“Think about that question,” said Father Massingale, the James and Nancy Buckman Chair in Applied Christian Ethics at Fordham. “Why is it that the only group that’s never supposed to feel uncomfortable in discussions about race are white people? … We have to face the fact—and this is what I try to get at in my essay,” he said, referencing his recent op-ed in the National Catholic Reporter, “is that the only reason why racism still exists is because it benefits white people, and there is no comfortable way of saying that.”

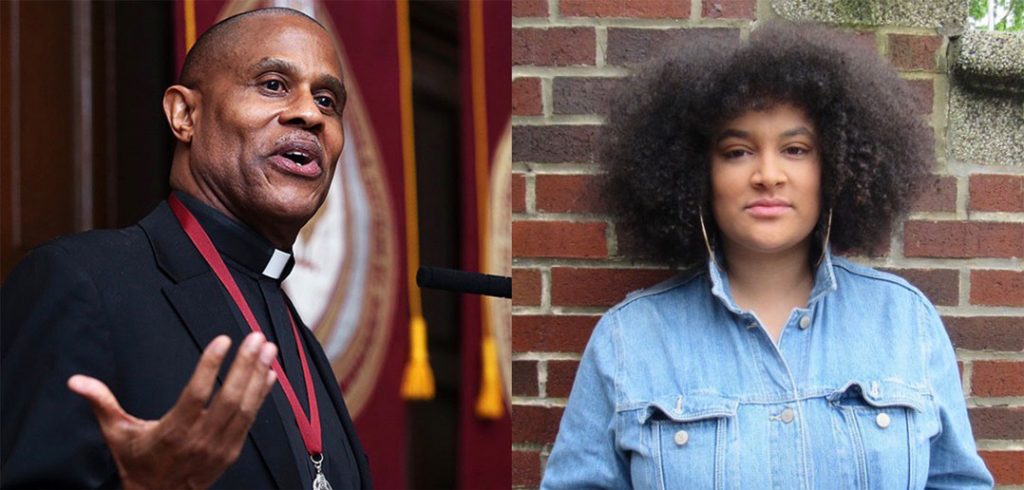

In an hourlong online conversation on June 4—amid national protests against police brutality and racial injustice following the death of George Floyd at the hands of Minneapolis police—Father Massingale spoke with Olga Segura, a 2011 graduate of Fordham College at Rose Hill and former associate editor of America Media, on how systemic racism impacts the church and how fellow Catholics can help dismantle it. John Gehring, the Catholic program director of Faith in Public Life, a national network of nearly 50,000 clergy and faith leaders, moderated the discussion.

In his book Racial Justice and the Catholic Church (Orbis Books, 2010), Father Massingale reviews and analyzes the major statements on race that the church has made since the 1950s and offers recommendations to improve Catholic engagement in racial justice.

“It’s not true to say the Catholic Church has said nothing and done nothing. But what the Catholic Church has said and done is always predicated upon the comfort of white people and not to disturb white Catholics. And if you make that your overriding presumption and goal, then there are going to be difficult truths that will never be spoken, and we will never have an honest conversation,” said Father Massingale, who teaches theological and social ethics at Fordham.

The online forum began with a recollection of recent events, including not only the killing of George Floyd but also the recent death of another Black man, Ahmaud Arbery, who was shot and killed while jogging through a Georgia neighborhood, and an incident in Central Park in which a white woman called 911 to report that an unarmed “African American man” who had asked her to comply with the park’s rules to keep her dog on a leash was “threatening” her life.

“That all moved me to the sense of, how long, how long do we have to continue to endure the humiliations and the terror that come with being Black, brown, other in America?” said Father Massingale.

These are things that are especially important for white people to hear, said Gehring.

“Part of white privilege, as you all know so well, is the ability not to have to think about this. I’m someone who’s tried to learn as much as I can about the history of the United States, but I will never know what it means to be a person of color in this country,” he said.

In their conversation with Gehring, Segura and Father Massingale made several points about how Catholics and others can acknowledge white privilege and confront racism on a personal and institutional level.

Racial injustice is a pro-life issue. In a recent statement, Pope Francis said Catholics cannot “tolerate or turn a blind eye to racism and exclusion in any form and yet claim to defend the sacredness of every human life.”

When asked to comment on the pope’s statement, Father Massingale said, “At last, someone in high authority has been saying what people of color again in the Catholic Church have been saying for a long time—that racism is a life issue.”

For too long, “we’ve framed concerns of pro-life around a very narrow meaning of being anti-abortion,” said Father Massingale. But it is impossible to support policies—in education, health care, and criminal justice, for example—that are “detrimental to the lives of people of color, and yet call ourselves pro-life,” he said. Segura agreed.

“As Catholics, we’re doing a disservice to ourselves and our church when we say we’re pro-life, but are unwilling to sit with the most significant civil rights movement since the ’60s,” said Segura, who is writing a book on the Black Lives Matter movement and the Catholic Church.

Racism is a religious and spiritual challenge—not just a political issue. The civil rights movement was successful because it spoke with moral authority, said Father Massingale. To show their support for racial justice and solidarity with people of color, Catholic bishops could visit “shrines that we’ve erected where Black lives and bodies have fallen and lead a rosary there,” he said. And Catholics don’t need to wait for bishops to act. Bishops “bear a unique symbolism and responsibility,” but lay activists and leaders should participate, too. By bearing witness and walking with their Black brothers and sisters, they can send the message that “you cannot be a good Catholic and not be concerned about what’s happening here,” he added.

Put yourself in another person’s shoes—and ask your friends and family to do the same. A good way to do this is through Ignatian spirituality, said Father Massingale. “If we use the tools of our contemplative traditions, whether it’s Ignatian or Carmelite or whatever, and have people dwell there, that’s when you have affect and faith meeting. And that gives us the tools, the possibility for a breakthrough—a breakthrough that won’t happen if you try to engage in talking points,” he said.

One example is to imagine what it’s like to lose your child in a retail store, said Father Massingale, who once worked in retail store security. “Parents would come to us in a panic,” he recalled. “The joy, the relief … you could see people begin to breathe again when you’d reunite them with their kid. … And the kid was only gone for a matter of minutes.” He urged the audience to ask their family members to imagine another situation: what it’s like to have your child shipped out of the country, with no idea where they are.

“To just sit in that agony, to sit in that desolation … I can’t imagine what it’s like to be a parent and to even contemplate that,” he said.

Be careful of polarizing people, but hold them accountable. Segura said she has seen lists that separated Catholic parishes into those have either recently addressed or not addressed racism. She urged people to publicly speak about where parishes have succeeded and failed. “If you see that your priest has not mentioned race once this month or in May, talk to him about it,” said Segura.

Our national policing culture is broken. “We need to make a crucial distinction between supporting police officers and reforming the culture of policing. Too often we get distracted by saying that if we criticize the police, then we’re denigrating the good, law-abiding officers,” said Father Massingale. “We need better guidelines to train our officers on the appropriateness of lethal force, when it’s appropriate to use it, how to train people on de-escalation procedures, but then also create those mechanisms that can hold officers responsible when they abuse [their power].”

To fight against police brutality, we also need to educate ourselves and demand that our local leaders are transparent about the funding behind police departments, added Segura.

Listen to people’s sadness and grief. “We, as persons of color, we have marched, we have demonstrated, we have petitioned, we have boycotted, we’ve voted, we’ve written op-eds. We’ve bled, we’ve prayed, we’ve begged, we’ve pleaded, and we’ve done that for years, for decades, for centuries,” said Father Massingdale, “and still we’re in a country where a Black man can’t go jogging without being stalked and killed.” He stressed that he doesn’t advocate violence. But he added that not all of the violence done by protestors has been “done by people of color,” and in some places, there is more concern about violence done to buildings than violence “that’s been inflicted on Black and brown bodies and Black and brown communities for so, so long.”

The pandemic also makes it more difficult to grieve, especially for people of color who have been disproportionately affected by the pandemic, Segura said.

“Many of us have been reporting and talking about [racial injustice] for years, but this is the first time where I’m forced to try to reconcile with what it means to privately grieve with my community, privately grieve with my family at a time when we cannot physically be together,” she said. “We have to rely on phone [and video] calls. Black and brown Catholics are very much about being in physical community with each other. So what does it mean for me to try to grieve everything that’s happening at a time when we can’t be together?”

To enact change, we must engage in a relay race. Segura said she has been inspired by Father Massingale’s work, particularly Racial Justice and the Catholic Church, which she said helped shape her faith and her understanding of what it means to care about racial justice in the church.

“If you hadn’t written your book, I would’ve found it very hard to write my book in 2020,” she said to him over the live video chat.

Father Massingale said it is wonderful to see someone so young and energetic add her voice to their ongoing struggle.

“I’m not going to live forever. … I’m probably going to pass on before we reach whatever racial promised land we’re coming to,” said Father Massingale, who is 63 years old. “But I do what I do for the sake of those who both were ahead of me, to honor their work, and for those who are coming up behind me—people like Olga and so many others. … It’s going to be an intergenerational process. But we have to start now.”

The full recording of their discussion can be viewed on Facebook.