A new book co-edited by Fordham faculty, Christianity, Democracy and the Shadow of Constantine (Fordham University Press, 2016) examines where Catholic and Orthodox Christianities meet politics.

Among the book’s many themes are several critiques on the influence of Western liberalism in the Orthodox East. The critiques examine how some governments attempt to use that influence to divide the religions for geopolitical purposes.

Among the book’s many themes are several critiques on the influence of Western liberalism in the Orthodox East. The critiques examine how some governments attempt to use that influence to divide the religions for geopolitical purposes.

In 2013, the Orthodox Christian Studies Center sponsored a conference on the subject as part of the Patterson Triennial Conference Series, which seeks to bridge the Orthodox/Catholic divide. Many of the conference’s participants contributed to the book, which was co-edited by the center’s co-directors, Aristotle Papanikolaou, Ph.D., the Archbishop Demetrios Chair in Orthodox Theology and Culture, and George E. Demacopoulos, Ph.D., the Fr. John Meyendorff & Patterson Family Chair of Orthodox Christian Studies.

Papanikolaou said that the book, like the conference, attempted to cut through much of the “identity construction” that occurred in Eastern Europe after the collapse of communism. The new order forced traditionally Eastern Orthodox countries to grapple with the relationship between Christianity and liberal democracy. The book features essays by Catholic, Protestant, and Orthodox theologians reflecting on the post-communist Orthodox world and in Western political theology.

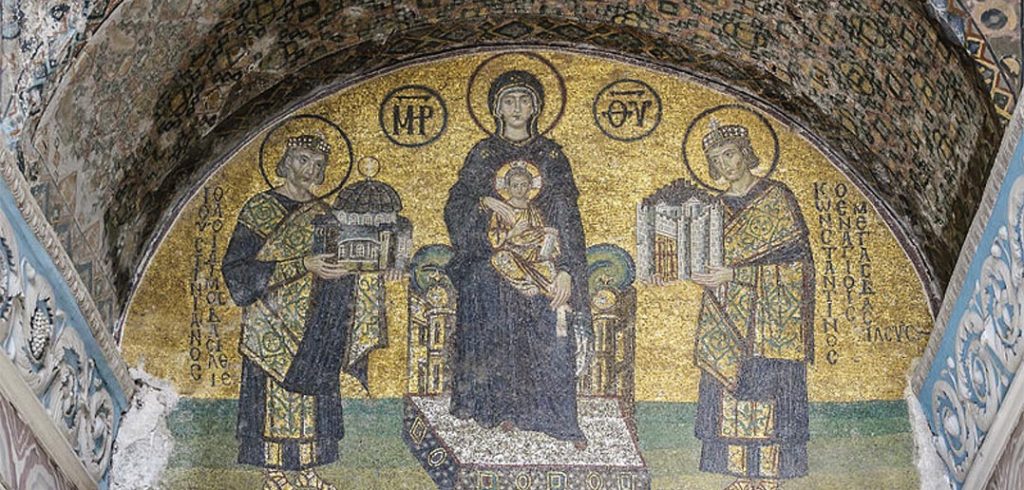

“The Christianization of the Roman Empire continues to cast its shadow over political theology,” said Demacopoulos. “It would seem that Christianity should have this easy relationship with liberalism, but it’s not that simple.”

He said that for many years ambivalence toward liberalism prevailed on the part of the Catholic and Orthodox traditions, but liberalism’s focus on the individual has its critics.

“Some of liberalism’s values are antithetical to Christian values,” he said. “The critics aren’t against democracy per se, but many believe we should keep a strong distance to certain kinds of concepts. Even though Christianity is almost seen as the source of liberalism, there seems to be a Christian backlash to something it created.”

On the Catholic front, Papanikolaou noted that Pope Francis supports democracy and isn’t looking to engage in a cultural war, but the pope also takes a critical stance toward liberalism as it relates to issues of sexual morality and neglect of the poor.

But in many Eastern countries where Orthodoxy prevails, governments that once shunned the Orthodox Church now see political opportunities to embrace the church as way to distinguish national identity. Nowhere is this more evident than in Vladimir Putin’s Russia, said Papanikolaou. So liberal values, such as same sex marriage, are seen as wedge issue opportunities.

“Putin saw this advantage to create this East/West division, and homosexuality became this global red line,” he said. “Russia is declaring that we’re not going to accept this.”

And the Russians are not alone, he said. The Orthodox Church in Romania, Bulgaria, and Greece, where the separation of the church and society is somewhat blurred, have all adopted a hard-line tone against liberalism.

“They’re following the Russian lead in calling out that Western civilization has lost its way and promotes immorality,” he said. “The governments are using traditional values as a way to carve out this difference between them and the West, and the churches are seeing it as their role too.”

He noted that there are many Catholic theologians who react strongly against what they see as an ideology of the West. And there are Orthodox theologians, like Archbishop Anastasios of Albania, who are more supportive of human rights discourse.

“The book offers conversation of all these different points of view,” said Papanikolaou. “While there are a lot of Orthodox Christians that are troubled by it, that doesn’t mean that the church should be used in the way of a political divide.”