It’s a time honored maxim that those who do not learn from the past are doomed to repeat it in the future.

For Lise Schreier, Ph.D., there is much to be learned from an especially heinous practice that thrived in Europe from the mid-15th century to the early 19th century: child-gifting, the act of bringing dark-skinned children from Ghana, Senegal, and India to Europe, and offering them as presents to high society women.

In “Toying with Blackness,” a talk she presented on Jan. 19 at Fordham Law’s Center on Race, Law & Justice, Schreier, an associate professor of French, shared some of the research that she’s been conducting as part of a National Endowment for the Humanities grant toward publication of a book, Playthings of Empire: Child-Gifting and the Politics of French Femininity.

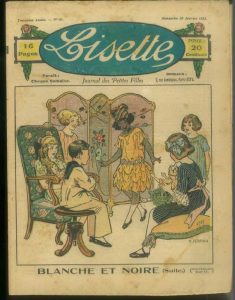

Among the more baffling yet illuminating aspects of this practice, she said, was the way it was used as a teaching tool for French children, even after the practice was discontinued. In the final chapter of Playthings, Schreier details how the Nov. 19, 1922 edition of the widely read Lisette, Journal des Petites Filles (Lisette, A Magazine for Young Girls), debuted a serialized comic titled Blanche et Noire (White and Black).In the story, a black girl named Raïssa is “rescued” from a black abuser and given to a white French girl named Mady. Raïssa is portrayed as grateful for being rescued from her abuser, and Mady is thrilled to have a new “toy.”

“But the story doesn’t end here, because as you know, there is no such thing as a free gift. In exchange for her new plaything, the French girl is expected to behave in very specific ways. More to the point, the black ‘toy’ is what turns her into a proper, obedient French citizen,” Schreier said.

One of the things Schreier finds interesting here is the fact that Mady was not the only little girl to get a gift. Her young readers also got a gift: the magazine itself.

“We all know how it works: if you behave, you get a toy. If you don’t, no present for you. It’s important to realize that the story of the black child being gifted to the white child was itself a present to good little French girls.”

One baffling aspect of Blanche et Noire was that it was ostensibly set in the 1920s, even though slavery was abolished in France by then, said Schreier. And Saint-Domingue, where Raïssa was supposed to come from, had become independent and was already renamed Haiti by then. Schreier said this deliberate amnesia about the past is further proof that blacks’ lives didn’t really matter in France—even in the early 20th century.

“The idea that you can have a fictional character [in the 1920s]and decide that she’s a slave, and then have another character buy her and offer her as a toy, is depicted as completely normal,” she said.

“Add the fact that the black character is not only an object but is also ahistorical. That tells us a lot about the ways in which blacks were objectified at various levels and for a very specific purpose, which is educating French girls.”

Little of this history is known in the United States, Schreier said. The conversation among attendees following her Jan. 19 presentation therefore focused on the different ways in which slavery was practiced on the two continents. As such, the images from Lisette are often unsettling to American audiences.

“When you talk about children’s literature—which is connected with tenderness, presents, family, and domesticity—you don’t necessarily think about racial subjection.

“And yet these are very powerful hidden mechanisms,” she said, “so it’s even more important to understand them.”