This past semester, Robert Spiegelman, Ph.D., showed students in his “Studies in Social Science” College at 60 class a video clip of the Berlin Philharmonic commemorating Adolf Hitler’s birthday with a performance of the “Ode to Joy” from Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony during World War II.

“I was quite nervous about showing the clip,” said the Fordham College at Lincoln Center and Rose Hill sociology professor. “It ran for about 10 minutes and at the end of it, I didn’t know if I had gone too far in showing it.

“But I wanted the students to see how the worst of humanity can hijack the best of humanity. Beethoven’s music was positioned as perhaps the highest creation in Western cultural history, but it was hijacked by the Nazis, and that was the irony of the performance.”

Looking around the classroom, Spiegelman saw that some of the students were in tears. Others were enraged and saddened by the consequences of the deadliest war in history. Then 100-year-old Holocaust survivor Mathilde Freund, who has been taking courses at Fordham for over 40 years, raised her hand.

“I’m very glad you showed that video,” said Freund, who shared memories about hiding from Nazis at the same time of the performance, crawling in the forests and stables of France with her mother, being captured, and then being tortured in the Montluc prison in Lyon. “Look, how horrible. While they’re performing this wonderful music of Beethoven, they’re murdering millions of innocent people. Unfortunately, my husband was among the people who died at the Buchenwald concentration camp.’”

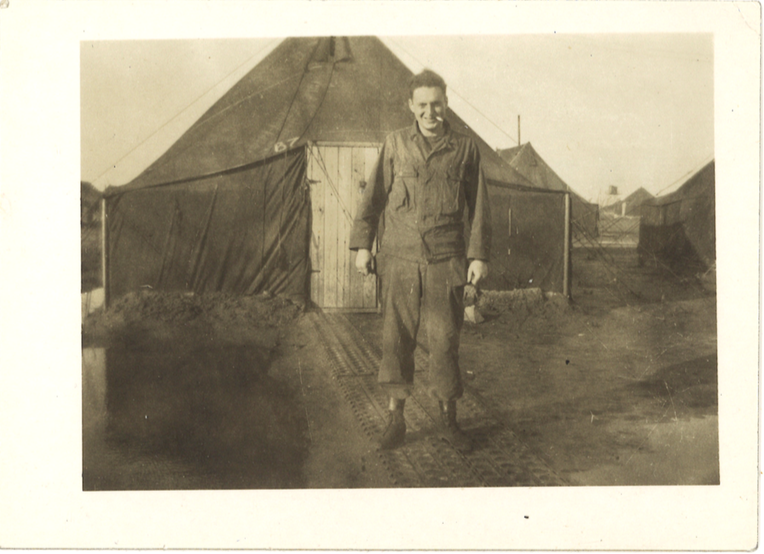

What Freund and Spiegelman didn’t know was that they were connected through this very experience. Speigelman’s father, Seymour, a World War II army corporal, was among the U.S. troops that liberated the Buchenwald concentration camp in Germany after Freund’s husband, Fritz, was killed.

“I think it’s telepathy,” said Freund. “I was interested in this course, but I didn’t know that we would talk about the concentration camp or anything like that.”

For Speigelman, too, this wasn’t a mere coincidence.

“To know that my father was probably within a few feet of where Mathilde’s husband laid just moves me to such great depths,” said Spiegelman, who said his father had been traumatized by what he witnessed. “He wasn’t able to speak about it until years later when I kind of pushed him and he told the story.”

From 1933 through 1945, the Nazi party created numerous concentration camps to incarcerate, torture, and kill Jews and other minority groups. Among them were the infamous Auschwitz in Poland and Buchenwald, one of the largest camps in Germany. Freund, who married her husband in 1937, said within months of marriage her family had to flee their homeland of Austria to France, where the men in her family joined the French Army. While she was in hiding, Freund said her husband managed to send her a postcard.

“He said, ‘I will still survive and when the sun shines, we will be together again,’” she said. “But he was killed.”

Losing her husband wasn’t Freund’s only tragedy. Her only brother was brutally murdered in the Massacre of Lyon on August 18, 1944. In 1952, she arrived in New York with her mother and daughter.

“Some people say we should forget the past and we shouldn’t talk about it, but I say we should never forget because innocent people were killed. It was cruelty beyond imagination. No book or video can ever represent the sorrow that a person who was there saw and lived, like me. Those seven years of my life were the most horrible times.”

Freund said that Fordham’s College at 60 program has helped her make peace with the painful memories of her past.

“It helps me so much because when I’m in the class I don’t think of anything else,” said Freund, who has been taking classes since she retired from social work in 1977. “I concentrate only on what the professor teaches. It’s one of the things that takes me away.”

She said her secret to living as long as she has is that she doesn’t allow herself to be bitter about the things she endured during the Holocaust. Instead, she would rather share her story widely so that such mass genocide never happens again.

“It’s my sacred duty,” she said. “My greatest wish in life is that I can see peace on earth, and that people can understand each other.”

Spiegelman called the special connection he shares with Freund “a living bond” that goes beyond history. It has also helped him to honor his father’s legacy.

“Our shared experience gives voice to what my father couldn’t say,” said Spiegelman.