James B. Comey, the director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation, revealed to a gathering of cyber security professionals at Fordham on Jan. 7 that newly declassified details about the bureau’s investigation of the November cyber attack that devastated Sony Pictures.

Comey said it is certain that the cyberattack was instigated by a North Korean-based group.

“There is not much in this life that I have high confidence about. I have very high confidence in this attribution, as does the entire intelligence community,” he said.

Comey first publicly laid responsibility for the hacking, which is believed to have come in response to the studio’s satirical film The Interview, on Dec. 19. He shared the new information about the attack on the second conference day of the 2015 International Conference on Cyber Security (ICCS2015), which offered three full days of conferences and talks co-hosted by Fordham and the FBI.

He told conference attendees that the “Guardians of Peace” a North Korean-based group that that was behind the hack, sent threatening e-mails to employees of Sony. Although most of the e-mails were sent via proxies that made the identities untraceable, the hackers got sloppy in some cases and revealed IP addresses that were exclusively used by North Korea.

In addition, malware used in the Sony attack bore striking similarities to a cyberattack that the North Koreans conducted in March of 2014 against South Korean banks and media outlets.

“Several times, either because they forgot or they had a technical problem, they connected directly—and we could see them,” he said. “They shut it off very quickly before they realized their mistake, but not before we saw it and knew where it was coming from.”

Comey said the FBI detected spear phishing attacks on Sony’s computer networks as recently as September, and that it seems likely to have been the method, or “vector,” of the attack.

Comey prefaced his remarks on Sony with an address about cybercrime, noting that the government’s decision to publicly name North Korea is part of a strategy to fight the biggest and baddest actors in what calls the “evil layer cake.”

Nation states sit at the top layer and are followed by terrorists, organized criminal actors, sophisticated worldwide hackers and botnets, “hack-tivists,” weirdos, bullies, pedophiles, and creeps.

Cisco has predicted that in five years, there will be 50 billion devices connected to the Internet, making protection against cybercrime more important every day. Comey said the FBI’s five-point strategy for combating it includes: Focus ourselves; Shrink the world; Impose real costs on bad actors; Improve relationships with state and local law enforcement; and Improve relationships with the private sector.

He compared the current changes in crime to the great vector change that happened in the 1920s and 1930s when automobiles and asphalt enabled criminals to move quickly, making it easy to rob banks across state lines.

“[Cybercrime] is that times a million. Dillinger or Bonnie and Clyde could not do a thousand robberies in all 50 states in the same day in their pajamas, from Belarus. That’s the challenge we face today,” he said.

—Patrick Verel

Director of National Intelligence on Sony:

“Most Serious Cyberattack Ever Made Against U.S.”

In the Day 2 opening keynote, U.S. Director of National Intelligence James R. Clapper cautioned those gathered not to underestimate North Korea’s cyber capabilities or national animosity, especially in light of the recent cyberattacks against Sony, which Clapper called “the most serious cyberattack ever made against U.S. interests.”

Clapper, who Fordham President Joseph M. McShane, S.J. said is “at the vortex of keeping things right for all of us” and who the New York Times described as “gruff, blunt-speaking… an unlikely diplomat, but perfect for the North Koreans,” offered as evidence a personal account of dealing with North Korean intelligence.

In November, Clapper traveled to the secluded country as a presidential envoy to retrieve two imprisoned Americans. Damaging their airplane’s tire while landing on a decrepit runway was only the first sign of “eerie” troubles that Clapper’s team would encounter during their two days in Pyongyang.

“From what I saw of downtown Pyongyang, I was struck by how impassive everyone was,” Clapper said. “They didn’t show emotion, didn’t stop to greet each other, didn’t nod hello, didn’t converse or laugh. They just went on about their business, almost like automatons.”

Later that night, Clapper and his team enjoyed an elaborate, 12-course dinner with the general of North Korea’s Reconnaissance General Bureau (RGB), who spent the meal railing against “American aggressors” aiding and abetting South Korea in provoking a war against the north, said Clapper.

The following morning, an emissary from the country’s state security arrived at Clapper’s hotel and informed him that North Korea no longer considered him a presidential envoy and thus could not guarantee his safety and security from the people of Pyongyang, who knew who he was and why he was there.

Four hours later, the same emissary returned and told Clapper that his team had 28 minutes to gather their luggage and check out of the hotel. From there, the team was ushered to a conference center where the two American prisoners were waiting. There, the North Korean minister of security read a proclamation from Kim Jong-un granting the prisoners amnesty.

“They were turned over to us, we got in our vehicles, and took off toward the airport,” Clapper said. “I can’t remember another time that an American airplane looked so good.”

Though not explicitly related to cyberterrorism, the incident offered important insights into North Korean hostility, Clapper said.

“The general I had dinner with is the one would have had to okay the cyberattack against Sony,” he said. “He is illustrative of the people we’re dealing with in the cyberworld. The vitriol he spewed at me over dinner was real. They really do believe they’re under siege from all directions. They paint us as an enemy about to invade their country every day… and they are deadly serious about fronts to their supreme leader, whom they consider to be a deity.”

Moreover, he added, North Korea is striving to be recognized as a world power. In the past, the country’s efforts to exert dominance involved amassing nuclear weapons. Now, it views cyberspace as the weapon of the future.

“Cyberwarfare is a powerful new realm for them, because they believe than can exert maximum influence at minimum cost,” Clapper said. “That’s why we have to push back. If there is no consequence, they will do it again and keep doing it. And others will follow suit.”

—Joanna Mercuri

Panelists Advocate for

Strong Privacy Safeguards

In the online world, security leads to privacy, obviously, but the reverse is also true: strong privacy safeguards are often the starting point for keeping cybercriminals out.

That’s according to one expert at ICCS2015 who spoke on a privacy panel moderated by Joel Reidenberg, Ph.D., professor of law and the founding director of the Fordham Center on Law & Information Policy. In the words of Princeton University professor Edward Felten, Ph.D., “many standard privacy vulnerabilities … are useful to an adversary who wants to understand who we are and what we’re doing in order to target an attack.”

For instance, before attackers can successfully infiltrate a computer system via e-mail, they first have to craft a legitimate-seeming message that is likely to be opened.

“The more the attacker knows about that individual and their life and their schedule, who their associates are … the more accurately they can target that ‘spearfishing’ email” and mount a successful attack, said Felten, Princeton’s Robert E. Kahn Professor of Computer Science and Public Affairs and director of the Center on Information Technology Policy.

Felten and two other panelists grappled with how best to ensure privacy online and protect civil liberties while also managing the huge amounts of data that institutions of all types are collecting.

Disciplined data-gathering is another important privacy measure, panelists said. Institutions sometimes feel the need to “get on the Big Data bandwagon” before figuring out what they’ll do with all the data they wind up collecting, said Cameron Kerry, senior counsel at Sidley Austin LLP and former general counsel and acting secretary of the U.S. Department of Commerce.

“A lot of that data is not useful,” he said. “Making rigorous choices is an important part of the process.”

Without good data management, Felten said, “you may have all kinds of data sets that you didn’t know you had, and you may only be reminded of them when they show up in the press.”

Panelist David Medine, chairman of the Privacy and Civil Liberties Oversight Board in Washington, D.C., noted the potentially chilling effect of this large-scale data gathering by government agencies.

“If I’m a source and I want to call a reporter and be a whistleblower against the government, and then the government now has a phone record between me and a New York Times reporter, I may be less willing to do that,” he said.

—Chris Gosier

Hickton:

Industrial Infiltrations by Chinese Hackers

Leave U.S. Companies Vulnerable

When he started an investigation into trade-secret thefts, David Hickton wasn’t expecting to find a “thirst for industrial organization data.”

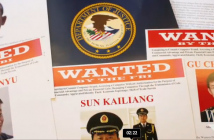

But in 2014, the U.S. district attorney for the Western District of Pennsylvania brought charges with the justice department against five Chinese Peoples Liberation Army officials for infiltrating the corporate computer systems of big-name companies—U.S. Steel, Westinghouse Electric, Alcoa, and others.

But in 2014, the U.S. district attorney for the Western District of Pennsylvania brought charges with the justice department against five Chinese Peoples Liberation Army officials for infiltrating the corporate computer systems of big-name companies—U.S. Steel, Westinghouse Electric, Alcoa, and others.

On Day 2 of ICCS 2015, Hickton gave a detailed presentation of his office’s investigation, which resulted in indictments handed down last year.

Much of the information that the Chinese were after seemed obvious, such as research and development, industry analysis, and deliberations of senior management. But some of it surprised Hickton.

“They wanted to know how often the [boards]met, what titles they had, and who reported to who,” he said. “There was also a huge interest in legal strategies.”

Hickton said the reality is that the Chinese don’t have MBA programs on a par with the United States; while they were most critically interested in product development, they also wanted to understand how American companies are run.

Joint ventures with Chinese state-owned businesses often left their American counterparts vulnerable, as was the case with U.S. Steel, he said. Just as the U.S. Steel was transforming from a “flat roll” steel company to one able to produce oil country seamless pipes that are used in fracking, the Chinese military stole proprietary design specifications of the pipes.

“U.S. Steel . . . spent a lot of money on research and design and like any company they need to make a return,” he said. “When they brought the pipe to market, the Chinese had already flooded the market with the same pipe at lower than cost.”

Normally, a complaint would be made against the Chinese hackers at the World Trade Organization. But before U.S. Steel lawyers could bring the case to the WTO, even their legal briefs were already in the possession of the Chinese.

“This is just a flavor of what was taken,” he said. “It is literally impossible to collect and report the total value of what was lost by American companies, but we know that it’s the largest wealth transfer in history.”

—Tom Stoelker

Experts Discuss Role of Language in Ferreting out Internal Threats

Some of the greatest cyberthreats to an organization actually come from within, as Chelsea Manning and Edward Snowden proved in 2010 and 2012, respectively.

At “Insider Threat,” a panel held Tuesday evening at ICCS2015, Ed Stroz, GSB ‘79, founder and co-president of Stroz Friedberg, detailed how the use of psycholinguistics, which is the study of how humans acquire, use, comprehend and produce language, can help identify employees who might commit cyber crime.

Stroz was joined by Stephen R. Rand, Ph.D., a consultant with Behavioral Intelligence Specialists, LLC; Eric Shaw, Ph.D., a Washington D.C.-based consulting psychologist; and Scott Weber, managing director, Stroz Friedberg.

Stroz said that in addition to monitoring an organization’s network for suspicious activity —for example, downloading inordinate amounts of data at odd hours—administrators can get a sense of an employee’s state of mind from the language they use. When he worked at the FBI, Stroz said it wasn’t hard to tell when someone on his team was experiencing stress in their personal lives—after all, they spent so much physical time together during a workday.

“In today’s environment, we often don’t have the same kind of personal interaction with each other, but we do get tons of communications through computers,” he said.

Moderating the panel, Stroz asked whether there was some way to “bring about that same sort kind of care that you would have with your co-workers” back when you were sitting next to them.

Shaw said he once helped a client sift through 10,000 e-mails that had been sent to prohibited countries, and isolated three concepts in particular within the language that indicated a potential violator. They are negative sentiment, feeling victimized, and having someone to blame.

Panelists said that a key blind spot for employers is “maladaptive organization response,” which occurs when an organization realizes an employee has engaged in improper behavior and moves to terminate them. Shaw noted that 80 percent of people who used computers to sabotage a company or steal from it did so after they’d been fired.

“The first thing we have to do in a lot of situations is convince corporate leaders and government sponsors to keep their friends close, but [keep]their enemies closer in some way, he said.

—Patrick Verel