It was a combination of the deep empathy and solution-oriented practicality that defined his life, explained Roger Hayes, a friend of Father Brant’s since seminary in the 1960s.

“He cared a lot about people on the margins, but also his rational mind was—we can make this better. We can fix this,” Hayes said.

Father Brant died last month in Mexico at the age of 82. Though he never got to build houses in Peru, he did spend time there, as well as in North Carolina and Chicago. But friends here remember his devoted friendships, deep spirituality, and central role in the birth of the Northwest Bronx Community and Clergy Coalition (NWBCCC), a community power group that has had a transformative impact on the borough since 1974.

“The social doctrine of church says we’re supposed to ‘propose a society worthy of the human person.’ That’s what he was doing,” said Lois Harr, FCRH ’76, an early NWBCCC staffer.

William Frey FCRH ’74, who worked under Father Brant in the first years of the NWBCCC, agreed. “I think he felt it was very much the church’s mission, to give people hope and listen to them and then help them not only be hopeful but to take responsibility,” he said.

Brant arrived at Fordham for his philosophy studies in 1969, at a time when faith in the viability of cities was at a low ebb. Deindustrialization, suburbanization, and two decades of studied under-investment had taken their predictable toll. The Bronx was experiencing the worst of it and the people who lived there were demonized as the cause of the problems.

A young Jesuit scholastic inspired by Vatican II’s call for a church engaged in the modern world, Father Brant wanted to understand what could be done. He was accepted into New York City’s prestigious Urban Fellows program, meant to harness ideas for the city in crisis. Gregarious and forceful, yet able to work diplomatically, Brant had the backing of Fordham’s president James Finlay, S.J., to serve as a kind of unofficial liaison to the Bronx. He helped Fordham see a role for itself in changing conditions in the Bronx, Frey said.

With other young Jesuits—including for a time Louis Mulry Tetlow, father of Fordham President Tania Tetlow—Brant lived in an apartment south of campus, gaining firsthand insight into the scope of neglect and abandonment afflicting the borough.

“Paul felt, well, look, there’s a lot of people still in these neighborhoods. It’s not inevitable that everything gets worse,” said Hayes. “What are we going to do?”

Being embedded in the community and having long conversations with Hayes and Jim Mitchell, another seminary friend, convinced Father Brant that the solutions to the Bronx’s problems would come by directing the power of the people themselves. In 1972 they formed a neighborhood association in nearby Morris Heights using relationships within the parish to confront negligent landlords. Seeing nascent successes there, Father Brant moved to launch a larger group.

In 1974 he convinced pastors from the 10 Catholic parishes of the northwest Bronx to sponsor an organization to fight for the community, and the NWBCCC was born. Soon the group expanded to include Protestant and Jewish clergy. Membership was always nonsectarian. The NWBCCC went on to train leaders in hundreds of tenant associations and neighborhood groups, knit together across racial lines and around shared interests. When they learned that rotten apartments had roots beyond individual slumlords, they picketed banks for redlining. Before long Bronx homemakers and blue-collar workers were boarding buses to City Hall, demanding meetings with commissioners and testifying at the FDIC. With similar people-power organizations nationwide, they won changes in the nation’s banking laws, drove reinvestment to cities, and sprouted a new ecosystem of non-profit affordable housing.

Years later Father Brant reflected on the work of the coalition as being essentially like St. Paul’s description of the church as the Body of Christ—many parts, but one body in concert.

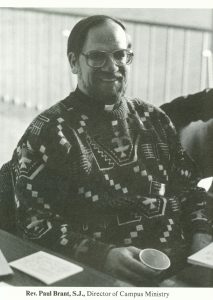

In 1975, Father Brant left for Chicago to begin his theology studies. He was ordained a priest in 1977. He went on to do other work, first finishing his theological studies at the Jesuit School of Theology in Chicago, working at Loyola Chicago and serving as a pastor in that city, then as director of campus ministry back at Fordham in the 1980s and assistant director at St. Peter’s College in Jersey City in the early 1990s. While in campus ministry he led hundreds of students on immersion trips to do community projects in southern Peru. From 1993 until his death he lived and ministered with Latino agricultural workers in North Carolina, his home state. Eventually he also made extended visits to a parish in Mexico, where he worked on projects with the local diocese.

Jim Joyce, S.J., the former director of social justice ministries for the New York province and a longtime friend of Brant’s, visited him in North Carolina in the 2000s. He was moved to see Father Brant celebrate Mass at an altar built into the bed of a pick-up truck he drove out into a field. More than 1,000 Mexican migrants, far from home but together in exercise of their faith, crowded into the field—many parts, one body.

Mitchell, too, saw a continuity in his old friend’s work.

“It was the poorest people in this country that he reached out to, in the Bronx in the ’70s and then in North Carolina. He worked a lot with poor people in ways that elevated them, in ways that made them more self-aware of their dignity.”

—by Eileen Markey