The year was 1943. The Second World War had been raging for four years, and it would be another two years of vicious fighting before Allied forces would be able to declare victory.

In the United States, subscribers to Life magazine opened up their issues that year and were greeted by a jarring image.

Francis Spellman, New York’s Roman Catholic Archbishop and the Vicar General of the Army and Navy, was pictured presiding over Mass not in the splendor of St. Patrick’s Cathedral, but at a crude, makeshift altar built of large bricks, created for troops stationed in Egypt. It contained a “portable altar stone,” the caption noted, and allowed the cardinal “to consecrate any convenient table where Mass was called for.”

To John Seitz, Ph.D, images like these are perfect examples of the way Americans were telling the world that God was on their side in the war, and that their troops were not depraved or bloodthirsty fighters.

“Americans were increasingly becoming aware of war’s damage on psyches, and they were very nervous about what would happen when all these potentially “damaged” men would come home from the war, said Seitz, an associate professor of theology.

“Religious images were really useful for communicating that they’re not that untethered from tradition, from God, from deep questions, and the things that we practice at home,” he said.

A Tradition Well-Suited to the Task

Seitz, who earlier this year published “Altars of Ammo: Catholic Materiality and the Visual Culture of World War II” in Material Religion: The Journal of Objects, Art and Belief, said that Catholicism was particularly effective at communicating this message, thanks to its overt embrace of materiality.

“When it comes to photography, Catholic ritual forms like elevated arms, long ornate robes, and specific moments of ritual posture among both the leaders and the congregation were really vivid ways of saying, ‘American troops are in tune with tradition,’” he said.

Celebrating religious diversity was a major goal of government censors, he said, and images of Catholics, Protestants, and Jews working together to fight injustice were meant to distinguish the United States from both Nazi Germany and what was seen as an atheistic Japan.

What was surprising about the popularity of these 1940s Catholic images was the fact that the materiality and elaborate rituals that made them so effective were also the reasons mainstream Protestants had been suspicious of the faith for nearly all of American history.

From Idolatrous to Iconic

“A dominant Protestant theory about Catholic rituals is that it’s a crutch, only for weak people. It’s kind of like superstition to have all these kinds of hocus pocus ritual transformations,” he said.

“In theory, at least, Protestants can rely solely on faith. You don’t need any of these ritual elements, you don’t need a priest mediating your contact with God. So, with these wartime images, Catholic images and materiality went from being idolatrous in the Protestant American imagination to being iconic in the environment of wartime propaganda.”

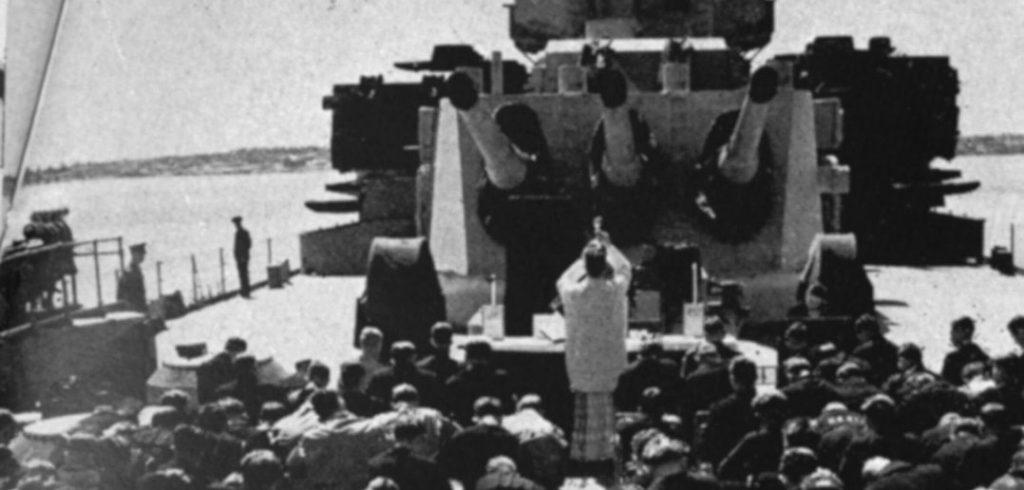

While Protestant America was coming around to Catholicism, thanks in part to these images, the editors of mainstream Catholic magazines that were writing captions for these images were wrestling with the cognitive dissonance of pairing a religion based in love with efforts to promote the war. Seitz noted that in one particularly vivid image of a priest on the battleship that appeared in The Priest Goes to War, (The Society for the Propagation of the Faith, 1945) writers suggested that the ship added to the splendor of the Mass.

“They want to have the guns adding to the grandeur of the Masses, which is a really surprising thing to think about. At that the same time, they want to say the Mass is kind of in conflict with that, and the priest is only there to serve, and not to perpetuate violence,” he said.

“From my vantage point, it’s pretty hard to extricate those things from one another in this context. They can’t quite pull it off, because there they are, reprinting this image and celebrating how beautiful it is.”

Seitz said images like these complicate people’s understanding about what religion is about. He said he hopes his students appreciate the multiple ways that religious ideas and images and objects work in the world.

“There’s a risk that we approach religion as a static, rigid set of ideas you have to agree with or not, when in fact religion and religious objects are malleable, dynamic, and interact with culture,” he said.