In a joint lecture to approximately 25 students, faculty, and staff on March 7 at the Lincoln Center campus, Christiana Zenner, Ph.D., associate professor of theology, and Leslie Timoney, associate director of campus operations at the Lincoln Center campus, illustrated why there is much more to water than just H2O.

An Engineering Feat

Timoney, who spearheads the Lincoln Center campus efforts to meet the city of New York’s Water Challenge, explained how the city first began collecting water in a reservoir at what is now Bryant Park, and then, as the city grew, began expanding its water system into the Catskill Mountains region. The current system consists of a series of aqueducts, reservoirs, and tunnels that funnel drinking water from the Croton, Catskill, and Delaware watersheds toward the city, with one last stop in Mount Pleasant, where it runs through a facility that uses ultraviolet light to disinfect it.

“Amazingly enough, [the system is]125 miles long, and water gets to the city 95% by gravity. We’re only pumping 5%. It’s just an amazing engineering feat,” she said, noting that most cities spend three to four times more than New York because of pumping costs.

“So this is just a unique situation, and we’re lucky to have it.”

What also makes the water system unique, she said, is the fact that the New York state controls the watershed where New York City gets its water. When New York first began tapping water from the Delaware watershed, west of the Catskills, the state of New Jersey sued to stop it, because the water flowed into the river that divides New Jersey from Pennsylvania. The Supreme Court actually settled the dispute in a 1954 case that dictated how much water each state could claim.

The average New Yorker uses 120 gallons of that water a day, she said. Personal use, such as drinking, cooking, showering, and cleaning, accounts for 60 gallons a day, while the other 60 gallons is used for services, such as street cleaning and restaurant supplies. To help preserve that watershed, Timoney said Fordham has taken actions such as using new washing machines on campus that use significantly less water.

Water As a Right-To-Life Issue

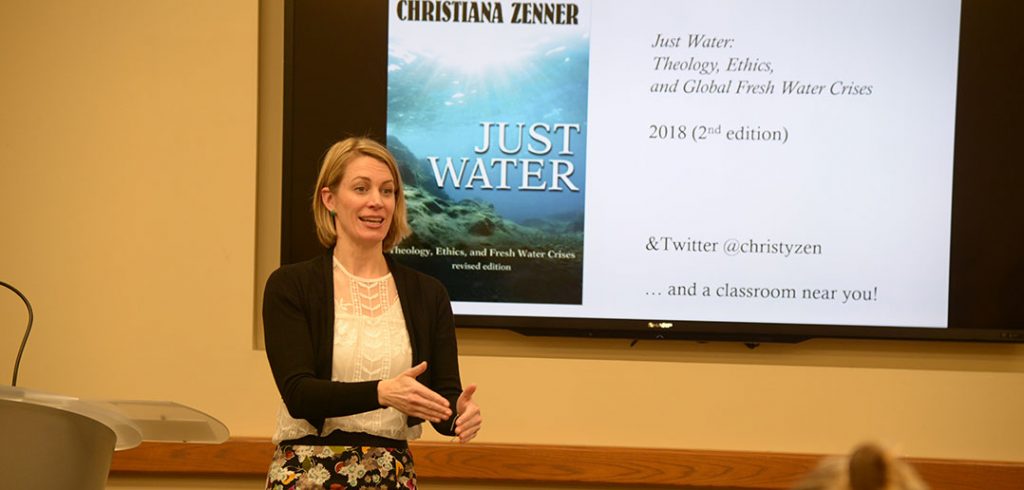

Zenner, the author of Just Water: Water, Ethics, and Fresh Water Crises (Orbis, 2018), said she appreciated the nitty gritty details of Timoney’s presentation, such as the fact that the 14 water treatment plants that treat sewage are connected to both the city’s sewers and its storm drains. The latter fact should give us pause about letting dog waste, litter, or lawn chemicals end up in the gutter, and also get people thinking about the entire water cycle.

“When I give talks, one of the challenges that I often give is, ‘Let’s learn about your water supply. Let’s learn about how the fresh water is sourced, and how it’s treated, and how it interacts or doesn’t intact with other forms of treated water,’” she said.

She said the philosopher Ivan Illich had it right when he declared ‘I shall not reduce all waters to H2O.’

“One of the tricky things in speaking with water policy folks, and why we sometimes look at each other across the table like aliens when we have conversations, is that, for many water policy folks in the late 20th and now 21st century, their presumption has been that water is H2O, and it is an entity that is amenable to various forms of technological, engineering, and economic control,” she said.

“It has been treated as resource and a commodity, but it is also more than that.”

In fact, she said, the current global freshwater crisis has spurred many religious groups to turn to their traditions to ask whether they provide moral reasoning that can inform thinking about water as a justice issue, or as a sacred substance.

The Catholic Church addressed it most recently in 2015, when Pope Francis issued the encyclical Laudato Si’ but Zenner said the church had in fact been quietly but consistently raising access to clean, fresh water as an issue since 2000. Water, she said, is a locus for thinking about “the interaction of social and ecological justice, and the imperative of protecting the environment and providing livelihoods to the poor.”

“Fresh water is seen by the Vatican as a matter of dignity, justice, and respect for life. In fact, this language of water as a right to life issue can be found in a good number of Catholic documents. I stress that because particularly in a Catholic church in the United States, that is a not a standard association of right to life language. If I say right to life, you will likely say abortion, birth control, maybe euthanasia or the death penalty, but not necessarily access to clean, fresh water,” she said.

“So that’s a really important moral expansion to note.”