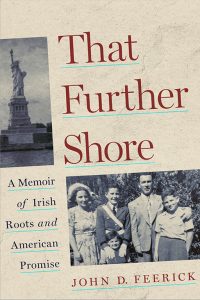

On April 21, John D. Feerick, dean emeritus and professor of law at Fordham School of Law, published his long-awaited memoir That Further Shore: A Memoir of Irish Roots and American Promise (Fordham University Press, 2020). The book details Feerick’s remarkable life and career, from his upbringing as the eldest child of Irish immigrants in the South Bronx to his central role in framing the U.S. Constitution’s Twenty-Fifth Amendment to his two decades of leadership as dean of Fordham Law.

On April 21, John D. Feerick, dean emeritus and professor of law at Fordham School of Law, published his long-awaited memoir That Further Shore: A Memoir of Irish Roots and American Promise (Fordham University Press, 2020). The book details Feerick’s remarkable life and career, from his upbringing as the eldest child of Irish immigrants in the South Bronx to his central role in framing the U.S. Constitution’s Twenty-Fifth Amendment to his two decades of leadership as dean of Fordham Law.

In honor of the book’s release, Fordham Law Dean Matthew Diller interviewed Feerick in a conversation that was streamed live on April 23. And on May 27, Joseph M. McShane, S.J., president of Fordham, swapped places on with Fordham Conversations host Robin Shannon to interview Feerick for WFUV. In a conversation produced by Shannon and coordinated by Fordham Law clinical visiting professor John Rogan, the two discussed Irish history, Feerick’s family, and his extensive career as a lawyer.

Listen to the interview at Fordham Conversations.

Joseph McShane: Good morning, I’m Father McShane, and I’ve been asked to be the guest host for Fordham Conversations. I must tell you I was very honored to be asked to do this today because it gives me the opportunity to have a long conversation with a dear friend of mine, one of the most respected and loved members of the Fordham community, John Feerick, who had, as many of you know, a legendary run of 20 years as the dean of Fordham Law School. After many years of people asking him to put his thoughts down on paper in the form of an autobiography, he has finally done so. The autobiography has a marvelous title, it comes from Seamus Heaney: “That Further Shore: A Memoir of Irish Roots and American Promise.” It is my honor now to introduce to you all for a conversation, JF.

John Ferrick: Thank you very much, Father.

JM: John, I must say when I was asked to read your autobiography, I accepted not the challenge, but the gift of the opportunity very eagerly. But I have to tell you at the outset, I wondered how would this man, who has spent a lifetime in service doing extraordinary things, but always being a man of great humility, how is he going to write and autobiography which will give us all a sense of who he is and what he had done?

And in the book, I have to say, John, you are yourself. That is to say, you tell a wonderful story, but you always point to other people. You rarely, if ever, allow yourself to be center stage here. I say that at the outset and my cousin, who did the introduction, said something similar. This is a man who has really spent his life doing good, but quietly and unobtrusively. So I’m glad that the autobiography is out and I’m also glad I have the opportunity to tease a few things out if you don’t mind.

JF: Thank you.

JM: John, I’m going to start at your beginnings, which are beginnings that actually pre-date your birth. You go into a great deal of detail in the early part of your autobiography about your Irish roots. From County Mayo, God help us. Your great love for your mother and your father. Could I ask you, how deeply did the Irish nature of your family and your upbringing influence you in those key formative years in grammar school and high school down in Melrose, especially in St. Angela’s Parish? How did all of that play itself out in your life?

JF: It probably plays itself out in a lot of ways. Love of family, love of doing good to the extent you can beyond your family. As I think back on my youth, there was so much happiness in the home, even though my father was away during most of the war years. There was Irish music in the home. There was a constant reminder to us that we had a family in Ireland. My parents never saw their parents again after they immigrated from Ireland. But we were conscious of my mother sending clothes and other items to her family in Ireland. My mother sang and danced. My father played the concertina, which I called an accordion in those years. Their Irish friends came over. There was a joy in the home. There were pictures up on the wall, and one was of somebody wanting to go home. I always thought that reflected my mother thinking of her family in Ireland and my father thinking of his family in Ireland. So my Irish roots really were all over me.

JM: John, I have to say there are sections in the early part of the book where you talk about life in Melrose that had me rolling on the floor laughing. The reason is, it was so similar to the experience that my family had living in the Bronx. Mom and dad playing their roles very, very well. Your mother being the playful disciplinarian and your dad watching over everything, more bluff than anything else, more love than anything else. It was a home in which love was really the language spoken and the atmosphere that prevailed.

There also seems to have been deep faith that you picked up and made your own. You talk about the Ursuline Sisters, you talk about being a student at Bishop Dubois High School with the diocesan priests and the Marist Brothers, you talk about that strange moment where you had to decide, “Am I going to take the offer from Dubois or am I going to take the exam for Cardinal Hayes High School?” And you threw your lot in with Dubois. But through it all there is this marvelous presence of deep faith, and it seems to have come naturally from your home environment.

JF: Well, it certainly came from the environment in my home. We said our prayers at night, we kneeled down. And there were expressions of our faith on the wall and right around the corner. The St. Angela Merici Parish church was a short walk up Morris Avenue from my family’s home on East 161st Street. There were constant reminders of our faith as Catholics. We went to confession on a very regular basis. It was everywhere. My parents expressed the faith and my education, as you point out, was with the Ursuline Sisters. And I became an altar boy at St. Angela Merici parish. I was surrounded, you might say, by a reminder of who I was as a boy and as a member of the Catholic faith.

JM: In describing your own life and your own way of proceeding—and this where the marvelous self-deprecation of JF that we’re all familiar with comes in—you say, “I was a person without much focus and, therefore, early on I began to not have the ability to say no, which has resulted in my being such a volunteer. When someone comes to me and asks for help, I can’t really refuse.” This seems to be, John, from your earliest years, one of the great distinguishing characteristics of your life.

Everyone looks to you for help and everyone looks to you for advice. John, you’ve never been able to escape this openness to service. How do you explain that? This great openness to service that you have shown throughout your life?

JF: In the course of doing the book and looking back, I realized there’s a word that describes a lot of it: restlessness. It was a restlessness on my part. I did all kinds of part-time jobs from my earliest years: shoveling snow, delivering groceries, making Italian sandwiches, delivering newspapers. It was a way to make a few dollars, get tips or get some candy bars from Moe when you delivered the papers on Sunday. Opportunities flowed for young children to do things and to receive some recognition. I did that right through high school, right through college. I was used to doing a lot of things and enjoying what I did. When I entered Fordham Law School, I continued to work in the supermarket for my first year, including during the summer when I worked in a law firm in the afternoons. So I just carried that variety and diversity, and there was nothing I did that I could recall now that I didn’t enjoy doing. That’s what I brought to the practice of law.

JM: John, just as an aside, I have to point out something that I picked up in the book. Here you are an immensely successful man in the world of law, in the world of academic administration, in the world of government and politics, immensely successful. But at every turn in the book, you always seem to be a little surprised that you’re successful, such as when you land the job at Skadden and when you’re sought out by governors. Nobody else is surprised because of who you are in many ways. I say this on behalf of everyone I know: you define goodness, you really do, and selflessness. And you’re also a wise, wise man. I just want to say that because you’re so loved that it has to be said. I don’t know if you’ll even accept it. I know you’re Irish and I’m Irish, and, therefore, we turn away from those things.

You opened a door. You said “Fordham,” that magic word for you and me. What was your experience like as a student at Fordham College and as a student at the law school? You mentioned a few of your Jesuit mentors in the book, what was their impact on you?

JF: As I entered Fordham College, my existence was limited to a few blocks in the Bronx. Even though I went over to Dubois High School in Manhattan by bus or trolley, my life was 161st Street and 162nd Street up to the Grand Concourse and Yankee Stadium. That was my village. It was a very, very small village. That was my world. And when I went to Fordham College, it was a totally new world of priests and lay teachers who cared deeply for their students. There was a sense of community at the school. We loved our sports teams. I got involved in the booster club by my late classmate Bob Bradley. We used to go out to New Jersey to watch the basketball team play. There was a larger world that opened to me at Fordham College. Of all my school days, that was my most peaceful period of time where I saw things I never saw before. The Constitution of the United States, for example. I had fabulous teachers.

My faith was developed. We took 24 credits of philosophy and theology. I had theology and philosophy every year, so it was a constant nourishment of the faith I grew up with in the home, but at a different level.

I met lifelong friends, like Joe Hart whose burial I was at yesterday. I was asked by a Jesuit priest at the cemetery to say something. I said, “At Fordham College, I met such wonderful classmates and some remain lifelong friends of mine.”

The values of my faith and the values of service came home in a bang for me at Fordham College. I was asked to be a class representative in my second year, then vice president of my class in my third year, and then vice president of the student body in my last year. The notion of serving others came home in a big way because of the opportunities that came to me. And none of us were looking for another position, we had opportunities in our present positions to do all you could for your class or the school.

It was wonderful, and I describe in my book how Fordham College and then Fordham Law School impacted me. Fordham Law School was different. It was buckling down in terms of rigor, certainly in first year of law school. We loved our teachers and most of us worked part-time after classes. Because of Fordham College, I had developed an academic record that I didn’t have in high school and grammar school. All of a sudden, I seemed to come alive academically at Fordham College, and that continued right into the law school. I remember during college writing papers on subjects like separation of powers. I used my paper on that subject for testimony I gave to Congress on why the 25th Amendment should be adopted. I was introduced to the concept of separation of powers at Fordham College in my government courses.

I had Father McKenna as a teacher in three or four classes, he eventually, as you know, went to Nigeria. I had lay teachers and members of the Society of Jesus who educated me, not only the basic first or second year of the curriculum, but also in the third and fourth year. I am what I am thanks to my parents and thanks to all those who were my teachers and role models and mentors in so many different ways.

JM: John, you went from the law school to the law firm of Skadden Arps. Even as a very young man, you played a major role in constitutional law with your work on the 25th Amendment. You became overnight an intellectual force and a legal force to be, if not reckoned with, always considered, including in the last few years, and you’ve worn that mantle with dignity and with restraint. But you do know you really are an extraordinarily important figure in American jurisprudence and American political life as a result of that, you do know that I hope?

JF: Well, I don’t feel that. I’m surprised at times when the library at the law school tells me that the book I wrote on the 25th Amendment and also my earlier book on presidential succession are the basic source books on that subject today. I had the opportunity to work on the 25th Amendment as a very young lawyer because I had written an article for the Fordham Law Review on the subject of presidential inability. When President Kennedy died, it was the most recent article on the subject. I had sent reprints before the assassination hoping to interest people in solving a problem that I had learned about. I would have never had thought that the article would have led to my involvement with a group of former attorneys general and very distinct lawyers in crafting an amendment to the United States Constitution.

I had no sense as I was working on it that it was something that was going to be in the United States Constitution. You were hoping, you were doing everything you could to persuade Congress and others about it. I was just working away and hoping, not expecting, that all of a sudden this was going to go into the Constitution because people had been working on the problem for 100 years. But it got solved at that time because of the assassination of a president and great leaders in Congress of both parties. Congress worked together and they allowed a number of us, including myself, an opportunity to make suggestions and even contribute language that’s in the Constitution today.

JM: An extraordinary achievement and, yet again, John, you characteristically throw the spotlight on others. But it is a great gift to the country thanks to that fine mind you developed at Saint Angela’s and then at Dubois and then at Fordham College and the law school. And everyone is in your debt, not just Fordham, but the whole country’s in your debt.

John, I’m going to go to a conversation that you had, if you don’t mind me doing this, with Father Finlay in 1982. A common man born and raised in Manhattan approached a Mayo descendant raised in the Bronx and placed before you what he later told me was the boldest thing he had ever done, but also the cleverest thing he had ever done. He told me about the conversation he had with you about giving up your career at Skadden and becoming the dean of the law school. Do you remember that?

JF: I can’t ever forget that. I have tears in my eyes just thinking about it. He was just a lovely Jesuit who I had met when he was teaching political science at Fordham College. He had asked me to do a class, I think even before the 25th Amendment was in the Constitution, on the subject of presidential inability. My wife came with me to the class. And then years later he asked me to go on the Board of Trustees. He was such an important part of my life. I thought the world of him.

I received a call from him after Dean McLaughlin announced that he was leaving. I had been president of the law school’s alumni association for a number of years for Dean McLaughlin and he had a major influence on my life. Father Finlay and I sat down at the University Club and he asked if I would consider putting my name in for the deanship of the school. In words and substance, he told me how important the law school was to the Society of Jesus. He asked if I would consider coming over and helping develop a vision for the future law school. That was so empowering to me, especially because I had the experience with Dean McLaughlin being involved in the life of the law school and then as a trustee of the University from 1978 until that conversation a few years later with Father Finlay.

It took me a while to process the offer. I was a senior partner at Skadden Arps in years of service, the chair of its hiring committee of lawyers, and on its executive committee. And I said to myself, “Well, if you leave, you’re not going to return.” At the same time, there was something within me that said, “This is your time to embrace full-time, not part-time, an opportunity to render service.” My decision to serve as dean went beyond any service I had done in my life. My father was shocked, I would say, by my decision from an economic standpoint. My mother was beginning to decline and lose her memory at that point, and I don’t know if she quite absorbed what was happening. My wife was very quiet, but I had a sense that in her quietness, she was hoping I would make that decision believing, in part, that I would have more time for her and our six children.

So on the day of the deadline to apply for the deanship, I talked to Professor Joseph Sweeney, who chaired the committee looking for a new dean. I said, “I would like to put my name in for the deanship.” Then on December 8, the Feast of the Immaculate Conception, I remember coming home from mass and Emalie saying to me, “Father Finlay called you.” I said, “Uh, oh.” I called him back, and he offered me the deanship.

Being dean just had such a profound impact on me for the rest of my life, up to the present time. In fact, at yesterday’s burial service in Boston of my longest friend, Joseph Hart, the priest there in his few words said, “I understand there’s with us today a friend who was dean of Fordham Law School, and he and Joe had this special relationship.” So even as a former dean you have an acknowledgment, I suppose, of one’s service as dean. And, Father, you’ve been extraordinarily generous giving me the title of dean emeritus. It was a great part of my life. Nothing like it.

JM: John, I should tell you that Seamus, Father Finlay, when he recounted the story, told me that he chose to call you on December 8th knowing that you’d be coming home from mass and, therefore, you’d be most vulnerable. And you accepted on the spot and made his life much easier, much happier. You and I know this, he was a perfect gentleman and a very fine priest and an exemplary Jesuit. He would say that getting you to become the dean of the law school was the crowning achievement of his presidency, and all of us would agree.

John, you took the law school from what was a strong law school, from what was seen as a good, city, meat and potatoes, law school, and you made it a force. You brought it up to new levels. You hired boldly and wisely and well. You encouraged people in their teaching and in their research, and you defined the culture in a new way. It was during your time that the law school adopted a very clear motto and mission. You were the man who told Fordham lawyers that they were to be in service of others, no matter what else they did. As you and I know, that is the mantra that is now deep in the hearts of everyone in the law school and anyone who’s ever gone to the law school. From the moment they entered, that is what they are challenged to be. Not just good practitioners, although you were insistent on that, but lawyers who recognize that life is not complete, you would say, unless it is adorned with service.

Then time and time again, governors turned to you. I know that you had two New York state commissions on government ethics and many other public service roles. You became, for everybody, the go-to guy, the honest man, the honest broker who could be trusted with the most extraordinary things, the most difficult problems, that the city, the state, the profession could face. And you did these things, you took them on and you brought them to completion successfully. You’ve had an impact well beyond the law school. I think this is a great part of your life and a great part of your legacy. I know from all the conversations we’ve had and from reading your autobiography that this is important to you. It goes back to your philosophy that the inner man and the outer man has to be one. Let the inner man be generous and the outer man will show it. Am I misconstruing what it is that you’ve been doing all these years to such effect and so humbly?

JF: There’s so much you’ve just said, Father. I guess I would just say, as to the law school, the best thing I did as dean was to develop an approach to governing that was consensual in nature. Listening to faculty, listening to administrators, listening to the alumni, and hearing so many ideas and suggestions, especially the faculty’s desire to see their respective areas grow. In my position, I was able to support and encourage so many different people who had ideas. They weren’t my ideas flowing down. I got ideas from listening to people. The transformation, as it might be described, of the law school over the last two decades of the last century is really a tribute to hundreds and hundreds of people who served the law school full-time and the alumni of the school who supported, time and again, all of those initiatives. As I say in the book, I was a lucky person to be in a place where I could be part of it.

As to all the commissions, how I disliked doing that kind of work. I didn’t grow up as a prosecutor or in law enforcement as such. I learned you have to take the hits when they come, criticisms when they come, and, at times, affirmation about work that’s been done. I kept seeing the values of Saint Ignatius. I told myself, “Get out there and do the work, and don’t be looking for credit. Just do what’s right and what’s good as you see it.” I held that as I dealt with low moments and high moments. I was constantly reminded of those values. And that’s really what I aspired to express in whatever way that I could in doing all of that work.

I followed the work of Robert Mueller in Washington, and I saw in him a person who had a life of devotion to law enforcement, as FBI director, as a US attorney. Judge Patel, a Fordham Law graduate, knew him very well when she was the chief judge of the federal district court out in San Francisco. She used to describe him to me as a model. When he ran into those difficult moments of being criticized by people upset with the investigation, I understood what he must be feeling, I think, because in a smaller way, in a different way, I experienced similar situations chairing those state commissions. Looking back, I have no regrets. I did my best, and believe that some of the work of the commissions, which involved a lot of commissioners and a lot of people, have improved the ethical climate in New York state to some extent.

JM: There’s no doubt about that, John. Our time sadly is going to come to an end. I’m going to ask the most difficult question of someone like yourself, because you don’t even know how to spell the word “pride” or the word “proud.” But, John, what is it that you’re the most proud of as you look back on what could only be described as a storied career, a stellar life. What are you most proud of?

JF: I would say maybe three things, if I could have a multi-faceted answer. First, I’d certainly include becoming involved in the cause of an amendment to the Constitution to deal with the problems of presidential inability and vice-presidential vacancy. When I was on the ground working on it as young person, I didn’t fully realize the importance of the moment.

Another moment was when I became a dean of the law school and the law school had an aspiration of doubling the space basically at 140 West 62nd Street. There were those, like Jesuit Brother Kenny and others, who said, “There’s no way the law school is going to raise the money to cover the cost of doubling of the space.” I took that as a challenge. I got the alumni and others involved and, ultimately, we made it happen. Father O’Hare came along and was very supportive of us financially. I think we had a debt of $2 million or so to the University when the costs were all in, and I remember meeting the faculty with Father O’Hare and others. I said, “Father, based on the contributions, so to speak, that we’ve made is there any chance that I can get that debt off the law school?” And he said, “That’s a good idea, we’ll do it.” But it was that project, the doubling of the size of the law school, that certainly was a high point for me. I think it gave me credibility because a lot of people thought it couldn’t be done. But the whole community came together and my job was to go all over the place to seek support for it.

The third thing I’m proud of is the relationships I developed with all of the young people that I came to know when I was dean of the law school. Anybody who wanted to come and needed help, my door was always open for them. There were students who came in and cried because they couldn’t find a job. There were others who came in because they couldn’t afford tuition at the law school, but thanks to the caring community that I was a part of we were able to respond and able to help. If I put all of those individual meetings and opportunities together, that would constitute the third thing that I’m proud of. I don’t feel comfortable with the word proud, I’m just glad that I had the opportunity to be there in times of need for other people.

JM: John, I acknowledge at the outset that it was going to be the most difficult question because pride doesn’t figure in the way in which you live your life. I’m going to say two things, if I could. I think that your letter to your grandchildren, which is at the end of the book, should be required reading for anyone’s grandchild. It’s filled with, I would say, balance and wisdom and great love. It’s kind of like the exclamation point at the end of the book and I want to thank you for that.

John, we’re going to have to stop because time has run out. I could go on with you for days, not just hours, I could go on for days with you. My last word to you is this: I know I speak for everyone, for all of us who know you, we are immensely grateful for your presence in our lives. We’re grateful for your wisdom, the constancy of your devotion and the fact that to know you is to be ennobled. And you have to know that.

JF: Father, if I could just bring it to a close. I appreciate greatly what you just said, but I’m a small part of a University that has enjoyed great presidents and you are truly a great president. And your predecessor, Father O’Hare, was a great president. Father Finlay was a great president. And when I was a student, I so admired Father McGinley. He used to walk around the campus saying his prayers, and when he was no longer the president he came to a lot of alumni gatherings and we always found each other and spoke.

I’m a small part of an institution that has truly giants and great priests who serve humanity far more than the kind of things that I’ve done. Their reach is so majestic. I thank you, Father, for your presidency of Fordham University at a very difficult time. I also thank you for your masses, your readings, and your reflections, which have been empowering for all of us who are trying to get meaning in the present moment. You’ve helped us and I thank you.

JM: John, thank you very much, you don’t know how much that means to me to hear you say that about Seamus, and about Larry, and about Joe. I am not worthy to be in the same sentence with any of them. But I want to go back and have the last word. John, you’re for us a source of enormous pride because you live with such integrity and you ennoble everyone that you meet. And with that, John, thank you very, very much.

JF: Thank you.